No leftover $ for food: Almost half of all US college students are food insecure

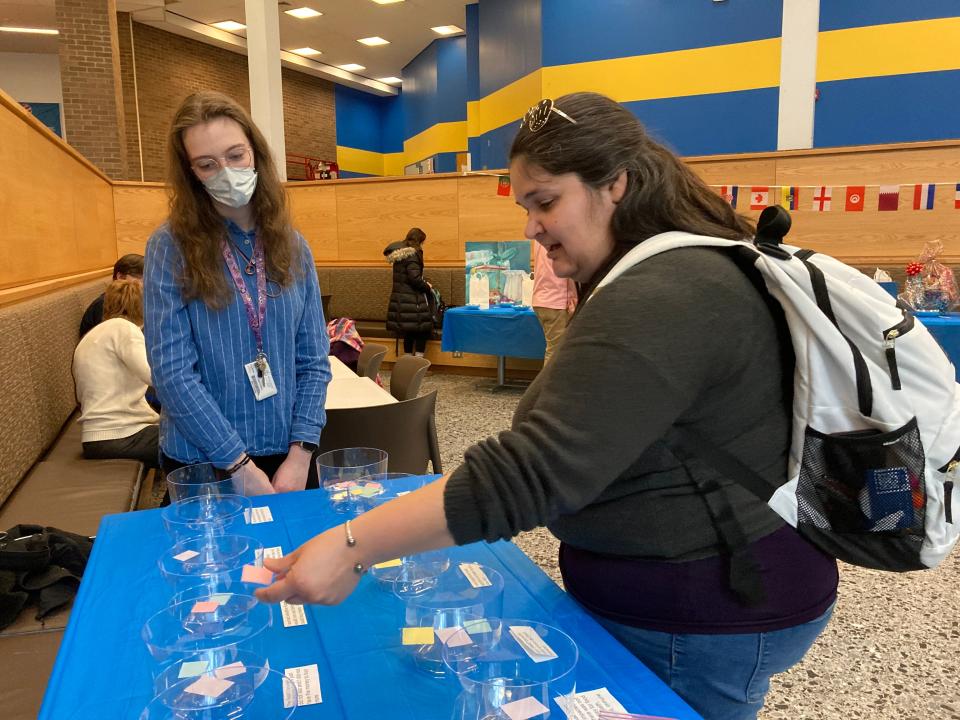

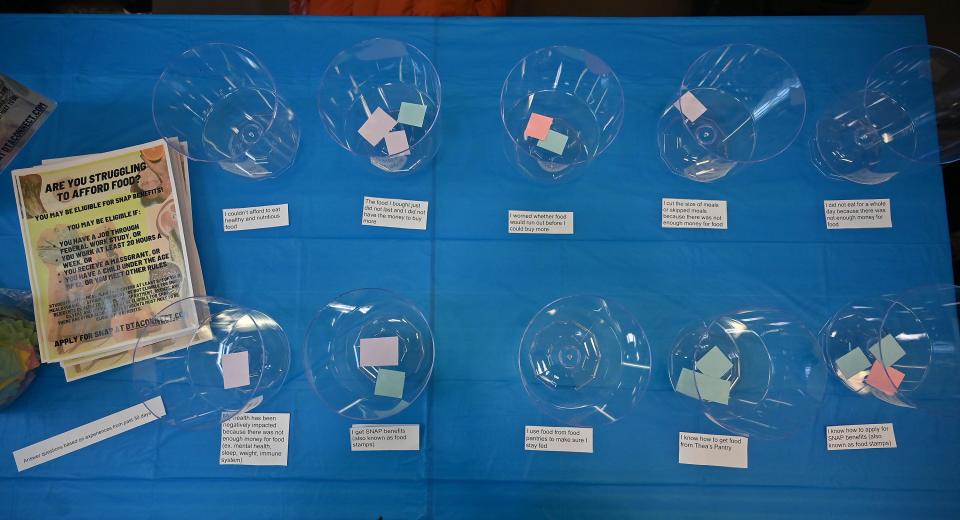

With three children still at home, Worcester State University liberal arts student Greter Barcelo, 43, said she worries about food — not constantly as in all the time, but enough to prompt her to stop at a food insecurity survey table at the university’s annual “Empty Bowls” fundraiser Wednesday to discuss completing her application for Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP) with a volunteer.

Barcelo, who makes ends meet while studying for a degree by working as a substitute ESOL (English for speakers of other languages) teacher, said the money she earns is not enough, “but I’m making do.”

She said she's eager to graduate and find a full-time job that offers health insurance where financial worries do not include finding funds to feed her children.

The SNAP gap: Many eligible students fail to apply

The fundraiser where she discussed the SNAP application with junior urban studies major Zadia Valenze, a student in the Urban Action Institute, was organized to support Thea’s Pantry, the campus food pantry.

“We’ve been involved with the Hunger Free Campus Coalition since 2019,” said Adam Saltsman, an assistant urban studies professor and director of the Institute. “We hope to get this legislation passed in Massachusetts this year.”

The initiative has been passed by six other states: California, New Jersey, Maryland, Minnesota, Louisiana and Pennsylvania.

Massachusetts legislators have put forth companion bills in the Senate and House that would establish a money pool accessible by the state’s public universities, colleges and community colleges to fund initiatives to address the problem of hunger on campus.

College surveys dating from 2008 revealed food insecurity on campus

The growing pervasiveness of food insecurity on the country’s college campuses, as revealed by numerous surveys of college students conducted regularly since 2008, surprised even the researchers conducting the surveys.

In its 2016 report, the HOPE Center for College, Community and Justice at Temple University revealed its surprise at certain responses while asking college students in Wisconsin: How is college going? In the report researchers indicated they expected to learn students were stressed by financial issues of paying tuition and purchasing books.

“But a few surprised us, speaking instead of difficulty finding food, even being distracted from classes by persistent hunger,” a sentence included in the report’s preface. Since that revelation, the HOPE Center has incorporated questions of food security into its annual survey.

College students are hungry — and not by choice

The results from the 2016 survey found of 3,800 students at 34 two- and four-year institutions in 12 states, one in five students (about 22%) reported differing levels of food insecurity. As many as 49% of students reported being hungry in the last 30 days.

Numbers differed at the different institutions, with more students at community colleges reporting insecurities as compared to students attending four-year institutions. Differences were attributed to the composition of the student body, with the influx of more nontraditional students: low-income, first generation college students and more students of color attending two-year institutions.

And 13% attending community colleges also reported being homeless. Most were working, receiving financial aid and many were on meal plans. While less prevalent on some four-year campuses, students attending there face hunger in between semesters and whenever dorms and dining halls are shuttered. Housing insecure students face both hunger and homelessness.

The numbers from the survey released in 2021, jumped: three of every five students reported basic insecurities with food and housing insecurity at the forefront.

“We’ve done our research,” Saltsman said, explaining that the school has linked food insecurity to academic performance.

WSU links GPA to food security

The level of food insecurity, he said, is tied to a student’s GPA; well-fed students earn better grades.

At Worcester State, one-third of enrolled students report some level of food insecurity and many are students who identify as of color or Latinx, said Saltsman.

Schools around the country have been stepping up in the last decade to address students’ basic needs. Many institutions in Massachusetts have created food pantries students can access without income eligibility requirements. They have banded together to create meal plan point banks; (Swipe it Forward) students with an overage of points can donate to the bank to feed those without any points.

A consortium of student leaders at both private and public universities in the greater Boston metropolitan area are urging the state legislators to pass the Hunger Free Campus Act. They have also endorsed the companion bills filed by legislators.

Administrators at Clark University have recognized that food insecurity is a critical basic needs issue that must be addressed. Students there have coordinated and have been running a food pantry to serve Clark students.

“The issue of food insecurity was brought to our attention through our student advocacy, specifically the student organization Food Insecurity Resistance Movement (FIRM),” said Kamala C. Kiem, associate provost for student success and dean of students in Clark’s division of student success. “President David Fithian recognized the important work of FIRM and the needs of our students and provided substantial funding for the food pantry this year.”

The university, through the Food Security Taskforce (which includes FIRM representatives) under Domenica Perrone's leadership, is working to address food insecurity, Kiem said, adding the institution will be releasing a request for proposal to have a community partner manage the food pantry. Clark has a “Swipe Out Hunger” program, and an emergency fund for students. Other campus organizations, like Clark’s Hillel, also work to address food insecurity in the community.

Advocating SNAP signups, creating dining hall 'swipe' banks

Massachusetts’ many college campuses, both public and private, have also created action teams to reach out to students to help them apply for SNAP benefits, find shelter alternatives and address other basic services. Worcester State works with Quinsigamond Community College and offers dorm rooms for unhoused students attending the neighboring two-year institution.

That community college started addressing basic needs for students in 2017, with the release of the HOPE Center report.

Of the 7,000 students enrolled at Quinsigamond, some 49% reported food insecurity, said Theresa Vecchio, the college’s dean of students. Those figures were compiled before the pandemic. Since then, student needs have risen exponentially.

The pantry, The Home Plate, started small: A few shelves holding nonperishable food and $2,000 a week in groceries purchased retail at local food stores, Vecchio said.

Since then the Quinsigamond College food bank has grown to an 800-square-foot space with a restaurant style, three-door freezer, a sophisticated refrigeration system and Goya Foods donating to The Home Plate regularly. In 2020, the organization was certified by the Worcester County Food Bank as a partner and now accepts 2,000 pounds of food a week from the antihunger organization.

The partnership between the college and the food bank took some time to develop; the food bank’s philosophy embraced distributing food to all visitors. Quinsigamond is focused on feeding its students; 250 had signed up for the pantry by the end of the first summer of operation.

“Every student signed up for the program is feeding four or five people at home with the food we supply,” Vecchio said, explaining that the reach of its food to other community members was a key factor in its partnership with the county foodbank.

The college recently invested in a refrigerated locker system, similar to the food-service lockers used by an online commercial grocery store. Students in the program log in online, select up to 20 food items a week and retrieve them from the refrigerated lockers at times that are convenient for them. The college also purchased a refrigerated truck for both pickup of donations as well as deliveries.

Access to nutrition improves graduation, retention rates

In researching the effectiveness of its response, Quinsigamond surveyed the students who reported food insecurity: Of the 346 students who accessed The Home Plate in the spring of 2022, 279 completed their degree or enrolled in fall semester classes.

“We kept a significant number of students on campus to complete their degrees or re-enroll in more classes,” Vecchio said.

In discussing the history of the Quinsigamond food bank, Vecchio praised the school’s role model: Bunker Hill Community College in Boston.

That food bank, opened in the fall of 2019 was the first in the nation to incorporate cooler lockers as a means of delivering food to students.

“Initially, we had a walk-in service; students would log in, pick choices online then come in to pick up their items,” said Molly Hansen, coordinator of the pantry, The DISH (Delivering Information, Sustenance & Health).

Since then, at least eight other schools have installed the lockers, Hansen said, adding, “We’re trend setters.”

The college plans to install additional lockers on its Chelsea campus in March.

“They can pick up their food at any time; it’s super easy, super convenient,” Hansen said.

The community college participates in the Obama-era advocacy group Achieving the Dream and has incorporated its student-first, student-centric focus, said Brendan Hughes, college spokesperson.

“We were one of the first to align with the program and we operate around addressing student needs,” Hughes said.

Addressing basic needs including food, shelter and transportation is tantamount and offered in a central location, he said.

“We don’t want students going ‘door-to-door’ looking to get their needs met," he added.

But supplying hungry students with nutritional food is just the tip of the iceberg.

“It’s a Band-aid,” said Kathleen O’Neill, director of the college’s Single Stop program. Efforts to inform college students of their eligibility to receive SNAP benefits and other aid can meet with resistance. “Our biggest barrier is the stigma around applying for benefits. I tell the students that SNAP is a food scholarship, just like a Pell Grant, but for food.”

Colleges and universities, she believes, must make transformational changes and focus on addressing the whole student and availability of services must be sustainable.

Legislative response to collegiate food insecurity

That’s where the state comes in with bills sponsored by Sen. Joan Lovely, D-Salem, Rep. Andres Vargas, D-Haverhill, and Mindy Domb, D-Amherst. The proposed legislation is co-sponsored by several members of Worcester’s delegation including Sens. Michael Moore, D-Millbury, Robyn Kennedy, D-Worcester, and John Cronin, D-Lunenburg; as well as Reps. David H.A. LeBoeuf, D-Worcester, and Natalie Higgins, D-Leominster.

The bill, said Moore, would fund the creation of a central office, a resource available to all of the state’s public two- and four-year campuses, that would administer funds to develop technology and identify grant opportunities for addressing hunger on campus.

“It’s similar to what we are looking at in K to 12th,” Moore said. “Students going to school need to concentrate in their curriculums, their majors and on attaining (the) skills (they are attending school to learn) and should not be worried about finding a meal.”

The bills are two of some 7,000 filed in this legislative session, Moore said. However he would like to see them in place as soon as possible.

In a written statement, Lovely said she is, "proud to be the lead Senate sponsor of legislation to create a Hunger Free Campus Initiative. Many students enrolled in higher education programs face food insecurity with the high cost of living, recent inflation, and rising tuition expenses."

In her district, Salem State University and North Shore Community College have established food pantries and mobile markets on campus to help alleviate food insecurity.

"I filed this bill to provide students with support to lead healthy, productive lives inside and outside of the classroom," Lovely said. "We must continue to work together to end campus hunger across our commonwealth.”

The pervasive myth of the “starving college student” surviving on ramen should be retired; today’s “starving” college students facing food insecurity are literally starving.

This article originally appeared on Telegram & Gazette: Massachusetts college students increasingly face food, housing insecurity