No matter your politics, you gotta wonder: Why is Michigan No. 1 in recalls?

Even veteran politicians and tenured professors of government are surprised to learn this about politics in Michigan:

The state is a recall leader. It often tops or almost tops all states in "recalls filed." That's the first step in starting a recall. Somebody files a petition, gets publicity, and gives instant headaches to a political target. According to the political data site Ballotpedia, Michigan had the most recalls filed last year; and the most again this year, through October, and Michigan is so far ahead of No. 2, California, that at year's end the Great Lake State is sure to have the most, a Ballotpedia researcher said. In other recent years, Michigan has been either second or third in number of recalls filed.

But Michigan also is a leader in failed recalls. They die on the vine, as winemakers say. This year through October, 126 elected officials were targeted; only about 6% were ousted. Many of Michigan's recalls never get on ballots because volunteers can't collect enough signatures in the 60 days allowed. Many who've tried say they realize that only well-funded campaigns that hire professionals, called circulators, can gather the number of signatures required by law: 25% of the votes cast in the target individual's district for all candidates who ran for governor in the last election for that office. At a recent recall attempt in Troy, that translated to around 11,000 signatures. The potential tab? The cost of collecting signatures reached $20 apiece last year, according to Ferndale-based First Choice Contracting LLC — cited in Bridge magazine..

Most Michigan recall wins are obscure. Of the 6% of officials who were recalled this year, most were trustees of sparsely populated townships, in rural areas of the state. In such areas, it sometimes takes just a few impassioned voters to gather enough signatures. Then, the same crowd can enlist friends and family members to vote in a special election. The result? Sometimes they do, actually, manage to recall a township trustee or supervisor. In more populous areas, very few recalls succeed.

What's going on? Michiganders see a torrent of recalls get started, then a flood of failures. "It's pretty stunning to see this in Michigan," said Dave Dulio, a professor of political science at Oakland University. Dulio, an expert on local politics nationwide, said he could find no obvious explanation.

"Are we so polarized? Other states are, too, so that's not it," he said.

"It's weird and it's wasteful," lamented Oakland County Commissioner Dave Woodward of Royal Oak, former chair of the Democratic Party in Oakland County. In full agreement with Woodward's sentiment is a recent recall targets, state Rep. Sharon MacDonell, of Troy.

MacDonell, a Democrat, said she was dismayed when Republican activists launched a fall campaign against her, complete with "personal attacks." They set up tables outside the city hall, the library, and other spots in Troy, apparently ignoring MacDonell's political history. She'd cruised to victory in 2022, winning with 58% of the vote against 42% for her opponent. Still, a band of about 30 volunteers thought they could undo that history. MacDonell, elected to her first two-year term last fall, took office on Jan. 1 in the 56th House District, which represents all or parts of Troy, Clawson, Royal Oak, Birmingham, and Bloomfield Township.

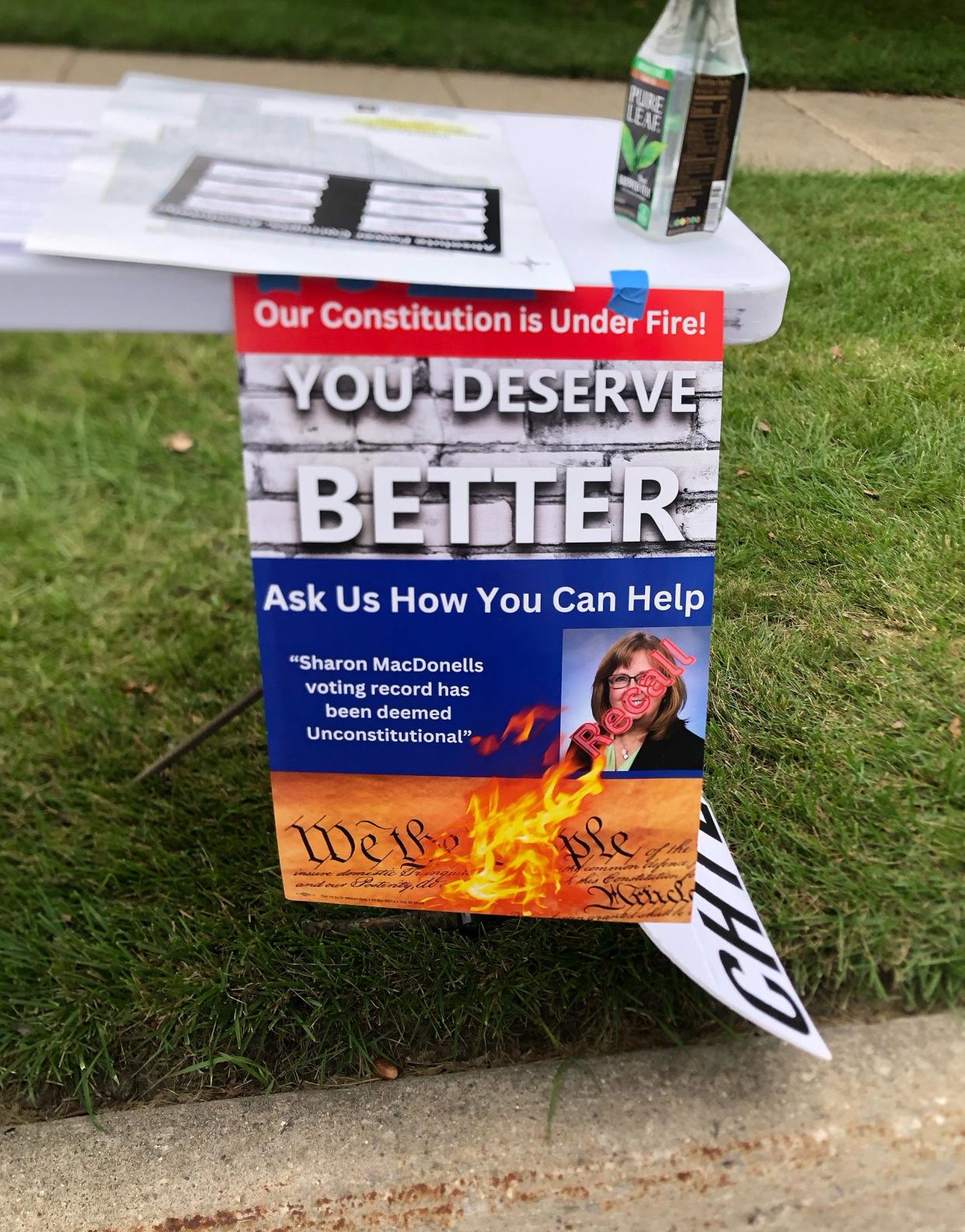

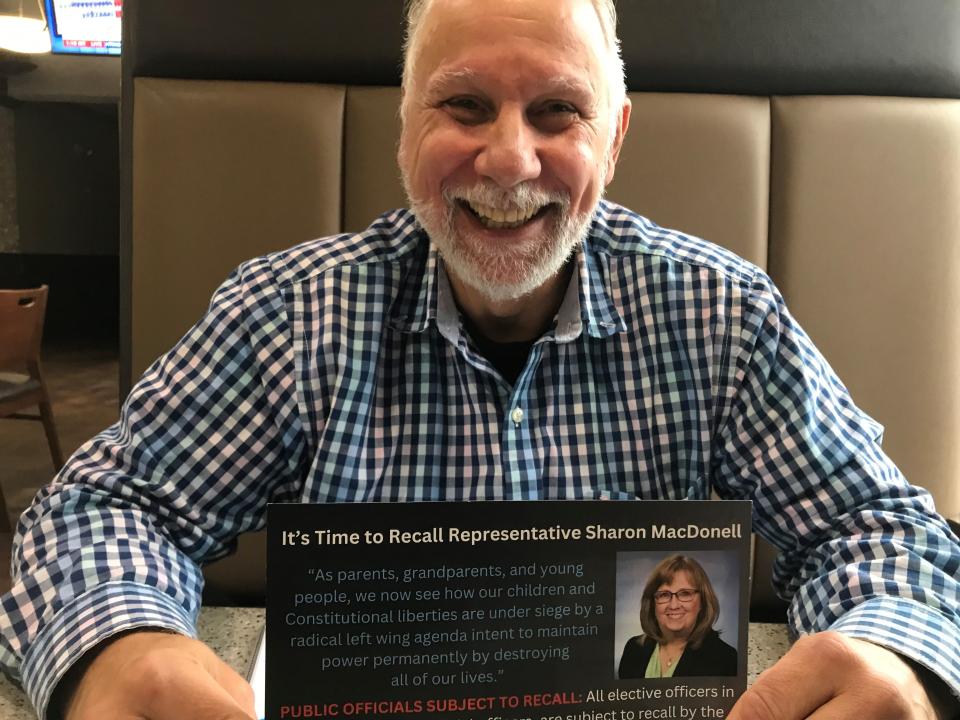

A retired physician began the recall as the official petitioner. Dr. Michael Ross pulled no punches on his recall flyers. They stated: "It's time to Recall Representative Sharon MacDonell. As parents, grandparents, and young people, we now see how our children and Constitutional liberties are under siege by a radical left-wing agenda intent to maintain power permanently by destroying all of our lives."

The recall petitions said MacDonell should be recalled because she "voted 'yes' in May on House Bill 4145 creating the Extreme Risk Protection Order Act, i.e. 'red flag' law." That referred to a Michigan's gun-control law signed by Gov. Gretchen Whitmer that same month and aimed at keeping firearms out of the hands of at-risk individuals.

The bill was prompted by shootings at Michigan State University in February. More versions of red flag laws passed the House last week by a vote of 58-52, with all Democrats joined by two Republicans, including Tom Kuhn, also of Troy. This second round of red flag laws brings Michigan "in line with 33 other states and the federal government by preventing all persons convicted of domestic violence from purchasing or possessing firearms," during their sentence and for eight years afterward, according to a news release from the group End Gun Violence Michigan, which is based at the Episcopal Diocese of Michigan headquarters in Detroit. The new laws have broad support among Michiganders, according to polls. Support gained urgency after a mentally ill man fatally shot 18 people last month before ending his own life near Lewiston, Maine, where the state legislature previously voted down red flag proposals.

Yet, Ross said his actual concern with MacDonell wasn't about guns. It was about "family values." MacDonell wasn't sufficiently pro-family and pro-marriage, he said. A devout Roman Catholic, Ross said he published a paper favoring the repeal of Michigan's no-fault divorce law, which lets couples divorce without assigning blame in court. Every state allows some version of no-fault divorce. That makes it too easy for couples to break up, Ross said. He founded a nonprofit group to promote marriage, called Defending Our Father's House.

"I wanted to educate Sharon MacDonell on that, but she wanted nothing to do with it. Marriage is really my No. 1 issue," he said. Still, Ross decided to recall MacDonell over gun control.

"I put that on there because people get more excited about guns. Conservatives do not want to be disarmed," Ross said. He declined to say how many signatures the campaign against MacDonell had collected. Nor would he say how much money the effort cost before he pulled the plug in mid-October. He asked a reporter not to write about his marital status. A spokeswoman for Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson, in charge of elections, said the recall group had not filed paperwork listing its finances.

Adding to the mixed message behind this recall attempt was the push for it from Republican operatives in Macomb County, none of whom could vote in Troy nor sign the petitions. A video produced last summer, still online, portrays recalls as a smart strategy for Republicans keen to undo the slim Democratic majority in the Michigan House. That video beckoned Republicans to join an effort to unseat MacDonell, calling them to a meeting of volunteers at the offices of the Macomb County Republican Party in Clinton Township. It pictured an unflattering photo of Gov. Whitmer over a background of red dotted with yellow stars, resembling the Communist flag of China. Then it showed MacDonell's face as the narrator urged viewers to volunteer: "We need all hands on deck!" Finally, it flashed the address of the Republican offices, next to a logo showing the GOP elephant inside an outline of Macomb County.

Mark Forton, chair of the Macomb County Republican Party, said he was unaware of the video and said the meeting "was not an official Macomb County event." But he also said he favored "the recall of all crummy legislators," including MacDonell.

"I'm sure that a number of our people were drawn to this," he said. Another Republican leader, Don Brown of Washington Township, said he viewed recalls differently. Brown is chair of the Macomb County Board of Commissioners.

"That's not my style," he said. "I personally believe we have elections every two years" for state representatives, "and that's the time for people to express their opinions. Recalls are expensive and you should only do it as a last resort," Brown said. MacDonell was one of five House Democrats and one House Republican who were announced as recall targets in July.

The ill-fated effort in Troy to unseat a popular incumbent raises questions. Michigan’s recall statute seems to serve no one well — not activists from either party, not voters and not politicians. It may be too easy to start an ill-advised recall, yet too hard to make a legitimate one succeed, said John Kulesz, a Troy resident and lawyer with firsthand experience at leading a recall in 2012.

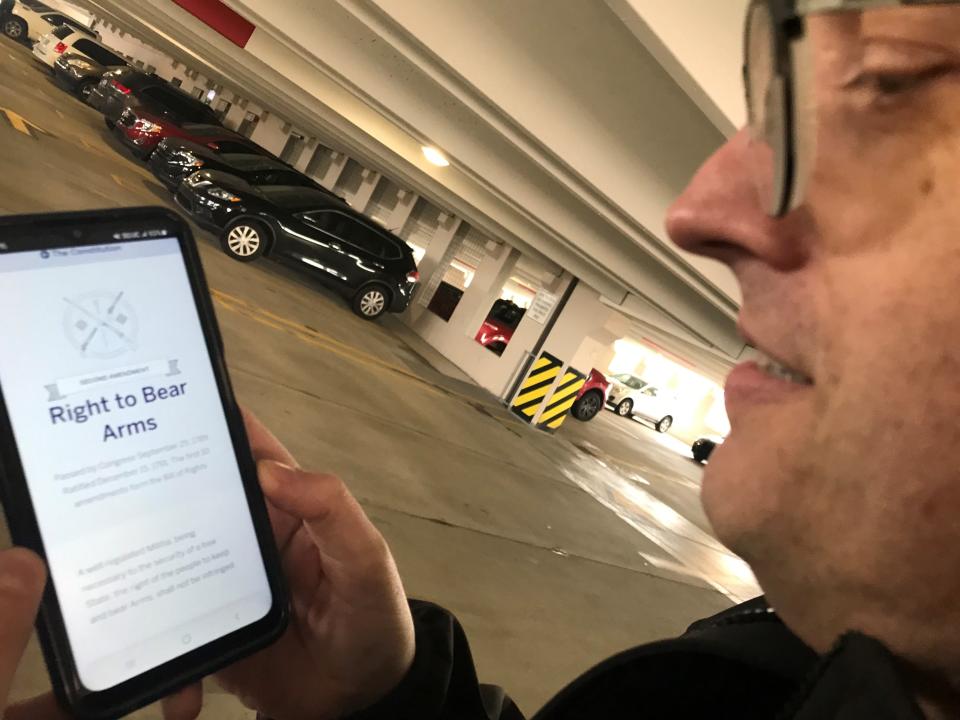

Kulesz said he got a laugh out of meeting a volunteer seeking signatures to recall MacDonell. Kulesz was entering the Troy Post Office when a circulator asked him to sign. The man, who said he was from Clinton Township, delivered a spiel about the evils of red flag laws. In doing so, he misquoted the Second Amendment wording on the right to bear arms. Kulesz, who has two apps of the U.S. Constitution on his cellphone, said he immediately set the fellow straight.

"I pulled my phone right out and showed him the correct wording. He said, 'I guess you're not going to sign,' and I said 'You're right. Not going to sign,' " Kulesz said with a chuckle.

In 2012, Kulesz was co-director of the successful recall of Troy's tea party mayor, Janice Daniels. He believes the success in that effort was a big part of why Republican lawmakers in Lansing acted that year to make Michigan recalls harder to achieve. Seeing Daniels ousted put fear into them, Kulesz said. Just one month after the election in Troy, the state House and Senate changed Michigan's recall statute.

"The right to a recall is enshrined in the Michigan Constitution," Kulesz said. Nevertheless, state lawmakers get to decide how recalls work. In 2012 they were worried. Besides the survival instinct triggered when Daniels was broomed, GOP lawmakers were said to worry about possible backlash after they acted to keep unions from counting as members all workers in a bargaining unit. Their change, called "right-to-work," let workers opt out of joining a union. That upset organized labor and likely contributed to the Republicans' fear. Whatever their reasons, the House and Senate majorities quickly acted to make recalls more difficult. Instead of the 90 days that Troy's volunteers had for gathering signatures to recall Daniels, lawmakers shrunk the window to 60 days.

They also added another complication. No more could petitioners simply recall an official in an election, then fill the vacancy afterward in whatever way local rules allowed. The revised law does continue to put the incumbent's name on recall ballots. But with it must also be one or more opposition candidates, running against the recall target. That can mean the opposition party must hold a primary election to choose who will face the incumbent. It can also mean there can be any number of candidates who decide to run, potentially splitting the opposition's vote.

All of this makes it harder to unseat a recall target. In one California recall election, aimed at unseating the governor, more than 100 challengers had their names on the ballot, splitting the opposition and keeping the incumbent securely in office, a spokeswoman for Ballotpedia said. Ballotopedia's data collection on recalls began in 2015, which is too recent to show whether Michigan's volume of recall attempts began climbing after lawmakers changed the recall law in 2012.

These days, Michigan's recall law seems to attract extremists who are passionate about political views but out of touch with many voters, Kulesz said. Such petitioners may be quick to file a recall attempt, but they're often short on funding and organizational skills. And they may target elected officials who aren't vulnerable. Still, even in failure, they stir up political mud. They distract officeholders from governing, forcing them to spend time and money on campaigning in midterm.

MacDonell said she worried that the recall effort against her, although never a real threat, could become "part of a statewide effort of pro-gun people." She also said she was shocked that the recall had organizers and volunteers from Macomb County, trying to influence the will of Troy's voters.

After the Free Press learned that the recall volunteers who targeted MacDonell had given up, a reporter informed her. She said she was relieved.

The recall effort "was a difficult time," especially when the circulators displayed big signs at a summer festival called Troy Family Daze, saying MacDonell "was against families and against children," said the wife and mother of two.

Looking ahead, she said, "I'm happy to move on and get back to my job."

Contact Bill Laytner: blaitner@freepress.com

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Republican activist in Troy admits he misrepresented recall he began