The Fed's rate hikes have yet to dent inflation — are Powell's 'forceful and rapid steps' really working? And are they even necessary?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The Federal Reserve’s third straight interest rate hike of three-quarters of a point is a telltale sign that the fight against inflation isn’t likely to end anytime soon.

On Wednesday, Fed officials unanimously voted for the supersized hike, the fifth this year, as previous increases have yet to put a meaningful dent in the hottest inflation in decades. The central bank’s latest move brings its new target to between 3.0% and 3.25%.

Don't miss

Mitt Romney says a billionaire tax will trigger demand for these two physical assets

You could be the landlord of Walmart, Whole Foods and Kroger

How to turn spare change into a diversified portfolio

Boomer's remorse: 5 big purchases you’ll probably regret in retirement

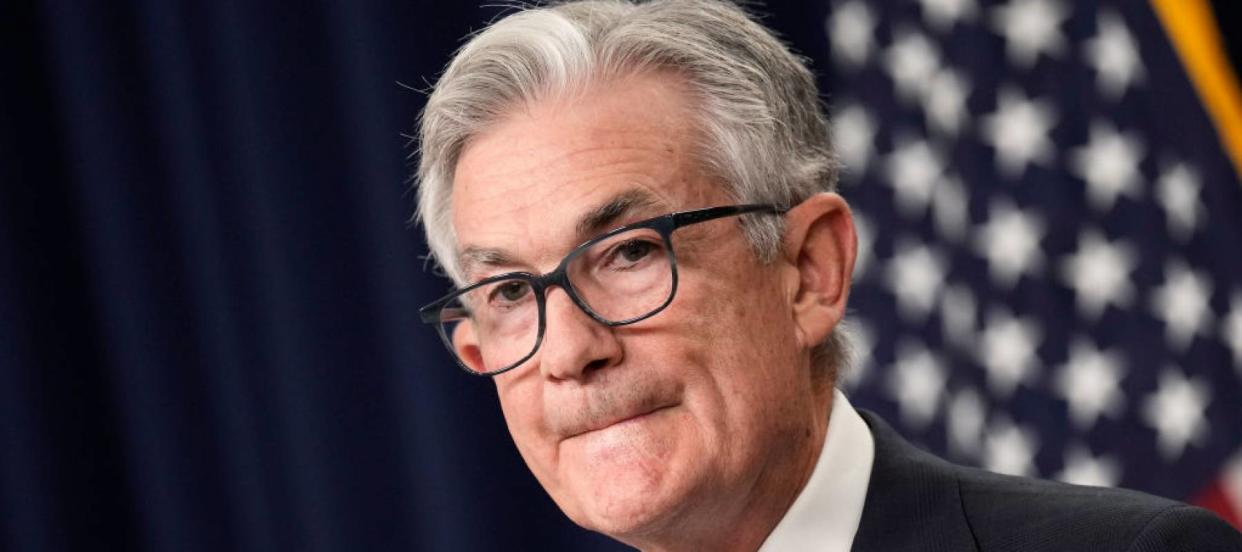

Chairman Jerome Powell, who recently warned Americans of more pain to come as the central bank works to get the economy back in balance, said the rate increases are expected to continue and be higher than previously projected.

“We are taking forceful and rapid steps to moderate demand so that it comes into better alignment with supply,” he said at a press conference.

But as rising rates and inflation persist, is the aggressive path Powell is taking leading the country in the right direction?

Why the Fed is acting so aggressively

While raising the trend-setting interest rate makes borrowing more expensive for consumers and businesses, it’s the Fed’s primary tool of cooling the economy and bringing down consumer prices that have been eating away at household budgets.

“My colleagues and I are acutely aware that high inflation imposes significant hardship as it erodes purchasing power, especially for those least able to meet the higher cost of essentials, like food, housing and transportation,” Powell said.

Last year, amid supply-chain disruptions and a boost in consumer stimulus spending, policymakers were betting that the rising prices would be short-lived given the unprecedented nature of the pandemic and the government’s response to it. Even as inflation started heating up, the Fed kept rates near zero.

But when it became clear that prices weren’t abating, Powell acknowledged that inflation might not be as “transitory” as he and his fellow policymakers had hoped.

Over the summer, inflation hit a 40-year high — and the latest Consumer Price Index (CPI) — a widely followed measure of inflation — came in hotter than expected.

Powell on Wednesday said policymakers anticipate pushing the Fed rate to 4.4% by the end of the year and 4.6% by the end of 2023. Rates would start declining in 2024, falling to 2.9% at the end of 2025, according to estimates.

Where the rate hikes are being felt the most

Since the Fed began raising rates earlier this year, borrowing costs have spiked across a host of loan types.

Mortgage rates, which aren’t directly tied to the Fed’s rate but are swayed by it, are over twice what they were last year.

“In a month or two, you’ll see people having a harder time getting that mortgage at the rate that they want or the monthly payment they were targeting,” says Michele Raneri, vice president of financial services research and consulting for TransUnion, a consumer credit reporting agency.

Interest rates on credit cards are climbing too. The rate consumers pay on plastic (and adjustable-rate mortgages) is tied to the prime rate. When the Federal funds rate changes, the prime typically follows.

The average credit card interest rate is 18.16%, according to the latest update from CreditCards.com, just off its record high. It’s up nearly two percentage points over last year.

Should the Fed have regrets?

Ken Johnson, an associate dean and professor of finance at Florida Atlantic University, has been expecting the Fed to continue on its aggressive path of rate increases.

While some market watchers thought the central bank might raise rates a full percentage point this week, Johnson says the Fed isn't taking a “rip the Band-Aid off” approach.

“Seventy-five basis points is pulling it off slowly at this point in time — but that’s better for the market,” he says.

The bank has been in a difficult spot as it tries to accomplish its so-called dual mandate, which aims for full employment — meaning whoever wants a job can find one — and stable prices with inflation at around 2% without causing a recession or massive job losses.

But thus far, the Fed’s actions haven’t been unreasonable given there “isn’t necessarily a playbook on how to respond,” Johnson said.

“In a bit of defense to the chairman and the Fed in general, what we did was unprecedented,” Johnson says, referring to keeping interest rates low in the depths of the pandemic to help shock the economy. “But I’m pretty sure Chairman Powell looks back and regrets talking about transitory inflation.”

An optimistic eye

But as to whether the Fed’s strategy is working, inflation might not be as entrenched as some fear, says James Knightley, chief international economist of ING.

One reason for that is the share of companies planning to raise prices in the coming months fell to 32% in August from 51% in May, Knightley says, citing data from the National Federation of Independent Businesses.

“This is a sizable turn which, given the strong relationship over the past 40-plus years, offers a signal that inflation rates could soon start to slow,” Knightley writes.

ING, which was calling for a half-percentage-point increase in November, believes a three-quarter-point hike is more likely. And in December, its one-quarter point projection could easily become a half-point.

What to read next

High prices, rising interest rates, a volatile stock market — why you need a financial advisor as a recession looms

If you owe $25K+ in student loans, there are ways to pay them off faster

With interest rates rising, now might be the time to finally tap into your home equity for cash

This article provides information only and should not be construed as advice. It is provided without warranty of any kind.