Noise from a firing range is driving neighbors crazy. Police say they have no money to fix it.

"Most people start their day with a cup of coffee," said Patricia Schoeninger. "I start my day hearing gunfire."

Schoeninger, explaining her dilemma to a Providence Journal reporter over the phone this month, doesn't live in a war zone. She lives in Cranston's Stone Hill neighborhood. But Schoeninger is only a third of a mile from the Cranston Police Training Complex, which houses a firing range used for weapons training and certification. The site has been there since 1952, when the department had fewer than 100 sworn officers.

To say the complex was modest back then would be an understatement. A one-story structure that once housed a flower shop was repurposed as a classroom. Black-and-white photos show shattered rock towering behind targets, a reminder of the land's past as a quarry. In the distance, nothing more is visible, aside from a heap of dirt.

In those days, according to the city's police chief, Col. Michael Winquist, officers probably would have been firing pistols, shotguns and "Tommy guns."

'We had no idea they were gonna grow'

Today, things are different. The modest structure is no more. Two training buildings have taken its place, there are 141 police officers in the department, and they fire pistols, AR-15s, specialty gas guns and less-lethal munitions.

"We had no idea they were gonna grow ... You can almost see them," said Schoeninger's husband, Al.

For a while, police departments outside Cranston, even federal law-enforcement agencies, also used the range, which meant many more rounds being fired than in the range's more modest days.

"The volume just became much more than it was in the past," Winquist said. "So the first thing I did was I sent letters to all police departments that we would no longer allow rifle fire from other departments."

That was a few years ago. Now, only two or three departments outside Cranston use the facility for handgun qualifications, the feds are gone, and for the first time this year, the Municipal Police Academy is no longer training there. Instead, it will train at the State Police Academy range in Foster.

Yet a few neighbors are still vocal, and still upset.

A band of locals, and years of criticism

"It appears to be a limited number of residents," Winquist said of the opposition. "One in particular that is dead-set against the range and wants to shut the range down."

The Schoeningers' neighbor, Martha DiMeo, has appeared with them in a handful of news articles since 2021. The trio are staunch critics who have spoken out time and again about noise from the range.

In February, their plight made it to the State House. That month, Rep. Brandon Potter introduced a bill to ban outdoor ranges within a mile of a school. The police range is near two schools – Cranston High School West and Western Hills Middle School – thus the bill would have shut it down.

But it failed.

So did Cranston's bid to enclose the range to appease neighbors. Winquist asked the state for $1.6 million of its share of federal COVID-19 relief funds but was denied. Had police been given the funding, they could have transformed the site into an indoor range and contained nearly all of the sound.

At this point, the city is running out of options. Police must be recertified each year on pistols and rifles, making the training essential, yet locals are troubled by the sound, and there isn't money to do much about it.

Mayor Ken Hopkins' spokesman, Zachary Deluca, said "the city is still exploring avenues for funding as well as eyeing other potential solutions, including ... a new location, to mitigate the issue."

Hopkins didn't wish to be interviewed, deferring to police.

More: Providence received hundreds of noise complaints. But who's listening?

Brown University study finds noise in violation of local law

Last year, DiMeo contacted Juliet Fang, a Brown University undergraduate student and researcher.

Fang recalled the conversation, which DiMeo initiated after seeing some of Fang's writing in the Brown Daily Herald on the impacts of noise.

"[DiMeo] said, 'Hey if you’re interested in noise pollution, boy do I have a story for you,'" Fang recalled.

DiMeo talked to Fang about the gun range, and eventually became an investigator on Fang's research on noise pollution coming from the site.

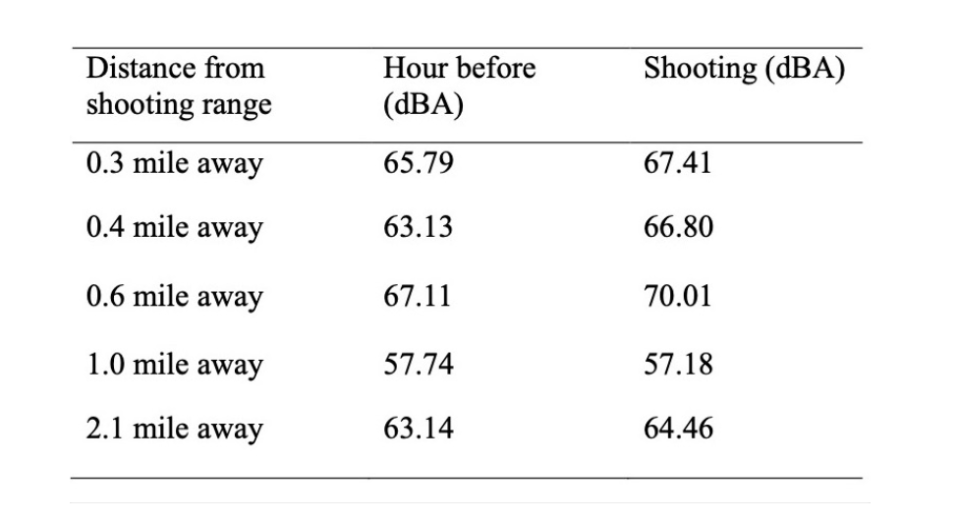

From November 2022 to April 2023, Fang used decibel meters placed varying distances from the range, some as little as 0.3 miles away – the distance of DiMeo's house – up to 2.1 miles away. Fang compared the average decibel levels before firing began with those during the time firing was occurring.

At 0.3 miles away, the sound reached 65.79 decibels without shooting, and rose to 67.41 decibels with shooting. At 2.1 miles away, the change was similarly small; 63.14 decibels without shooting, and 64.46 decibels with shooting.

That's all around the level of people having a normal conversation. At 70 decibels, it's like hearing a dishwasher.

But Fang also found "gunfire noise in Cranston can reach 82 decibels (dBA) during shooting periods, approximately the loudness of the interior of an airplane," she wrote, noting that it far exceeds the 55-decibel allowance in Cranston's noise ordinance. That reading came from a spike recorded 0.4 miles away, Fang said – farther from the range than DiMeo's home is.

But when Cranston police went out to conduct their own tests, their data didn't agree with Fang's numbers.

Police conducted their own tests. Here's what they found.

In September 2022, Cranston police conducted their own noise tests in DiMeo's neighborhood, and found levels were within the limits of the noise ordinance. A police report says that near DiMeo's house, during a "volley of rifle rounds fired a max decibel reading of 53.8 [decibels] was obtained." Police also captured video of their experiments, filming the readings on their decibel meter.

While the meter is recording that the sound is not in excess of the ordinance, the gunfire in the video is highly audible and wouldn't constitute a typical type of noise in most neighborhoods.

But one question remains: How could different devices generate different readings? According to Fang, Brown's noise equipment is "definitely more sensitive than a handheld noise monitor," which the police used, and some of Fang's data collection occurred when the Municipal Police Academy was using the range. Also, Fang's research analyzed average sound peaks during hour-long blocks of shooting rather than shorter snippets.

More: Here are the noisiest parts of Providence, based on 5,000 noise complaints called to police

This year is supposed to be quieter. Neighbors are still on edge.

Winquist expects a quieter year without the Municipal Police Academy. But neighbors still express lingering anxiety over the noises they're hearing.

"I cannot take this … I wake up every day and I’m like, how bad is it going to be? I’m at the breaking point," said DiMeo. "I really am."

As The Journal has reported in past stories on noise pollution, excessive noise in one's neighborhood may trigger stressful physical reactions that contribute to high blood pressure and keep the body in a constant state of fight-or-flight readiness. Generally speaking, that's an unhealthy place to be.

That's not revelatory. Noise was declared a public health hazard in 1968 by then-U.S. Surgeon General William Stewart, who recognized the threats the way the country had begun recognizing air pollution years before.

"It’s unnerving," DiMeo said. "It’s all the things that all the science says that happens when you have this kind of noise pollution."

The city and its residents seem to have two options left: Either the range moves or its neighbors do.

Fang, for her part, just hopes that her work backs up local frustrations with hard evidence.

"This puts quantitative numbers on their concerns," she said. "So the idea is it will attract more attention from the local government ... Maybe this will pique their interest a little more."

To learn more about noise from the Cranston range, see Fang's report and visit Brown's School of Public Health on Nov. 14 at 5:30 p.m. for a panel discussion in Room 241. The event is free to the public, and dinner is provided.

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Cranston police firing range has neighbors complaining about noise