'Nope': How this survivor of a fiery print shop explosion set his own course to recovery

There was no warning before the blast.

No sound, no smell, no siren. No deep rumble to stir unease. No discernible change in the air at Platinum Printing, a family-owned business in a Chandler strip mall where, right up until 9:23 a.m. on Aug. 26, 2021, everything had been operating normally.

At that moment, Dillon Ryan was sitting at his computer typing an email. Over his left shoulder, something bright and yellow flashed.

The next thing he knew, he was flat on his back, staring up at the cloudless sky. The ceiling had been blown away.

The smell of burning metal bit through smoky air. The blast had bowed out the walls and shifted mechanical print units that weighed thousands of pounds. Small spot fires burned amid the debris. Water dripped from fire sprinklers, some still in place, and others knocked to the ground, where they spurted aimlessly. Somehow, a rack of thick paper rolls had remained intact.

The print shop he owned with his brother, Andrew, was in ruins.

Dillon stood, adrenaline coursing through his veins. He glanced toward the front of the shop, where his employee, Parker Milldebrandt, was also getting to his feet.

The two of them had a surreal conversation. What’s going on? I don’t know. Let’s get out of here. Now.

They clambered over machines and waded through rubble, making their way toward what had once been the storefront. The floor-length windows had completely blown out. The door was gone, splayed 100 feet away by the Jack in the Box across the parking lot.

As Dillon stumbled out into the searing August sun, his brain was wild with possibilities. What happened? Had a plane crashed into the store? Had someone bombed them? What the heck had just happened?

Then: Where’s my brother?

Looking back at the shop, all he saw was smoke and chaos. My brother is dead, he thought to himself. That’s it. Gone. His mind, racing, veered to how he would tell Andrew’s family.

Other business owners and shoppers, scared and confused, had begun to congregate in the parking lot. Dillon saw bystanders tending to Glenn Jordan, who worked at an eyeglass store a few suites down, and who appeared to be on the ground in pain. Others came up to him and Milldebrandt to see if they were OK.

Panicked, he began to shout that his brother was still inside. A few people went over to check out the store. Some time passed, maybe a couple of minutes. Each second was emotional agony.

Then Andrew emerged from the smoke.

An enormous wave of relief washed over Dillon. But it quickly turned to horror as he saw what his brother looked like. Andrew’s shirt was tattered, the fabric blown to pieces. His face was streaked with dirt and debris.

Wait, Dillon thought. Do I look like that?

That’s when he looked down.

Aftermath: August gas explosion at print shop shutters Chandler Sunset Library at least 4 months for repairs

A busy, routine life

Sitting in a Chandler cafe more than two years later, Dillon and his wife, Casi, talked about the explosion that ripped through Platinum Printing that day. About the injuries Dillon sustained, his long recovery, and how what happened changed them.

As they told their story, the couple, who married in 2016, finished one another’s sentences, turned to each other to confirm key facts, and — occasionally — issued tactful corrections.

There was a lot going on in August of 2021. Three months earlier, in May, they had welcomed their second child, a girl named Layla. Casi had just returned from maternity leave to her job at a bank, which she had done from home since COVID.

Their son, Carson, had just turned four. Some days, he went to daycare, and others, he stayed home with Casi and underwent behavioral therapy with a visiting professional.

“And then Dillon worked full time, over time, all the time,” Casi said.

“Yeah,” Dillon said. “Sometimes weekends.”

His hours were technically 8-to-5, Monday through Friday. But it was a family business. Dillon’s father and older brother, Andrew, had opened it in 2007 when Dillon was just 15 and had high school and basketball on his mind. He joined his father and brother in 2015 after graduating from Arizona State University, and threw himself into growing the business, soon taking over his dad’s 50% ownership stake.

He pulled long hours when he had to.

“But I'd make it home in time to do dinner, play with the kids for maybe 30 minutes, and then tuck them in for bed and then rinse and repeat the next day and so on,” he said.

“We were very routine,” Casi said.

“Very routine,” Dillon agreed.

A chaotic scene

As he looked down, Dillon looked at his pants. They were soaked in blood.

He looked at his arms. The skin had been blown off. Skin hung off his fingertips. He reached around to his back. The short-sleeved shirt he was wearing had fused with his skin there.

Then he registered that his head felt hot.

He reached up to his trucker cap, which he had been wearing backward. He couldn’t remove it. It was as though it had been superglued to his head. The cap had melted and fused with his hair.

As he took in his injuries, Dillon said, he felt no pain. His body was still in fight-or-flight mode, overwhelmed by the incomprehensible explosion. What had happened?

Later, he would learn that there had been a natural gas leak. Gas had escaped from a prematurely degraded pipe, silently accumulating in the attic of Platinum Printing until something — something as small and routine as the AC turning on, or the flick of a switch — set it off. Boom.

But, in that moment, nothing made sense. He and Andrew ran a print shop. Their chemicals were ink and toner. Their machines churned out pamphlets and blueprints and signage. What could have triggered an explosion of that magnitude?

“I couldn't even give a guess,” Dillon said. “I was just making crazy assumptions at that point.”

Time passed in a blur. Dillon had left all his belongings in the shop, but the other two men had their phones. He called Casi, first from Milldebrandt’s phone, which she didn’t answer, and then from Andrew’s, which she did. Emergency vehicles screamed to the scene, and fire rescue units and paramedics began urgently tending to the injured men.

They moved Dillon into an ambulance, cut off his clothes, administered an IV, and headed for the Arizona Burn Center in downtown Phoenix.

In the ambulance, the pain started to kick in.

'We really didn't know how bad it was'

When her phone first rang, Casi was working from home, or trying to.

She had only just returned from maternity leave and was still nursing Layla. Carson was home from daycare, working with his therapist downstairs. Dillon’s mom was there, to help out.

Casi screened the first call, from an an unfamiliar number. Then her phone rang again, this time her brother-in-law's name displaying on caller ID.

She picked up. It wasn't Andrew, but Dillon. She listened as he relayed a few brief, unbelievable facts: There’s been an explosion. I’m OK. I’m going somewhere in an ambulance.

“I'm like, What do you mean? There's like an explosion? Like a plane hit you? Something blew up? Did one of your machines go crazy?” Casi said.

Her head spun with possibilities. What had happened to her husband?

It was doubly bizarre to hear Dillon’s voice against the heft of what he was describing. He had been in an explosion, was badly hurt enough to need an ambulance, and yet there he was on the other end of the line, speaking coherently.

Casi sprang into action, called in family reinforcements, figured out what to do with the kids.

At first, she went to Chandler Regional Medical Center, not realizing that Dillon was being taken to Valleywise Health in Phoenix. It wasn’t until she was on the way to the burn center, her mom driving and with Layla in tow, that she saw photos of the print shop, mangled and terrifying, in online news articles.

When she finally arrived, Dillon was asleep, in a medically induced coma. Casi wasn’t allowed inside because of COVID restrictions. She and her mom checked into a nearby hotel and waited for a call.

Finally, it came. Dillon was awake. She could see him.

The first person she encountered was Dr. Kevin Foster, the director of the burn center. He took one look at her face, Casi remembered, and told her: “He’s going to be OK. It looks bad, but he’s going to be OK."

She remembers sitting by Dillon, who was awake and talking. He told Casi the same thing.

“He was like, 'I think it'll be a few days,'” Casi remembered. “Like, ‘I'm fine. They're going to clean me right up and I'm fine.’”

“We really didn't know how bad it was until the days following.”

A few days after the explosion, Dillon was told he would be in the hospital for two months.

At that point, the pain was excruciating. He had endured debridement surgeries, procedures to clean up his wounds and remove dead skin, and was lying on his back, wrapped up like an Egyptian mummy. He had sustained second- and third-degree burns to 25% of his body.

His pain was so immense that it was difficult to sleep. He had lost fine motor skills, making it tough to do the simplest thing like pick up a fork. The superficial burns on his face had swelled so much that they had forced his eyes shut.

Still, the news came as a shock.

“I'm thinking to myself, I got a wife and kids at home. Like, you're telling me 60 days I'm going to be in here?”

Dillon laughed as he remembered his reaction.

“Nope,” he said. “It ain't going to happen.”

'He needs you'

At home, Casi tried to explain to Carson what had happened, with help from a teddy bear.

The staff at the burn center had given it to her — they wrapped it with bandages in the places Dillon had been burned. It would help her explain, they said.

More than two years later, Casi fought back tears as she remembered the tough conversation.

“So you bring this bear home,” she said, switching into second person. “And you're trying to tell this four-year-old — he literally just turned four — like, ‘Dad's hurt. He's going to be okay. But he's not going to be home for a while.’ And then you show him this bear, and you're trying to explain where he has these Band-Aids on.”

Carson didn’t understand right away. But then night fell, and he realized Dad — the reader of bedtime stories, “the life of the party,” his best friend — wasn’t there to put him to bed.

“That's when he just lost it,” Casi said.

It was hard. Carson missed Dillon. Dillon was scared for Carson to see him. By his second week in the hospital, Casi stood firm. “You have to talk to him,” she told her husband. “I know you’re scared, but he needs you.”

So they FaceTimed, joking about Dillon’s appearance being like a mummy costume.

It was tough, Casi said, seeing her usually positive husband so down. To see him in so much pain. To see him struggle with the tiniest things, like getting out of bed or feeding himself, and knowing there was nothing she could do to help, that it was crucial to his recovery that he do those things himself, even when he couldn’t.

Even when it hurt.

“I mean, there is nothing I can do,” she said. “All I can do is sit there and talk to him when he wanted to talk or sit there silently when he didn't want to talk.”

She put her own emotions on hold, doing what she had to to keep the family functioning, all the while feeling like a zombie. She’d sit with Dillon, feeling helpless, and then drive home and flip the switch to Mom. Feed the kids, bathe the kids, put them to sleep. Try to maintain some semblance of routine.

“I feel like I was okay until he got home,” Casi said, reflecting on the time Dillon spent in the hospital. “I feel like moms, or women in general, are able to just focus in. This is what needs to be done. This is where I need to be. And not feel the feelings until later.”

Climbing back: A Phoenix doctor helped burn victims recover. Then he helped them summit Mount Kilimanjaro

'She kicked my butt'

Dillon was determined to shorten his hospital stay in any way he could.

He would pick his care team’s brains, asking doctors, nurses, physician assistants and therapists what milestones they were looking for and how he could reach them. Whatever they said, he did.

Working with occupational therapist Connie Greiser, he learned to embrace pain as part of his recovery.

Greiser, who has worked at the Arizona Burn Center for 16 years, said there is often a “love-hate relationship” between burn survivors and occupational therapists. It's part of her job to help people see the other side of their recovery, which can be very difficult.

“We make people hurt by moving, but that’s the only way to get better,” she said. “Once they get over that hump, it’s easier for them. They’re more independent. But it’s sometimes a hard hump to get over.”

But Dillon was always very motivated, willing to do whatever she asked.

He puts it this way: “She kicked my butt.”

“I would dread seeing her walk in those doors,” he added. “But every time she did, I was a little bit better.”

Two and a half years on, Geiser still remembers Dillon’s motivation, and his supportive family. “He is one that I knew was always going to succeed,” she said.

And he did, faster than expected. His decisive “nope” to two months in the hospital came true. He puts it down to a few things. Luck. Diligence. Mindset. The motivation of being home with his family.

But he also had a secret weapon.

For his entire hospital stay, Dillon shared a room with Andrew. They pushed each other toward recovery in the way only a sibling can.

The brothers had different injuries — Andrew’s burns were worse on his legs, Dillon’s on his arms — and struggled with different things. Andrew could pick up the phone and order them breakfast, but it was easier for Dillon to get up and walk around, at least before he had skin graft surgery on his thigh.

“The first couple of breakfasts that I had delivered, I barely ate them because I couldn't even hold a fork,” he said. “But I would look across from me and I would see Andrew picking up a fork and eating his food. And eventually I said to myself, ‘if he's doing that, I have to do that too.'"

If Andrew got up, Dillon got up. If one of them went to the gym, the other would move any way he could, even if it was just circling the room on a walker. After a few days of Andrew placing both their breakfast orders, Dillon insisted on doing his own.

It was 24-7 motivation, a productive sibling rivalry expressed in statements like: "You just got to get up, dude.”

It was also an antidote to ennui. A familiar voice when Dillon’s eyes had swollen shut and turned his world pitch black. A way to combat the deep loneliness of the early hours when they couldn’t sleep because of the pain.

“One of my fears was I don't want my brother to be discharged before me,” Dillon said. “And then I'm left here alone.”

In the end, Dillon spent exactly two weeks in the hospital, followed by six days in a rehabilitation facility in Mesa, where he underwent physical and occupational therapy and Casi learned how to be his nurse. Andrew stayed one additional night in the hospital before going straight home.

Driving away from rehab felt freeing, Dillon said. He had a lot of healing still to do, but it would happen at home, with his family.

Seeing colors: Is that purple? Glasses reveal the world of vivid hues for people with color blindness

Finding purpose after dark days

He may not have spent it all in hospital, but Dillon’s recovery was still long and arduous.

Healing from burn injuries takes time, he said, a challenge to his impatient nature. It felt like the universe had ordered him to slow down.

There were dark days, moments he felt isolated and trapped. But Dillon was determined not to let them consume him.

“I always wanted to make sure that I had a positive mental outlook,” he said. “Because I knew that for me to build back to where I wanted to be, it wasn't just for me.”

“It was also for my wife, to give her a good quality husband at the end of this, my kids to have a good quality father after this.”

His goals were things like being able to pick up Carson. To walk around Disneyland. Slowly but surely, he got there.

Casi tried to go back to work, but it was too hard. Dillon needed her, to be his nurse, his chauffeur, his moral support. She quit her job at the bank.

“But he’s OK,” she said. “He’s OK now. And it’s time for me to start my next adventure.”

In February, she will go back to school to train as a respiratory therapist. She might end up helping premature infants, with underdeveloped lungs. Or older people, struggling to breathe through disease. Or people with allergies, inspired by Layla, who is now two, and terribly allergic to dogs.

“Everyone needs to breathe,” she said.

Dillon hasn’t returned to the strip mall.

He’s seen the pictures. But it’s not that close to where they live. Going into Tempe and Phoenix, they tend to drive on the freeway, so they don’t pass by. And Chandler Mall, where the family hangs out, doesn't take them by there either. And —

“ — I think it's not something you necessarily want to see,” Casi said, gently interrupting her husband.

“Yeah. I mean — ”

“Because we’ve been in the area, and you had no desire to drive by.”

“I lived it, you know?” Dillon said. “I know what it looks like. I know what that experience was like and what that scene looked like. And I'm sure it looks a lot cleaner than it did when I was there last. But, I just, I'm more of a one step forward kind of guy instead of living in the past.”

He’s not interested in reliving it. Especially now.

In September, he and the other injured men reached a settlement with Southwest Gas, which operated the gas line, and Chevron Phillips, which made the pipe.

The details are confidential, Dillon said. But the agreement felt like a release from the uncertainty, financial instability, and anger he and Casi had dealt with for two years.

To him, Dillon said, the settlement “almost felt like the last piece that was needed to fully release myself from the past."

Some pieces remain. He only wears long-sleeved shirts out of the house now, even in summer. He’s self-conscious about the scars on his arms.

He doesn’t mind talking about the explosion, so long as it’s on his own terms. He’s mentioned it on occasion, and people have said things like “I noticed your hands, but I didn’t want to ask.”

He wants to wear short sleeves again. To be more comfortable opening up to people. He’s working on it.

A lot of it is not wanting to go down rabbit holes. To have to delve into the enormity of what happened in response to an innocent question like “So what do you do for work?”

“I'm like, ‘Well, I have a story for you,’” Dillon joked, “‘but how much time do you have?’”

Right now, he isn’t working.

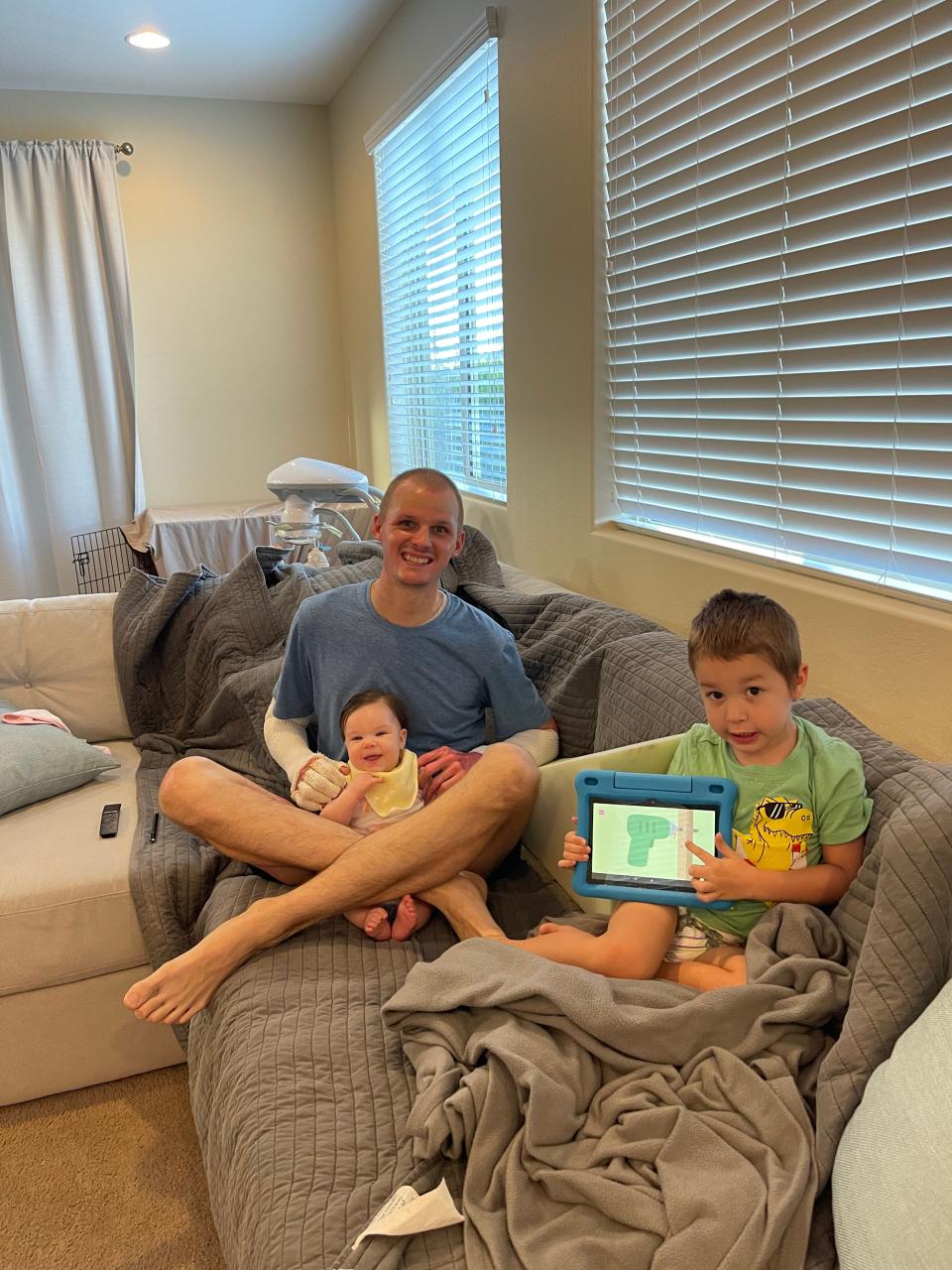

Last May, he took a volunteer position as a J.V. basketball coach at a San Tan Valley high school, something he’s always wanted to do. And he spends every minute he can with Casi, Carson and Layla.

Maybe it’s the sleeves, maybe it’s people holding back, maybe it’s the way Dillon has learned to navigate conversations about his injuries.

But in two and a half years, he hasn’t really faced the question: What happened to you?

The explosion made him think about what is really important, he said. It made him take a cold, hard look at himself, to grapple with a more existential question.

“If I died in this explosion, would I be happy with the way that I led my life? My relationship with my kids, my wife, my family?” Dillon said. “And my answer was, no, I wouldn't be.”

He thought about all the extra hours he had spent in the shop. The moments of Carson’s life he had already missed. And he decided to change.

“Money and jobs and work, those all come and go,” he said. “They'll always be here in life, but you won't.”

His family is his legacy, Dillon said. His priority. For now, it’s what gives him purpose.

Lane Sainty is a storytelling reporter at The Arizona Republic and azcentral.com. She writes about interesting people, places and events across the 48th state. Reacher her at lane.sainty@arizonarepublic.com.

You can support great storytelling in Arizona by subscribing to azcentral today.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Chandler gas explosion: How Dillon Ryan survived print shop blast