North Carolina autopsy backlog brings pain, financial crises to grieving families

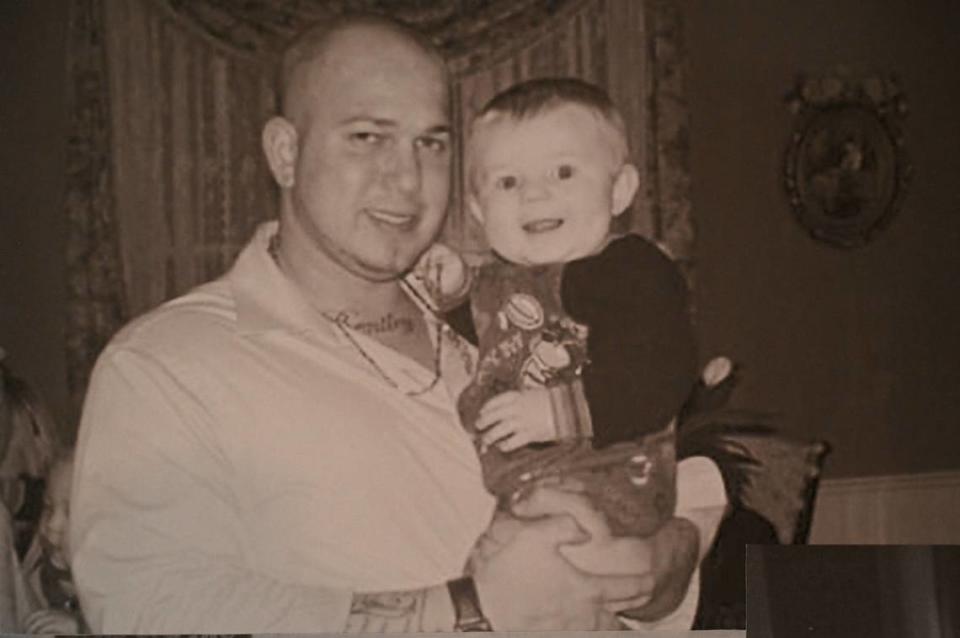

Valerie Smith-Ragland was devastated after Granville County sheriff’s deputies shot and killed her son.

Makari Jamel Smith – an Army veteran in the midst of a mental health crisis – fired a shotgun during a February 2022 stand-off with the deputies before one of the officers shot him to death, police say.

Then, thanks to a crisis gripping North Carolina’s medical examiner’s office, things went from horrific to worse. Because of a lengthy delay in completing the autopsy report, Smith-Ragland was forced to wait more than a year to receive life insurance she was entitled to.

The practical nurse had lost her husband and his income just three months earlier. She had missed two mortgage payments and feared she’d lose her home by the time the state investigation finally closed — more than a year after her son’s death.

“You’ve got family members going through the grieving process,” said Smith-Ragland, who didn’t receive the insurance money until this April. “To put this on top of it? Something has got to be done.”

Such delays have grown significantly worse over the past 10 years. When people in North Carolina die unexpectedly, required medical investigations usually take more than 20 weeks. And in nearly 1,400 cases since 2020, they took more than a year, a Charlotte Observer and News & Observer investigation found.

The system is log-jammed here chiefly because there are too many bodies and too few pathologists and toxicologists to handle the load.

The situation is “tragic” and “unacceptable,” admits the person running the state Department of Health and Human Services.

“Bottom line, plain and simple, the medical examination system is in crisis,” DHHS Secretary Kody Kinsley said in an interview.

That crisis is heaping more burdens on grieving family members during one of the worst periods of their lives. Some can’t touch funds they are entitled to inherit, leaving their biggest bills unpaid. Many must wait months for the answer to a burning question: Why did their loved one die?

The delays can harm others, too. Prosecutors and police say the logjam can delay charges against dangerous criminals, leaving them free to victimize others.

Why does it take so long?

The national association that sets standards for medical examiners requires accredited systems to complete 90% of autopsy reports within 90 days. North Carolina completed just 24% of cases that quickly in 2022, the newspapers’ analysis of state data shows.

The median length of time to complete cases — the middle value, in other words — was nearly five months. That’s the lengthiest in more than a decade.

Families caught in these delays have no choice but to wait. Only the state can perform the medical examinations that North Carolina law requires after suspicious deaths. And only the state can issue the death certificates families need to access insurance money and other assets.

After violent, suspicious or unexpected deaths in North Carolina, part-time medical examiners – usually doctors or nurses – examine bodies. If the cause of death isn’t obvious, they request autopsies.

Bodies are brought to forensic pathologists who either work for the state or perform autopsies on a contract basis. In many cases, blood, saliva and other bodily fluids are shipped to the chief medical examiner’s toxicology lab in Raleigh, which tests for drugs and other lethal substances.

Pathologists lay out their observations, along with conclusions about why a person died. That report is then reviewed by the chief medical examiner’s office. Only then can a death certificate be issued.

Typically, bodies are refrigerated at funeral homes or hospitals for one to five days before pathologists examine them. Then the bodies are released to funeral homes so the families can make final arrangements. But it can be months before autopsy and toxicology reports are completed.

A shortage of forensic pathologists and an increase in opioid deaths have created challenges for medical examiners offices across the country. But the problems appear to be severe in North Carolina, according to several national experts who were told of the state’s turnaround times.

Medical examiner cases grew more than 30% over the past three years. Drug overdose deaths, which soared 58% from 2019 to 2022, are largely to blame.

“These increases flooded the system, and the team is still working to catch up,” according to an email from DHHS spokesperson Bailey Pennington Allison.

Pathologists at the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner in Raleigh are performing, on average, 557 autopsies apiece each year – more than twice the number recommended by the national accrediting group, Kinsley said.

“They’re working incredibly long hours. They’re working incredibly hard,” he said. “But that is far outside the bell curve of what they should be doing.”

Staff vacancies, which plague many North Carolina agencies, have made the problem worse. One out of four positions at the chief medical examiner’s office are vacant, according to DHHS, which oversees the office. Shortages of forensic pathologists – highly trained doctors who perform autopsies – are particularly pronounced. Nine of the state’s 16 forensic pathology positions are vacant.

The medical examiner’s office now has just one forensic toxicologist to certify all drug casework, DHHS says. Two more people are training to be qualified as additional forensic toxicologists so that they’ll be able to handle some drug cases. But DHHS officials say they can’t predict when all needed positions could be filled.

Such strains on the system inevitably result in one of two things, one expert said.

“You’re either going to get delays in getting reports out or people are going to have to start taking shortcuts,” said Dr. Patrick Lantz, a longtime forensic pathologist at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center in Winston-Salem.

Waiting and waiting for autopsy results

Many miles from autopsy rooms, North Carolina families pay a price for these problems.

On a Friday morning in May 2019, Donna Burnette was at her home in Indian Trail preparing for a beach trip with her son, Kyle, and his two sons when one of the boys found Kyle unresponsive on his bed.

Burnette called 911, but paramedics couldn’t revive the 32-year-old.

Burnette and her husband suspected their son’s death was related to some problem with medications he took for anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder and other problems.

“I was scared that he got some sort of medication that had something else in it,” said Burnette, whose son took methadone to help him beat an addiction to prescription painkillers.

Burnette had another close family member who’d taken methadone. If something was wrong with Kyle’s medication, she wanted to be able to warn anyone else who might be in harm’s way.

Each time Burnette and her husband called the medical examiner’s office, they were told the investigation was not finished.

“It got to be a year. And we said, ‘This is ridiculous,’ ” Burnette recalled.

Fourteen months after Kyle died, they received the autopsy report, which showed that Kyle died from excessive levels of methadone and diazepam, a sedative commonly prescribed for anxiety. Burnette thinks the overdose was an accident.

“I hope other people are able to get answers sooner than we did,” Burnette said.

That’s important for families and for the greater good, public health experts say. Information from autopsies helps target efforts to prevent deaths. If a new drug causes overdose deaths, for instance, communities need to know.

“When you delay the answers this often, the information comes after you’re able to act on it,” said Dr. Victor Weedn, professor of forensic sciences at George Washington University.

Funding lower in NC than other states

A 2014 Charlotte Observer investigation into problems plaguing North Carolina’s system for probing suspicious deaths also uncovered delays in wrapping up medical examiner investigations. But today’s delays are worse. The median length of time for completing investigations has grown by about 34% since 2014.

North Carolina’s turnaround times raise cause for concern, according to Dr. James Gill, chief medical examiner for the state of Connecticut.

“That’s much longer than I would expect in a properly staffed death investigation system,” said Gill, a former president of the National Association of Medical Examiners. “ … That speaks to something more systemic.”

DHHS declined multiple requests to make the state medical examiner – Dr. Michelle Aurelius – available for an interview. DHHS spokesperson Kelly Haight Connor said staff in her office were too busy to speak with a reporter.

Dr. Joyce deJong, who heads the national medical examiners group, said she knows Aurelius is an excellent pathologist. She suspects that her office’s backlog results from too few resources, not too little will, she said.

“It is not because people are lazy,” she said. “...They have good people. They just need more of them.”

North Carolina’s medical examiner’s office has for years operated with less funding than most other states, previous reporting by The Observer has shown.

The average state medical examiner system spent $1.76 per capita on its death investigation system — or about $2.64 in today’s dollars, according to the most recent national survey data from 2007. Fifteen years later, the budget for the North Carolina office is $15.7 million: less than $1.50 for every North Carolina resident.

The starting annual salary for forensic pathologists in North Carolina is about $177,500, lower than what’s offered by South Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky and West Virginia, DHHS staff say. Nationally, the average pay for pathologists is $339,000, according to a recently released Medscape report on physician compensation.

Private employers also pay substantially more, state officials say.

“We’re losing our staff to positions all across the country,” Kinsley said. “…This system is just currently not resourced to meet the need.”

Autopsy report delay threatens student’s stay at college

The toll of these delays can disrupt lives across generations, Mark Tango has learned.

When Tango and his ex-wife, Leigh Cartier, were married, they bought insurance policies naming each other beneficiaries. After their 2015 divorce, they kept that arrangement and agreed not to drop the insurance until their oldest of three sons turned 21.

Tango was home in New Hampshire in April 2021 when he was notified that Cartier, a 49-year-old nurse, was found dead at her Chapel Hill home. A large handbag containing controlled substances was found near her body.

The Orange County Sheriff’s Office investigated and found no signs of foul play. But Cartier’s insurance company would not pay out death benefits until the autopsy report was completed.

Cartier’s death left Tango without child support payments — and without the financial contributions his ex-wife had planned to make toward her son’s tuition at a small college in Massachusetts.

That meant Tango couldn’t afford to pay the tuition for his oldest son’s first semester. Campus officials agreed to let his son start school, but made it clear he would not return for the second semester until the fall bill was paid in full.

“It caused enormous pressure, anxiety and stress,” Tango said. “I was held hostage.”

Tango did everything he could to move things forward. He called the state medical examiner’s office at least 50 times to check on the status of the investigation, he said. Each time, he recalls, the receptionist’s answer was the same: “I’m sorry, Mr. Tango. Still pending.”

In December 2021, he hired a lawyer to help him push for the case’s resolution. And he sent an urgent fax to the state medical examiner’s office.

“We understand the workload on you and the staff however we are at a tipping point…,” it read.

The medical examiner’s office concluded its investigation soon afterward. The pathologist who wrote the autopsy report stated that the death was “highly suspicious for a drug toxicity,” but did not determine the cause of death.

The day before Christmas, eight months after his ex-wife’s death, a courier finally carried the insurance check to Tango’s door.

Although he and his family weathered the ordeal, he suspects other families have been devastated.

“Think of a family that just lost their sole breadwinner,” he said. “How are they going to pay next month’s mortgage?

“How many people are suffering?”

State must invest more, NC DHHS secretary says

Paying staff members more could help attract pathologists to North Carolina, experts say.

While forensic pathologists in North Carolina now earn from $177,000 to $219,000 per year, a number of cities where the cost of living is lower than Raleigh are offering new medical examiners 40 to 50% more, an Observer review of job postings from around the country found.

Aurelius’ office conducts autopsies for 34 North Carolina counties and contracts with eight independent autopsy centers, which cover the remaining 66 counties. But the state pays those centers just $2,800 per autopsy — less than half the average cost, according to DHHS.

As a result, DHHS said, the state lost the services of one regional autopsy center. Another center reduced the amount of work it does for the state. Both events increased the workload for the state office.

DHHS for several years running has asked lawmakers for more money, Kinsley said.

At his department’s recommendation, Gov. Roy Cooper’s budget proposed boosting salaries and requested $7.3 million more so that the state can pay regional autopsy centers for the full cost of performing autopsies.

The House and Senate budget bills would increase the autopsy fee paid to contractors to $5,800. But they call for the state to pick up just a portion of that amount, with the rest usually being paid by the county where the deceased person lived.

Kinsley said he’d like to see a “wholesale investment” in raising the salaries of staff members at the chief medical examiner’s office. “The legislature has got to grow the system,” he said. “And the only way to do that is by investing in it.”

Dr. Ljubisa Dragovic, a nationally recognized forensic science expert who runs an accredited medical examiner’s office just north of Detroit, agreed that the figures from North Carolina suggest that state officials need to spend more money on the medical examiner system.

“Those vacant positions should be filled with a plan rather than waiting for a miracle,” said Dragovic, who serves as chief medical examiner for Oakland County, Mich. and as an editor on prestigious forensic science journals.

‘I just needed answers’

Cynthia Parker had no questions about why her daughter died on Feb. 3, 2022.

Yasmin Vitalis, 25, was found unresponsive on a living room floor in Fuquay-Varina. The young woman had experienced trauma in her life and had “turned to drugs to help her feel better,” her mother said. She had overdosed on heroin a number of times before.

But, as required by state law in cases where people die under suspicious circumstances, a medical examiner was summoned to view her body. A blood sample was sent to the state toxicology lab for analysis, but no autopsy was performed.

Parker took out life insurance policies for her children when they were young, but the insurer wouldn’t pay out until the death investigation was completed. That left Parker without money to pay her daughter’s debts and funeral expenses.

Week after week, Parker called the medical examiner’s office in Raleigh. The investigation’s not yet finished, she was told.

In September —seven months after Vitalis’ death — the investigation was finally completed. It concluded that she died from a fentanyl overdose. The insurance money came soon afterward.

Parker said she’s proud to live in North Carolina. But making people wait so long for answers after their loved ones die is inhumane, she said.

“This,” she said, “is just shameful.”

Thousands of families, from North Carolina’s mountains to the coast, have endured similar waits — and many of them have been much longer, according to data the newspapers analyzed. Nine family members contacted by a reporter all reported deep frustration.

Joanne Butts, of Wilson, waited more than a year to find out that her 53-year-old son died inside his Raleigh apartment from hypertension and heart disease. Gaston County resident Steven Michael waited 16 months for an investigation to rule out foul play in the death of his father, who perished in a Dallas, N.C. house fire.

And Concord resident Shelly Alexander waited almost 17 months to find out that a ruptured aorta was behind the death of her 32-year-old husband.

“I just needed answers,” Alexander said, as she struggled to hold back tears. “I needed to be able to tell my kids.”

Public officials, she said, “have to do better.”