North Carolina digitizes slave deeds, paving way to link descendants to deserved reparations

BUNCOMBE COUNTY, N.C. — We know that the prosperity and success of our young nation was built on the backs of enslaved people. But how much do we know about the individual slaves who built it? How they were treated? Where they were sold? And where their descendants live today?

A Buncombe County project that I spearheaded (and am helping to spread statewide) helps answer identifying questions about Buncombe's enslaved population. In doing so, it dispels the national myth that tracing African American lineage to slavery is a near impossibility – and that determining who is owed reparations, and from whom, is too complicated to tackle.

People Not Property digitizes bill-of-sale records, also known as slave deeds, that have been ignored – hidden on dusty courthouse shelves for generations. Partnering with local students, the project started in Buncombe County with the creation of a database of these slave transactions. Records that carry proof of the nation's shameful beginnings (centered around the dehumanization of an entire race) now hold a key to repair and justice for slave descendants.

Thousands of slave records found

The program quickly spread to other counties, and then became a statewide endeavor that will allow families to track slaves who were repeatedly sold across county lines. The goal now is to pull information together into a universal, statewide platform – one that the public will be able to search by October.

Thus far we have uncovered more than 40,000 names of enslaved people in North Carolina, and are completing a framework that can be used by other states who wish to join our efforts.

Already, the efforts in Buncombe County have shed light on slavery's reality.

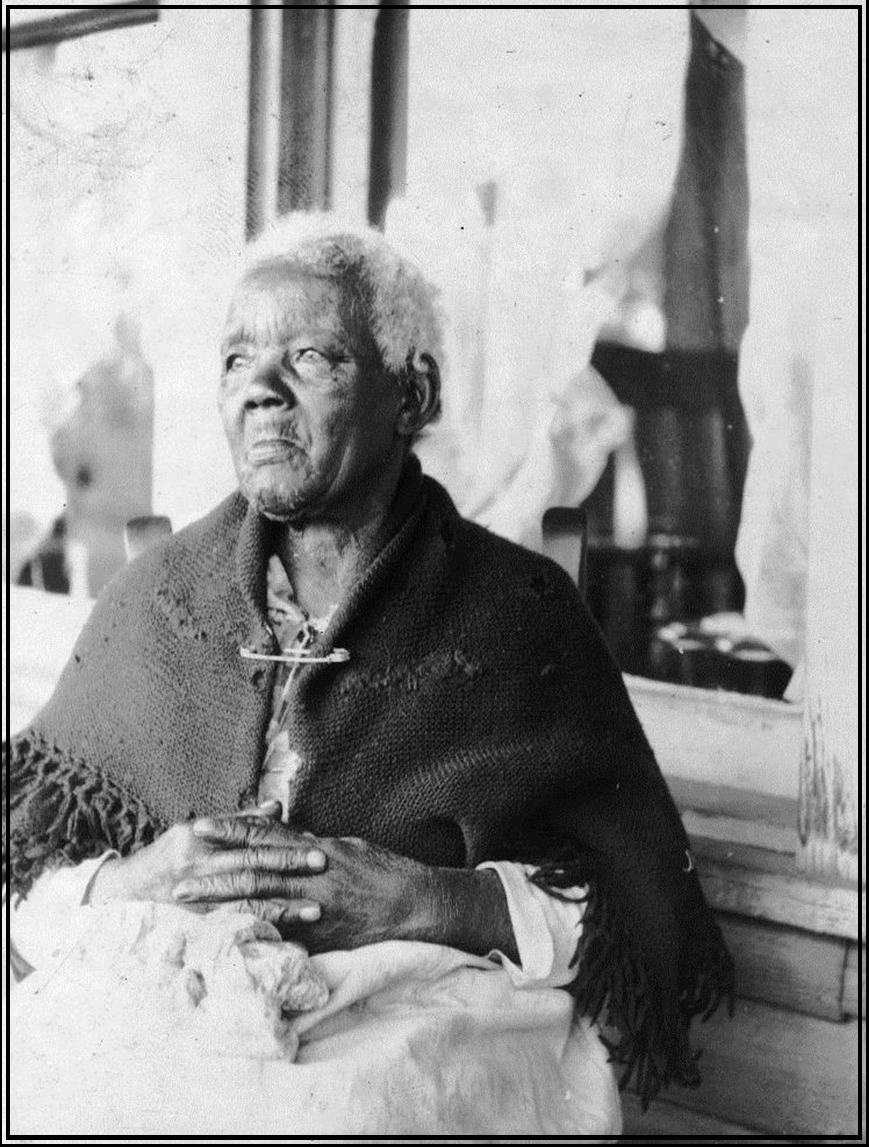

Sarah Gudger, who lived to be 121 and was interviewed near the end of her life in 1937 by the Federal Writers' Project, was a slave in Western North Carolina – a location where the depths of slavery's cruelty and trauma is often downplayed. County slave deeds recorded her sale at the age of 20 for $250. And she recounted, during her 1937 interview, how slave masters tied the wrists of slaves together before beatings and other harsh conditions.

All states record and store documents differently, but slave deeds exist in nearly every state. It is the duty of the custodians of these documents to make them more easily accessible to the public. Archivists and historians have been making such documents accessible for white Americans since this country's founding.

With the increasing popularity of online genealogy platforms and DNA testing, many Americans have embarked on the meaningful journey of tracing their family tree. With relative ease, most white Americans can use online databases to clearly trace their heritage centuries into the past. Historically, Black Americans have been excluded from this research because enslaved people are not listed by name in any census, leaving many Black families with questions.

An answer for reparations

Throughout the country, as government entities begin to explore reparations for Black residents, it is important to transparently document our past transgressions with primary source documents so that we can begin to atone for them.

Slave deeds could provide a vital connection for the distribution of reparations. These documents and others like it might be some of the only official evidence to prove the link between descendants and their enslaved ancestors.

Deeds alone of course aren't enough for families to make full connections between themselves and their ancestors. Members of the public who have searched the Buncombe County site usually have names of ancestors going back generations, and the names of the family members who may have enslaved them. But digitizing these records in an era when there's a lack of accessible information for Black Americans is key to solidifying connections.

Community leaders and citizens shouldn’t wait for someone else to do this work.

Take the time to learn your county’s history. If it was formed before 1865, there are likely slave records sitting on courthouse shelves. Ask your county clerk what they are doing to make the names of the enslaved available.

Making slave deeds easily accessible throughout the country will allow Black Americans to do the profound work of tracing their family history back generations, while also enabling our society to better grasp its history.

Drew Reisinger is the Buncombe County register of deeds.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: N.C. digitizes slave deeds, paving way to link descendants to repair