North Korea is offering Russia weapons – and ski holidays

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

North Korea may be known as the hermit kingdom, but when it comes to accepting cash in exchange for weapons, the state is willing to open up. Yet, the relationship between the isolated state of 26 million people and its former Cold War patron is now not only about money.

Back in September 2023, all eyes were on Putin and Kim Jong-un, as the two rogue leaders met in the Vostochny Cosmodrome, and Kim admired Russian satellite technology. Whilst we may never know for sure whether a cash-for-arms deal between the two states was signed, the prospects look increasingly likely. It is not just a plentiful supply of artillery and shells of variable quality that has headed from Pyongyang to Moscow. North Korea has now upped the ante by providing its desperate Cold War patron with ballistic missiles, particularly short-range ballistic missiles, to use in Putin’s ongoing war with Ukraine.

Earlier this week, the US Treasury sanctioned four Russian entities, including a firing range, a military research facility, and a Russian airline – a state-owned spin-off of the Russian Air Force – for their part in transferring and using North Korean ballistic missiles. Four Russian aircraft were also identified as being complicit in the act, in November and December of last year, sending both North Korean ballistic missiles as well as missile-related cargo in Russia’s direction. Whilst few details are known about the exact movement of missiles, it is not unfathomable for the aircraft to have done a simple direct transfer.

We must remember that North Korea is no stranger to participating in clandestine networks of weapons transfers, which often involve third parties. It formed a key cog in a network of nuclear proliferation – from fissile material to know-how and expertise – commandeered by Pakistani nuclear physicist, A. Q. Khan, in the 1980s and 1990s. This arrangement was revealed to the world exactly twenty years ago, and since then, Pyongyang has developed nuclear weapons of its own; advanced its missile capabilities and delivery systems; and learnt how to leverage a global political environment marred by ever-deeper fissures.

Given the complexity of North Korea’s illicit networks, however, is the story really as simple as it sounds? The routes taken by the Russian aircraft identified to have transferred such missiles – either within Russia or between Russia and North Korea – cannot be tracked, thus playing to North Korea’s advantage. That said, we should also not rule out the sea. One of the many means by which Pyongyang has evaded unilateral and multilateral sanctions is through engaging in ship-to-ship transfers, whether of oil, petroleum, or even North Korean munitions. What is more, monitoring the precise movements of these vessels – let alone their contents – is far from easy, to the benefit of both Pyongyang and Moscow.

Whether the missiles reached Moscow by sea or air, this highly concerning discovery marks the blossoming of the relationship between Russia and North Korea, in creating a new geopolitical axis in opposition to the West. We know that Russia is not just counting on its former Cold War client for weaponry. Iran has also been transferring drones to Russia, and looks set to accelerate its supply of more advanced attack drones and, possibly, ballistic missiles. Yet North Korea is anything but excluded in this relationship. Iran was – and remains – a crucial middle-man for the transfer of North Korean ammunition to the Middle East, as was the case when North Korean F-7 grenade launchers were used by Hamas in their early assaults on Israel.

It’s not just missiles, however, that look set to continue travelling down the corridor between the two authoritarian states. At the same time as the US’s sanctions were imposed, Russian state media announced how Russian tourists would be able to visit the DPRK for ski holidays, later this year. For a country whose borders are yet to open fully following their drastic coronavirus-induced closure in January 2020, this manoeuvre is far from an act of coincidence.

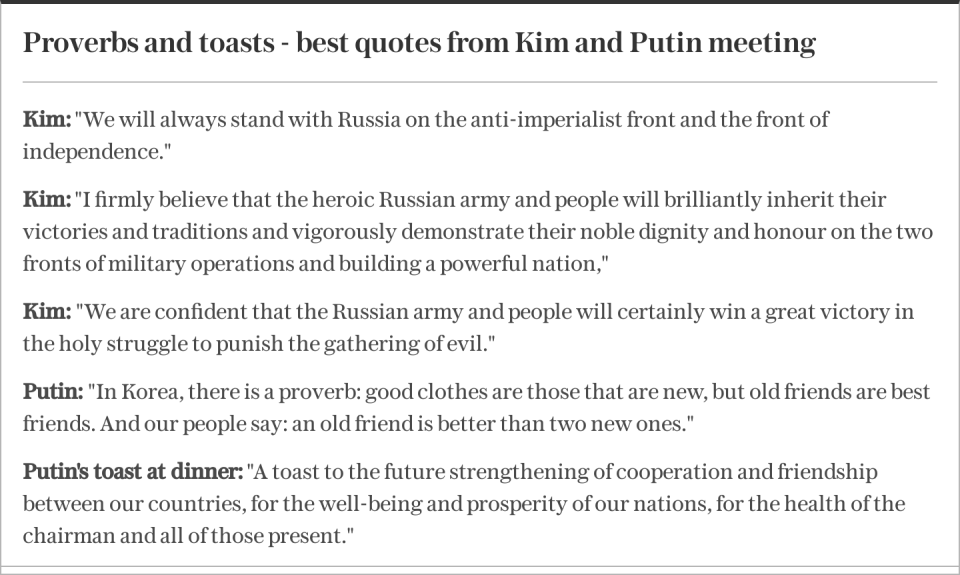

Indeed, perhaps we are now witnessing just exactly what Kim Jong-un meant when, sitting across the table from Vladimir Putin, he announced that North Korea’s relationship with Russia would be a “number one priority”.