North TX parents share breast milk online. Doctors, milk banks want to make exchanges safer

Parents are seeking out a valuable potion full of antibodies and protein for their young ones.

Some are able to make it on their own after giving birth, creating a bond between themself and their child when sharing the potion that helps the child develop a strong immune system and protect them from certain illnesses. For other parents, providing this potion is more complicated, and the pursuit of finding it from other sources can depend on health factors, location or a parent’s social media presence.

On Facebook specifically, parents are connecting through private groups to sell, buy and donate breast milk both nationally and locally. Medical experts describe this as a risky practice, but local mothers who talked to Star-Telegram describe it as an empowering, collaborative transaction that’s provided nutrition to their children when other means have been unattainable.

The “Breastmilk buy/sell/donate DFW Texas and surrounding area” Facebook group has more than 5,000 members who advertise their extra breast milk and also bid or barter for the precious liquid by offering cash, breast pumps, storage bags or other supplies. A Star-Telegram reporter requested and was granted permission to join the private group while informing moderators that the goal was to connect with parents using the page.

Although some offer their milk for free in the group, others sell it per ounce, ranging from 40 cents to 75 cents, according to recent posts. The amount of milk recently advertised has ranged from 300 to 1,900 ounces.

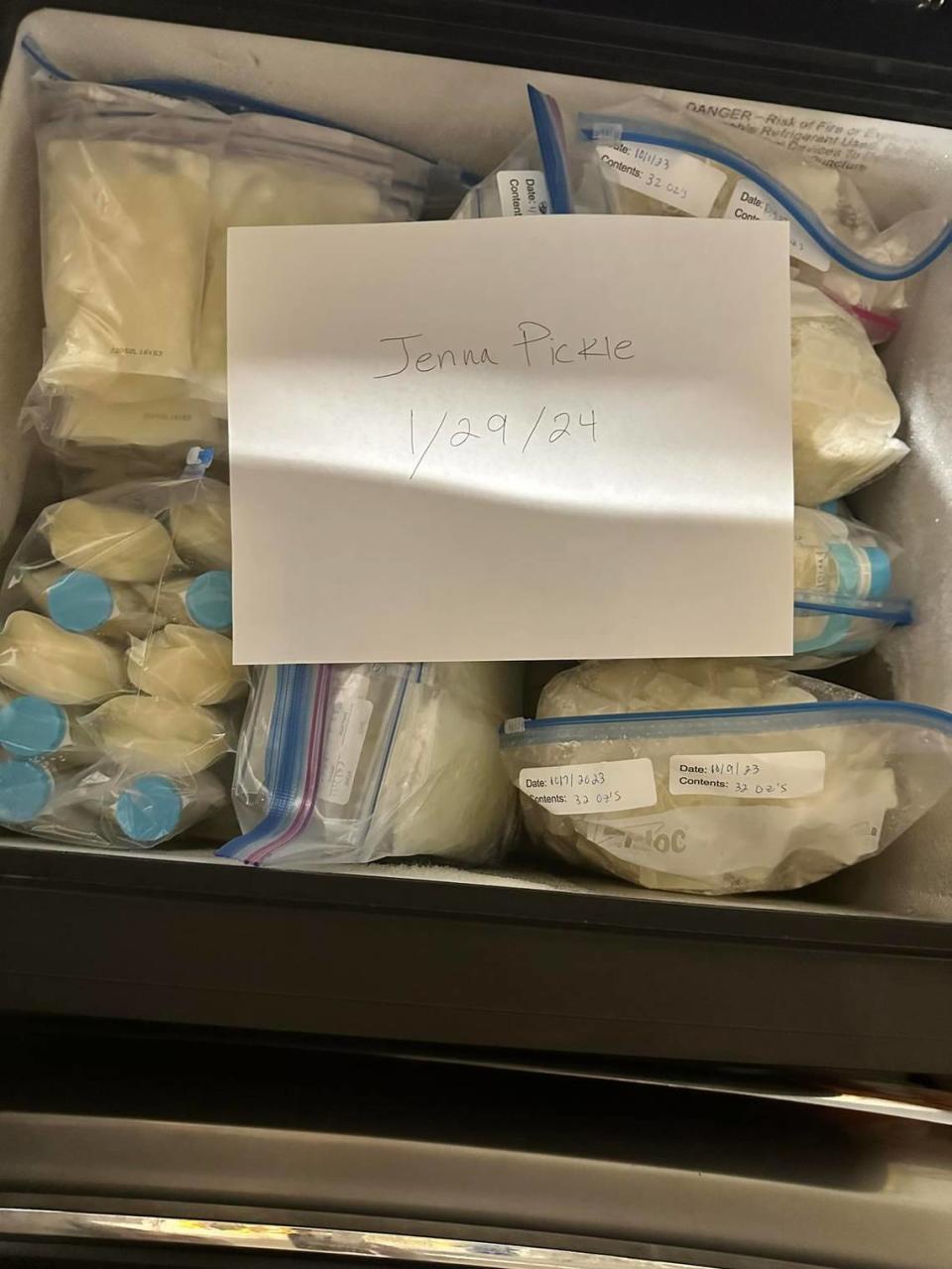

Fort Worth mother Jenna Pickle was among those who shared their milk, posting a photo with frozen white bags marked with dates and portion sizes, in addition to a piece of paper with her name and the date she took the photo. As part of a requirement of making a post in the group, she laid out several bullet points: ZIP code, medications, diet, lab work, details of milk storage, her child’s birthday, her vaccination status and more.

Pickle did not charge for the 300 ounces she gave to another local mother, she said. Although she understands why others sell, her focus is to help alleviate the stress of caring for a newborn.

“Being a mom to a newborn is hard… I’d love to give back,” Pickle, 32, said. “I’d rather donate because I can.”

As a mother of two, she’s donated informally online and formally to the Mothers’ Milk Bank of North Texas after both births, she said. After having her first child, Pickle provided her extra supply to an adoptive mother who she found on Facebook for about six months. Seeing the mother’s Facebook page with pictures of the child and the activities they would do together made Pickle feel comfortable about connecting with someone who was a stranger at the time, she said.

“Most of the times I’ve donated to local moms, they’ve offered to come pick it up at my house. Then I’ll have my husband with me or my mom, just in case. You never know,” Pickle said. “After that first meeting when (the adoptive mother and baby) came to my house, then I was comfortable with meeting up other places or meeting up at their house to give it to them.”

Although Pickle has passed a medical screening and blood test to donate to the milk bank, which she can use to show other mothers that she’s in good health, she acknowledges that she would be hesitant to buy another person’s breast milk online if the roles were reversed.

“You really don’t know what’s happening in those peoples’ lives (and) how they’re handling the milk,” she said. “I am a pretty trusting person, but I don’t know — with Facebook Marketplace or Facebook in general, I do tend to be a little bit more skeptical.”

Shaye Reeves, a mother who received Pickle’s milk to give to her 2-month-old daughter, recently discovered the world of online milk sharing through her neighbors, she said. Her daughter was born with tongue-tie, a condition that restricts the tongue’s range of motion and can affect the way a baby eats and swallows, which made it difficult for Reeves to breastfeed. Although she pumps, she is only able to produce about 10 milliliters per pumping session while her daughter eats about 3½ ounces for each feed, she said.

“I literally only make a small appetizer for her,” Reeves, 34, of Haslet, said. “I’ve legitimately tried probably about 15 different formulas, and she just won’t take them…. So I have to really rely on donor breast milk for my daughter to eat and thrive.”

Reeves only obtains donor milk from people who also donate to the local milk bank and can show their lab work, such as Pickle. She’s connected with eight donors total, she said, and most have either donated or traded it for supplies such as breast pumps or storage bags. One donor charged Reeves about $80 for 200 ounces, or 40 cents per ounce.

Reeves wishes that more people understood the difficulties behind breastfeeding and how it can be a time-consuming task that requires support from family or loved ones to stick with on a consistent basis, especially when an older child needs to be supervised during a pumping or feeding session.

“Breastfeeding is a lot of work, and the women that can do it and overproduce and be able to donate are incredible human beings,” Reeves said. “I think it’s a beautiful thing.”

Risks of informal sharing and reach of milk banks

Medical experts and organizations such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration advise against feeding infants breast milk that’s been acquired online or directly from another person. Risks of this practice include exposure to infectious diseases, illegal drugs and certain prescription medications. Additionally, human milk that’s been stored improperly can cause it to become contaminated.

Ideally, parents who overproduce are encouraged to donate their milk to a local milk bank if one is accessible to them.

The Mothers’ Milk Bank of North Texas, based in Benbrook, is one of 33 banks in North America. Donors must be tested for HIV-1 and HIV-2, hepatitis B and C, syphilis and more to be eligible to donate their milk, according to Amy Trotter, community relations director. They receive no compensation for the milk they provide, and they can drop off their milk at one of 50 collection sites across North Texas or schedule it to be picked up at home.

In 2023, the North Texas bank dispensed almost 830,000 ounces from about 1,200 donors, prioritizing vulnerable infants, she said. Since 2020, its monthly dispensation numbers for January have steadily increased by about 10,000 ounces each year.

The bank dispenses 70% of its pasteurized, tested milk to babies in local neonatal intensive care units (NICUs), and the remaining 30% to outpatient babies, some who are medically in need with a doctor’s prescription and some who are healthy but have access to it only during their first two weeks of life, Trotter said.

This leaves parents who simply are unable to produce enough independently, who have medical complications that impact their milk production, or who have infants that refuse formula, in a limbo.

“We do kind of have parameters on who receives the milk because we are first serving a very fragile population, and that is our mission as a nonprofit,” Trotter said. “What our donor moms always like to hear is that one ounce of their milk can provide three feedings for a micro-preemie baby. If they’re donating a minimum of 100 ounces, that could potentially be 300 feedings.”

Micro-preemie babies are born before week 26 of pregnancy or weigh less than 28 ounces, according to Cook Children’s Health Care System.

Dr. Lisa Stellwagen, a clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of California San Diego and president-elect of the Human Milk Banking Association of North America, noted that the medical necessity for donor milk focuses on the prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis, a serious gastrointestinal illness that typically affects premature babies and has a mortality rate as high as 50%.

“That’s the reason milk banks exist,” she said.

Stellwagen said that the availability to provide milk to a child who is sick at home rather than the hospital varies by region. But overall, accessibility to the remaining parents searching for tested, pasteurized breast milk — along with mitigating the practice of online exchanges — will require more donors to step up, milk bank infrastructure to be improved, and education of the issue to be more widely shared.

“There’s just a huge distribution problem,” she said. “There’s enough milk, we just haven’t gotten the word out. Not everybody is aware of milk donation. A lot of people have never heard of the milk bank… One of the concerns we have in the (Human Milk Banking Association of North America) realm is just increasing the capacity so that we can provide donor milk to families at home because there’s a lot of interest in that and avoiding formula.”

Obstacles with breastfeeding; Breast milk demand

A notable hurdle mothers can face with breastfeeding is maternal age, Stellwagen said. The human body is designed to have children between the ages of 14 and 25, she said, but people are waiting longer to give birth in modern times.

From 1990 to 2019, the fertility rates of women ages 20-24 decreased by 43%, and those of women ages 35-39 increased by 67%, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Additionally, the rate of women ages 40 and older giving birth for the first time has doubled over the past 30 years, according to the University of South Carolina Arnold School of Public Health.

In addition to maternal age, other health issues such as obesity, diabetes and hypertension can contribute to issues with milk supply, Stellwagen added.

“It really depends on who you are,” she said. “Evolution put a ton of energy into developing breast milk because it was the only way our species has survived all these years. I like putting a positive spin on it: Most people do fine with support and good maternal health and should make a full, robust milk supply for their child.”

In general, prioritizing breast milk over formula is valid, as the health benefits it provides outpaces the risks associated with formula, Stellwagen said.

“Children do fine on formula, but there are risks associated with it. Risks of being overweight. An increased risk of sudden infant death syndrome. A doubling in the risk of many common childhood infections” like ear infections, diarrheal illness and respiratory illness, she said.

Kandace Espinosa, an administrator for the Dallas-Fort Worth Facebook group, said the group was created after the formula shortage crisis hit in late 2021 and was exacerbated in February 2022 by Abbott Nutrition’s recall, which halted production after inspectors found potentially dangerous bacteria. This caused the demand for breast milk to surge.

Espinosa and other administrators vet profiles to the best of their ability and require members to answer survey questions and follow a specific format when advertising their milk through posts.

“We no longer accept profiles that are less than one year old. We vet the rest of their profiles, groups they’re part of and ensure they answer all the group questions to our satisfaction before even allowing them in the group,” she said. “We are transparent and do our best to eliminate possible scammers and dishonest people.”

Espinosa always encourages parents to ask for lab work or be willing to pay for those tests, while referring to the North Texas milk bank as a primary resource, she said. Among notable examples of exchanges she’s witnessed in the group include a surrogate donating to another mother with cancer who was unable to nurse, as the parents of the surrogate’s baby did not want the breast milk.

“Risks are there, but there’s also a big benefit. For many, it is worth taking,” she said.

Stellwagen recommends parents to first seek help from their child’s medical provider or a lactation specialist in their community when they encounter obstacles with breastfeeding.

The North Texas milk bank offers a free breastfeeding support program hosted by certified lactation consultants every Tuesday from 10 a.m. to noon at its Benbrook location and offers online sessions every second and fourth Thursday from 6 to 8 p.m.