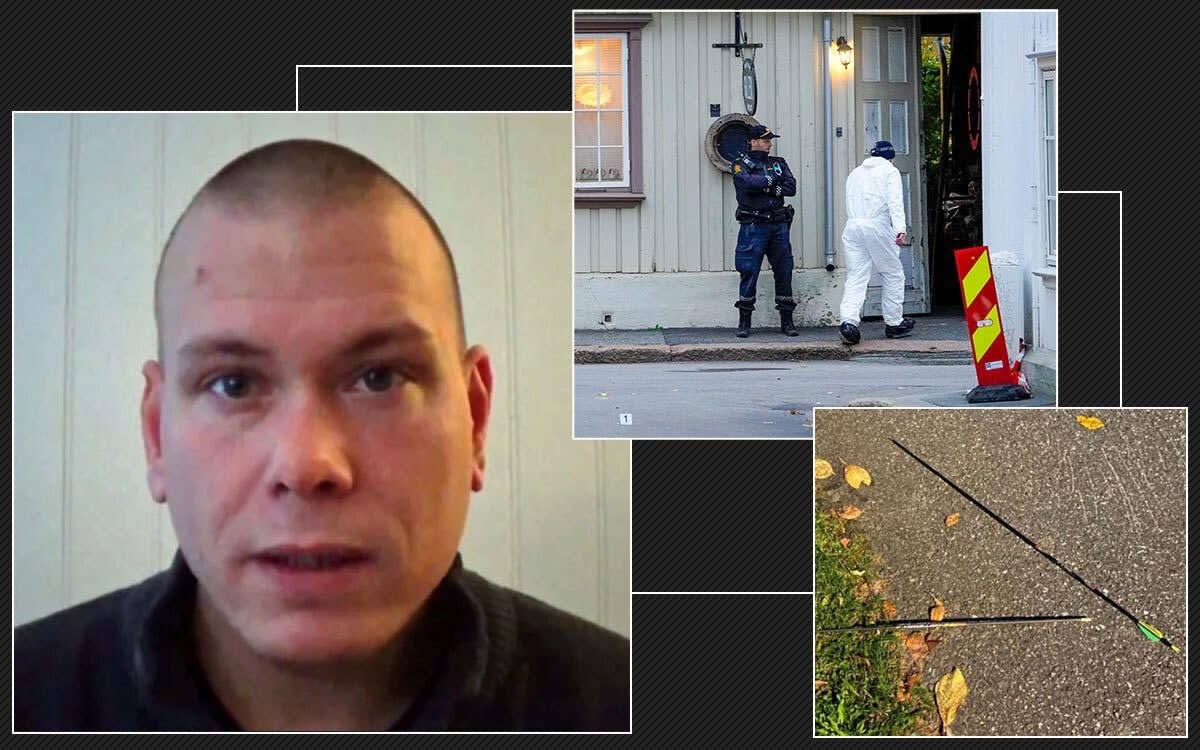

How the Norway attack plays into the legacy of Anders Breivik

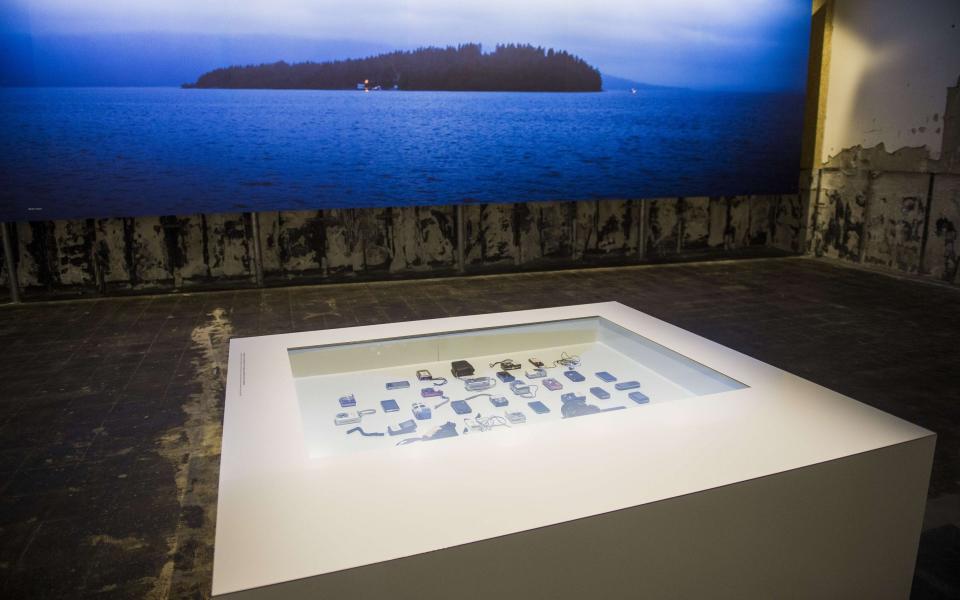

Before the Norwegian far-Right terrorist Anders Behring Breivik launched his gun rampage on the island of Utoya in the summer of 2011, he outlined two goals in his sprawling, incoherent manifesto.

By attacking a Labour party youth camp, he hoped to kill the party's future leaders and so slow the mass migration of Muslims into Norway he believed the party had engineered in a secret "Eurabia" conspiracy.

And he hoped to provoke an overreaction against the anti-migration right which would force them to follow his path to militancy.

Neither of these things happened.

The country's new Labour government – whose members were announced on Thursday in the wake of Wednesday's bow-and-arrow terror attack – contains two ministers who survived Utoya.

In the words of incoming prime minister Jonas Gahr Store, they are "carrying this past with them".

Moreover, rather than being repressed, populist, anti-migration parties have thrived.

Migration and refugee concerns

Two years after his attack, the populist Progress party, for which Breivik was a youth activist, entered government for the first time and remained as a junior coalition partner in Norway until last year.

The Danish People's Party saw its best election result ever in the years after his attack, becoming the second biggest party in parliament, and the populist Sweden Democrat party got nearly 18 per cent of the vote in 2018.

Populist success was helped by the refugee wave of 2015, which strengthened public concern over migration, while the parties have also been helped by the failure of integration policies.

Sweden, in particular, has suffered a surge in the number of shootings and explosion attacks carried out by first and second-generation immigrants, with gun homicide rates rising to among the highest in Europe.

There have been sporadic Islamic terror attacks: the Copenhagen shootings of 2015, which claimed two victims, and the Stockholm truck terror attack of 2017, which saw seven killed.

Burqa bans

While Scandinavia has come nowhere close to the war of civilisations of Breivik's diseased fantasy, public attitudes have hardened, with public policy moving in a direction of which Breivik would approve.

Both Denmark and Norway brought in burqa bans in 2018, Denmark in all public places and Norway at schools and universities. Denmark's fringe Stram Kurs party even wants Islam banned and all Muslims deported.

In Sweden, both the populist Sweden Democrats and the Moderate Party have at a municipal level have brought in school burqa bans, bans on halal food in schools, and even a ban on praying at work.

Rhetoric has also toughened, with even Denmark's Social Democrats now ruing the problems caused by "non-Western immigration" and seeking to reduce the share of “non-Westerners” in all disadvantaged neighbourhoods to just 30 per cent.

Sweden has been the country where anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies has taken the least hold on politics, but there are signs of a shift even there.

Magdalena Andersson, who is likely to become the country's first female prime minister next month, is pushing to make it much tougher for unskilled workers to migrate to the country, and is increasingly criticising the problems caused by "large groups which have come from non-European countries with a weak tradition of education".

It is hard to foresee exactly how these hardening Scandinavian attitudes towards Islam and migration will be affected by a suspected terror attack carried out by Muslim convert in Norway.

But it is unlikely to make them any more positive.