Not in my backyard: Metro Phoenix needs housing, but new apartments face angry opposition

NIMBY-ism in the Valley:

Not in my backyard| There, not here| Rezoning hurdles| Targeting City Hall | What needs to change?

Angry rural residents brought farm animals to protest apartments planned near the semiconductor plant being built in northwest Phoenix when they attended a neighborhood meeting in April.

In Chandler, people unhappy about an affordable apartment project filled a high school assembly room in January 2023, booed the developer and accused him of lying about traffic and school crowding.

Residents living near proposed apartments by a Scottsdale hospital that would have given a 10% rent discount to nurses, firefighters and police officers fought the project in 2022, saying four stories would block their views, and there wasn’t enough water.

After the Surprise City Council approved an affordable complex in August 2022, neighbors who protested it because “it didn’t fit in” sued as part of an effort to give voters a chance to cast a ballot on the complex's future.

In Buckeye, apartment plans were scrapped in 2021 after residents mounted a big opposition campaign saying rentals would increase crime and bring down property values.

Affordable apartments and high-density housing have become fighting words in metro Phoenix as the much-needed homes draw more opposition than ever.

The opposition often labeled “not in my backyard” — or NIMBYism — has stalled tens of thousands of rental homes, as metro Phoenix faces a housing shortage that’s pushed up rents beyond what most residents can afford and led to a record number of people becoming homeless.

Economists, growth analysts and housing advocates say the housing shortage and problems getting more homes built could break Arizona’s economy. Developers and city officials are bracing for the next round of apartment zoning fights in 2024.

Affordable housing drove economic expansion

Most people fighting rental housing cite rising crime, falling home values, traffic problems, overcrowded schools and lost views as their reasons for not wanting apartments near them. Many acknowledge the Valley needs more housing, particularly for people making middle- and lower-income wages, including teachers, police and service workers.

But most are OK with having the rentals in other neighborhoods or obtaining upgrades and more amenities for neighborhoods from the developer. People who oppose developments prefer the QIMBY label, "quality in my backyard."

“I don’t like the NIMBYism term,” said Lisa Perez, a neighborhood activist and member of the Phoenix Planning Commission, which reviews and approves zoning change requests. “It’s not that I don’t want development in my backyard. I want good development.”

She said the public deserves a right to have a voice in the development of their cities.

The fights have slowed down an already arduous zoning and city approval process that can take Phoenix-area developers as long as four years to get an apartment complex built.

The zoning battles have also put City Council members in the hot seat with unhappy neighbors who can use their votes to get them out of office.

“Even getting one affordable apartment project built is almost seeming impossible in the Valley,” said Mark Stapp, growth expert and director of the Master of Real Estate Development program at Arizona State University. “And because we can’t keep up with demand, the ability to afford a place to live on a typical salary is eroding.”

He said relatively affordable rents and home prices were the “goose that laid the golden egg” for metro Phoenix’s growth, and the area is losing that.

“Our housing affordability and availability must be a top issue for elected officials, city planners and the development community because the issue will hurt our economy as companies decide not to expand or move here because employees can’t find or afford housing,” Stapp said.

'Economy will die': Low housing supply slows growth

Arizona needs 100,000 to 250,000 more homes — depending on who’s tracking and how — to ease the historic housing shortage. Most of the dearth is in the Phoenix area due to slower building and significant population growth.

Restaurant and retail workers can’t afford to rent in any of the Valley’s 11 largest cities, according to an analysis from Elliott D. Pollack & Co., an economic and real estate consulting firm. Firefighters can only afford rent in four of the cities tracked, while elementary school teachers and construction workers can only afford to live in three of the cities.

The number of metro Phoenix apartments with rents below $1,000 has plummeted 86% since 2010, according to new data from the Maricopa Association of Governments.

“This housing shortage is the biggest economic threat I have seen in the 53 years I have been an Arizona economist,” Elliott Pollack said. “Current policies are keeping supply artificially low, and if we stay on the road we are on, the economy will die.”

Most land in Maricopa County must be rezoned to allow for rental homes, and the process has never been as difficult and time-consuming as it has been during the past few years, according to developers.

About 1.4 million acres of metro Phoenix vacant land are zoned for residential development, but only 52,000 acres are zoned for multifamily.

At least 25,000 apartments have been planned but not built during the past decade due to NIMBYism and zoning fights, estimated Michael Lieb, a veteran Valley real estate broker and developer.

He and other developers said tracking how many rental projects don’t make it through the planning and zoning process is difficult. That’s because early opposition from neighbors and planners stops some planned developments from ever making it to the application process.

Groups form to counter apartment opposition

Clay Richardson, managing partner of Phoenix-based multifamily builder Wood Partners, said, “Half of the projects I have developed in the past several years wouldn’t be viable today. I wouldn’t even try to get them through the planning and zoning process.”

He said neighbors’ fear of the unknown is driving opposition and estimated delaying a project can cost up to $10,000 a day.

Affordable housing developer Dominium has encountered big opposition campaigns against apartment projects in Buckeye, Chandler and Surprise over the past few years.

Owen Metz, senior vice president at Dominium, said planning, neighborhood outreach and research — including a traffic study — for its Chandler project cost $1 million before it bought the land. The project, which was the focus of contentious community meetings last year at Hamilton High School in January and November, still hasn't been approved.

After the January meeting, the developer nearly halved the number of apartments at the complex — now called Sonoran Landings — and made it for residents 55 and older to cut back on traffic and any potential school crowding. Dominium is also planning two light industrial buildings on part of the site to bring jobs to the area, per Chandler's general plan.

All were issues neighbors angrily brought up in January.

At the November meeting with neighbors about changes to the plan, Metz apologized for the gathering near the start of the year. The number of neighbors to show was much fewer than in January, but most still weren't happy with the changes.

One resident used the microphone to tell the developer to build the apartments in Phoenix because the neighborhood didn't need the prostitution, drugs and crime that such a complex would bring in the East Valley city.

Dominium also had to pay to fight a lawsuit on its Surprise project.

Stephanie Duarte, who lives next to a new Dominium apartment complex called Vista Ridge that opened in south Phoenix in late October 2023, said she looked at apartment complexes in the area similar to the new affordable one, and they cost twice as much to rent.

"The apartments are not only affordable but offer luxury features for renters," Duarte said. "We need more housing like it that gives renters dignity and pride about where they live. The apartments are a great addition to our neighborhood."

Housing advocates, business leaders and government officials are taking on the rising problem of community opposition and trying to dispel myths about rentals.

Several groups, including Home Matters, are trying to refocus the conversation with a new movement called Home Is Where It All Starts. The goal is to provide information to help alleviate and counter arguments made by future neighbors of planned housing complexes.

“Why should we care? Individuals in our community are suffering,” said Nico Howard, the past chair of the Phoenix Planning and Zoning Commission, who joined Lieb to start the group Home Arizona to combat the state’s housing shortage. “A single mother making $60,000 a year who can’t afford to live in the city where she works suffers long commutes and more time away from her family.

“If a large portion of your labor force can’t live close to where they work, it becomes really difficult for employers to retain employees,” he said.

Apartment plans spur fights across metro Phoenix

Neighbors opposing apartments are turning out in droves for meetings to fight multifamily developments they believe will harm their areas. Increasingly, they are mounting prolific letter-writing campaigns to their city governments to stop them.

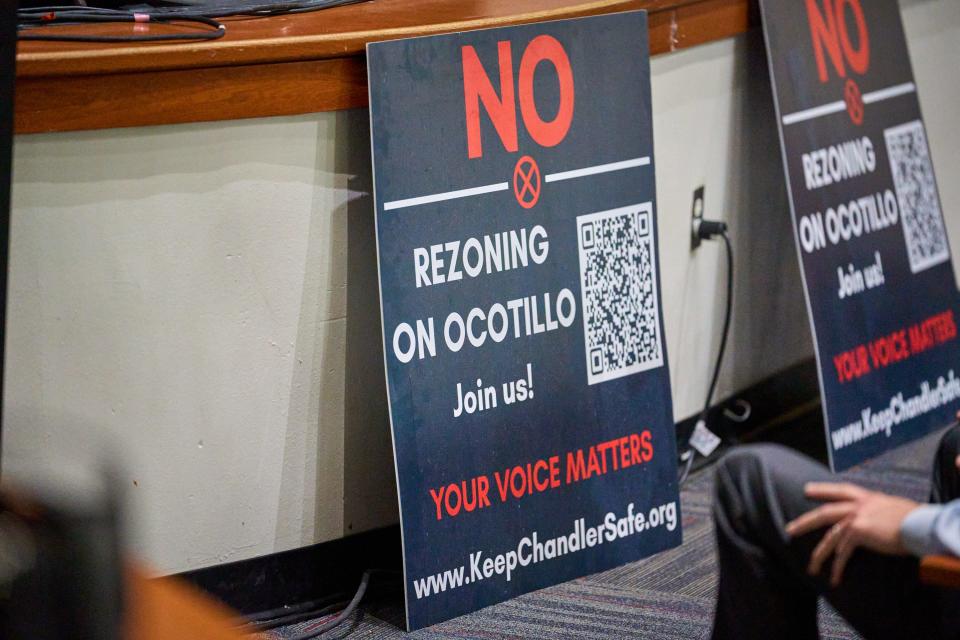

Organized groups go door to door, gathering signatures and encouraging other neighbors to send protest messages to their City Councils and show up at meetings with developers.

Neighborhood action groups from different parts of metro Phoenix are also supporting each other.

Here are a few of the multifamily developments that have spurred opposition recently.

Advocating for 'buffers' in Phoenix

Neighbors brought burros and wore T-shirts saying “one per acre” — meaning one home per acre — to a meeting with the developer in April 2023.

“I can’t believe this development is even being considered,” said Diane Habener, a neighbor of the 226-unit Phoenix apartment complex planned at 17th Avenue and Happy Valley Road near the under-construction Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company facility, to the Phoenix Planning Commission in early May 2023.

“There’s only one parcel between me and this development, and I have horses,” she said about her 2.5-acre ranch. “Traffic is now unbelievable in the area. There are a lot of other places where high-density apartments can go.

“I came here from California, where there are buffers between developments. Don’t put a high-rise next to rural homes,” she said about the planned three- to five-story apartments.

The Phoenix Planning Commission passed the zoning application narrowly in early May 2023, saying they understood the residents’ concerns, but housing was needed.

Perez, the community activist and Planning Commission member, voted against the Phoenix apartments near the semiconductor plant partly because of traffic issues.

Emotions run high over Chandler project

At a tense meeting in late January 2023 for Dominium’s Chandler project, about 150 people showed up to mostly object to 500 affordable apartments. Protesters, many with the opposition group Voice of Chandler, booed the developer, read from prepared handouts and yelled “Don’t lie” when the developer and traffic consultant spoke.

Several people called the apartments with below-market rents Section 8 housing, which has a negative reputation because a component of that federal housing assistance program that supported building apartment complexes ended up segregating people with low incomes into one area. But that aspect of the Section 8 program hasn't been used for decades to build affordable homes.

“There’s a lot of emotion involved with any new development coming to a community. Developers and zoning attorneys are trying to address those concerns and work with the neighbors early on,” said Tom Bilsten, who is hired by developers to go door-to-door to talk to neighbors about new projects. “We want to try to eliminate the fear of the unknown, even if the neighbor still disagrees with the development.”

He said Dominium's Chandler project unexpectedly drew more anger from neighbors than any project he has worked on.

Scottsdale council votes down 273-unit complex

Neighbors of the proposed Mercado Courtyard apartment development with 273 units at Shea Boulevard and 92nd Street wanted to know what the discounted rents would be for first responders and service workers and disputed they would be affordable for those groups.

Many also didn’t like the design or how big the parking garage would be. Some said they would back the project if the homes were for sale.

Scottsdale is considered one of the toughest Valley cities to get affordable rentals approved.

Anti-urbanization group Protect Scottsdale posted a video about what the group called "tricks" developers use to get projects rezoned, including placing hearing signs so people can’t read them as they drive by and holding meetings with neighbors in the summer when people are on vacation.

Despite passing the Scottsdale Planning Commission, the City Council voted down the Mercado Courtyard rezoning application in December 2022.

Threats to move out if rentals built in Buckeye

Dominium’s proposed 300-unit Buckeye apartment project at Thomas Road and 195th Avenue got voted down after neighbors barraged the City Council with complaints.

One resident who lived near the development told Buckeye Councilmember Clay Goodman his neighbors were discussing moving out if the apartments were built.

“It's a little scary sometimes, and a little sad,” said Metz, the Dominium senior vice president, about some reasons behind protesting apartments. “It’s about a fear of bringing housing and people the neighbors don’t want into their community.”

Going to court over apartments in Surprise

In Surprise, a community group — a forerunner to Voice of Chandler called Voice of Surprise — sought a voter referendum after the City Council's approval of a mixed-use development with apartments Dominium wants to build at the southwest corner of Cotton Lane and Waddell Road.

The city clerk's rejection of the group's referendum attempt led to a lawsuit. In August 2023, the Arizona Supreme Court ruled in Voice of Surprise's favor, saying the clerk overstepped that office's authority. The litigation is ongoing.

“NIMBYism is happening. People are scared about who might live next to them,” said real estate attorney Manjula Vaz of Gammage & Burnham, the law firm that represented Dominium in the case. “Affordable multifamily brings a lot more diversity to an area, and we need to want that.”

Legislative proposal on housing opposed by cities

To try to tackle Arizona’s housing shortage, a legislative committee was created in 2022. Some of the group’s recommendations were included in a controversial bill introduced in early 2023 by state Sen. Steve Kaiser, R-Phoenix, who was co-chair of the study group.

Initially, the legislation called for taking much of zoning control from municipalities, which drew strong opposition.

Cities saw the bill taking away their local power to decide on developments and fought it.

The legislation was redrafted several times but still ultimately failed. Kaiser resigned as a state senator shortly after the bill died, though he said it wasn't because of the legislation stalling.

“Multifamily development is trying to short-circuit the local planning process by going to the Legislature, and that’s dangerous,” said Scottsdale Mayor David Ortega about the bill. “Cities are receiving a frontal attack on our type of living, and it’s causing conservative elements to push back.”

César Chávez, a former state representative from Phoenix who co-chaired the housing supply committee, said, “Fixing Arizona’s housing shortage is a big lift, and I am afraid the political will is not there. It’s a polarizing conversation.”

Chávez lost his Democratic primary race in 2022 and is no longer in the Legislature.

“Today, the zoning process is a mess,” said Paul Johnson, a developer and former Phoenix mayor. “It’s the worst I have ever seen it. We need to fix the process, but it won’t be fixed at the Legislature.”

Alan Stephenson, deputy Phoenix city manager and former planning and development director, said there’s not one solution to the problem because, besides zoning, there’s a labor shortage and state laws and other requirements that cause delays in development approvals.

Arizona growth expert Steve Betts, who is managing director of development for Holualoa Cos., didn’t support the legislation but said something has to change in cities' zoning processes. Otherwise, he said, similar or even worse changes will be proposed in 2024.

The political implications of housing fights

City Council members and planners often get angry and even threatening emails and calls from neighbors about developments they don’t want near them.

One email on a Phoenix mixed-used project with apartments called a City Council member a Nazi, and another accused a City Council member of taking bribes.

Mesa Councilmember Julie Spilsbury had several controversial apartment projects come up for a vote in her district in 2022.

“My constituents are more than that. They are the people I raised my kids with, who I go to church with and who live less than a mile from my home,” she said. “So, when they are screaming at me because they don’t want apartments near them, and they don’t want ‘those people’ living near them, it’s extremely hard. I cried a lot."

But she backed the projects, including one near a hospital and employment centers that Spilsbury said got pushback from a city agency. The Mesa City Council approved them all.

Those complexes will bring more than 1,000 homes to Mesa and include the Countryside Modern, Emblem at Mesa, Villas on Main and Millennium at Superstition Springs complexes.

Home Arizona was created to help educate politicians and give them backing when neighbors start threatening their political standing, said Howard, the Phoenix Planning and Zoning Commission chair.

Johnson, the former Phoenix mayor, thinks there’s a change coming with voters.

“A growing group of people, many of them younger, are realizing housing is out of reach for them. They can’t afford to live close to their parents or in communities where they grew up,” he said. “They are upset and understand the connection between there not being enough housing and the actions City Councils are taking. They will vote.”

Continue suburban sprawl or 'grow inward'?

Growth advocates say the word "density" has become a trigger and often shuts down development discussions before they start.

“When you talk about density, people's antennas go up, and they get concerned,” said Christopher Ptomey, executive director at Terwilliger Center for Housing at the Urban Land Institute. “It's a growing problem.”

Betts said density has become a bad word, but it’s an economic issue.

“We have this great tidal wave of jobs coming, but we need to find homes for the new residents coming to fill them,” he said. “You can cause more problems by putting all the new housing out on the fringes — or grow inward with more density.”

Republic reporter Kunle Falayi contributed to this article.

Reach the reporter at catherine.reagor@arizonarepublic.com or 602-444-8040. Follow her on X, formerly Twitter: @CatherineReagor.

Next up:

Phoenix-area affordable housing projects often face wall of opposition

Sasha Hupka

Arizona Republic

The line of people waiting to take the microphone stretched to the back of the auditorium at Hamilton High School in Chandler.

In theory, the event was supposed to provide a forum for community members to ask questions of officials with Dominium, the developer of an affordable housing project proposed on an island of county land in south Chandler.

But the late-January event last year was too little, too late.

Months after talk of the development first erupted in the community, most of the speakers had comments instead.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: The Phoenix area needs more housing. But more are saying, 'Not here'