It's not just Britney Spears: 1.3M Americans are under conservatorships. Activists want reform.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Sheila Owens-Collins hoped her ailing mother, Hattie Owens, would spend the last years of her life as she wished, as a retired schoolteacher living on her own in a spacious house in Houston, active in her church and community center.

“She envisioned her life at home, tutoring students and having kids coming over to swim in the pool or spend the holidays,” said Owens-Collins, a pediatrician in Rockville, Maryland. “Her biggest wish was never having to leave home.”

Instead, Owens was placed under a court-appointed guardianship after what Owens-Collins claims were a relative's attempts to gain access to Owens' finances through legal chicanery while her mother was hospitalized and under temporary guardianship.

"She never came out of it," Owens-Collins said.

Cut off from her regular stream of visitors, Owens’ health deteriorated and she died in court custody in 2019.

'I wouldn’t be surprised if there are reforms': Will Britney Spears' dramatic testimony affect other cases, laws on conservatorship?

The case illustrates what elder and disability justice advocates say is a flawed system of guardianship in dire need of an overhaul. The debate over this kind of oversight, also called conservatorship, has drawn renewed attention with recent publicity surrounding pop star Britney Spears and prompted new action from lawmakers.

“It’s a predatory system, geared to isolate people from their families, separate them from their estates and take away all their privileges,” said Owens-Collins, 69. “They’re isolated and neglected.”

Advocates for the disabled, elderly and others hope that increased public awareness of problems surrounding such arrangements can help nudge forward the reforms they’ve been seeking for years.

An estimated 1.3. million Americans are under guardianship, according to the AARP, arrangements that, depending on which state they live in, can determine their abilities to purchase diapers or cast a ballot, among many other limitations.

Guardians, appointed to manage affairs of individuals deemed unable to responsibly make their own decisions, can be family members, attorneys or agency professionals. While their purpose is to help individuals live lives driven as much as possible by the individual’s own choices, such arrangements can be exploited for personal gain without proper oversight, said Nina Kohn, a law professor at New York’s Syracuse University who specializes in elder law.

"Advocates have known for decades that our guardianship system is deeply flawed," Kohn said.

She and other legal experts said guardianships are too often needlessly prescribed, overly restrictive and too difficult to get out of. Meanwhile, they said, guardians are both inadequately vetted and monitored by states that lack the will or resources to do so – leaving their wards, and those individuals’ estates, subject to victimization.

Opinion: Conservatorships trampled Indigenous rights long before Britney

“It’s really invasive," said attorney Zoe Brennan-Krohn of the ACLU's disability rights program. "People with disabilities, or people perceived to have disabilities, are stripped of their civil liberties – their right to make choices, to decide where to live, where to work, how to spend the money and who they’ll see."

Cases are often decided behind closed doors, some without the affected individual’s input.

Jasmine Harris, a professor of law at the University of Pennsylvania, said many guardianship hearings and documents are off-limits to the public and media out of medical privacy concerns, resulting in not just a lack of information but the harm of “not allowing the public a window into this process of contesting legal capacity, of contesting norms of disability and what it means to be a person with a disability in society. “

Roughly 61 million adults in the United States, or about one in four, lives with a disability, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

While some guardianships can be useful measures, advocates say courts are too quick to impose plenary guardianships that strip individuals of most of their rights by giving guardians full decision-making authority. These arrangements represent the vast majority of all guardianships, which, when needlessly applied, can negatively impact individuals’ physical and mental health, said Jonathan Martinis, senior director for law and policy at the Burton Blatt Institute at Syracuse University in New York.

Because guardianship can take away people's power to make decisions about their own lives, said Robert Dinerstein, director of the Disability Rights Law Clinic at American University in Washington D.C., "it has been called a form of 'civil death.'”

That’s what Owens-Collins said happened with her mother, who she said had entrusted Owens-Collins with power of attorney until it was wrested away. Her mother was denied health procedures, such as cardiac rehabilitation, that Owens-Collins said had been medically recommended. She also had to relinquish her phone.

“They take your civil rights away from you,” Owens-Collins said. “She always called me for advice but I had to go through her guardian to get it done. She had no choice. She was so isolated and depressed.”

People in guardianships treated 'as less fully human'

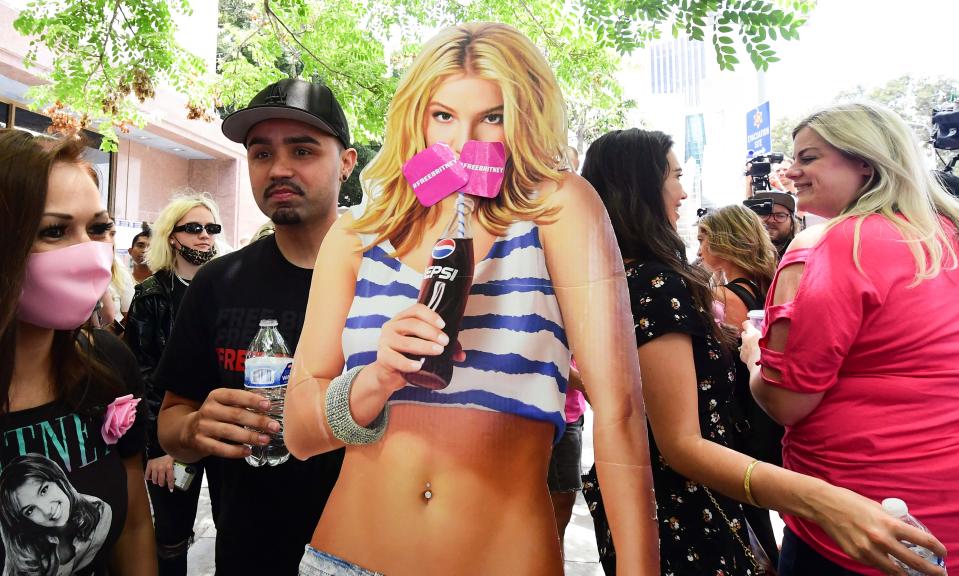

Guardianship issues most recently have been brought to light by the case of pop star Spears, who has been fighting to end the California conservatorship that since 2008 had been controlled by her father, James “Jamie” Spears. Last week, the elder Spears abdicated his role as guardian as a judge ordered him to turn over the singer’s estimated $60 million in assets to a temporary conservator.

“Every several years there’s a situation that brings attention and scrutiny on how guardianship is done, but then there’s a return to a lack of commitment and resources,” said Terry Hammond, executive director of the Texas Guardianship Association. “It takes a high-profile situation to make incremental progress.”

In past years, similar disputes have swirled around guardianships involving other prominent people, including civil rights activist Rosa Parks, musician Brian Wilson and comedian Groucho Marx.

Those under such arrangements range from older adults with cognitive conditions, such as dementia, to young adults with intellectual or developmental disabilities. Policies vary from state to state, and even county by county – but there has been little effort to keep a full accounting of how many exist.

Britney Spears' dad is out: How quickly could her conservatorship end now?

That lack of data about how many guardianships there are is telling, Brennan-Krohn said.

“We as a society keep track of things that are important to us and things we think matter,” she said. “I think it’s striking that this is something that historically we have not thought was important enough to keep track of.”

Last week, Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, and Bob Casey, D-Pennsylvania, introduced a bipartisan bill that would increase federal grants to help states create guardian registries to facilitate sharing of background-check information. The National Guardianship Act would also create a national resource center that would, among other things, promote less restrictive guardianship practices and collect and develop guardian training materials and model legislation.

“We found that once a guardianship is imposed, there are few safeguards in place to protect against unscrupulous individuals who abuse their responsibilities," Collins said.

Brennan-Krohn said conservatorships are an outgrowth of the historic institutionalization of people with certain disabilities based on similar underlying presumptions about their decision-making abilities.

“It’s treating those people as less fully human, as less deserving of the autonomy to have their decisions taken seriously,” she said.

Proposed reforms have support - but states slow to enact them

Kohn, who specializes in elder law, said policymakers have shown little interest in making systemic changes.

“Too often when scandals are reported or concerns are raised, the legislative response, if any, is to impose new penalties on bad actors rather than adopting reforms that would change the underlying system,” Kohn said.

One reform measure gaining steam is supported decision-making, which allows disabled individuals to maintain authority over life choices by selecting trusted people to advise those decisions. The first person to win that legal right was Jenny Hatch, a Virginia woman with Down syndrome whose 2013 Virginia court case ruling gave her the legal right to make decisions over her own life with support from friends.

“We know that people who have more control over their lives – more self-determination – have better lives," said Martinis of Syracuse University, who represented Hatch in that case.

So far, at least 13 states have moved to allow consideration of supported decision-making practices prior to guardianship.

“It doesn’t require any involvement from the court,” Brennan-Krohn said. “It doesn’t require walking into a courtroom or getting the government into your life.”

Such options, she said, should be made more available “so more people just avoid going down that guardianship path at all.”

The Uniform Law Commission, which develops laws that individual states can adopt, has developed model legislation for systemic guardianship reform that few states so far have enacted, despite broad support.

“One of the reasons states have been slow… is that they don’t want to spend any money to do so,” said Kohn, the principal drafter of the legislation. “It’s cheaper and easier to criticize bad guardians and impose new penalties. But it won’t fix the underlying problem.”

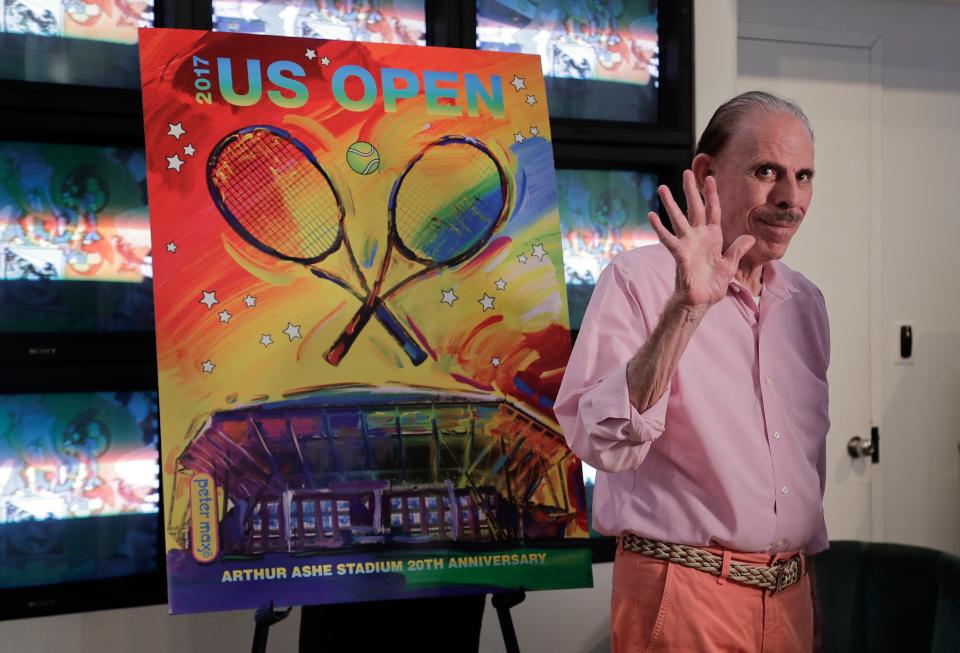

Sometimes, the fight is left to the families, as in the case of Libra Max, daughter of renowned German American painter and Holocaust survivor Peter Max, whose guardianship she has been trying to terminate since 2019.

Originally, the 83-year-old Max, who has dementia, was placed under guardianship in 2016 due to alleged mistreatment by his now-deceased wife.

A succession of guardians followed, and when a third was appointed in June 2019, Libra Max said, “the nightmare began.”

The older Max was given a new cell phone without any phone numbers. His children were banned from the family home. They got rid of his beloved pets. Suddenly, without explanation, Libra Max was told she could only see her father three times a week for an hour on a public park bench.

The appointed conservator also began charging thousands of dollars in exorbitant fees, she said, and COVID-19 only made the situation worse.

“It has been the most heartbreaking experience in my life," Max said. "My father begs me, he begs his friends on Facetime, that he wants to be with us.

“This happens to our elderly, it happens to people with disabilities and it's a form of human trafficking,” she said.

The ACLU's Brennan-Krohn said the system needs more guardrails, “the way we do in the criminal legal system where we have protections so that people don’t end up in jail just because they’re poor or don’t understand what’s happening. We need to recognize guardianship as the really big deal that it is.”

The awareness raised by the Britney Spears case, she and others said, offers an opportunity to make progress.

“This has for a long time existed in the shadows,” Brennan-Krohn said. “I’m hoping this is really the beginning of a sea change in how we think about and support people with disabilities.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: #FreeBritney: Conservatorships need reform, activists say