It's not just schools — book banning is also increasing in prisons

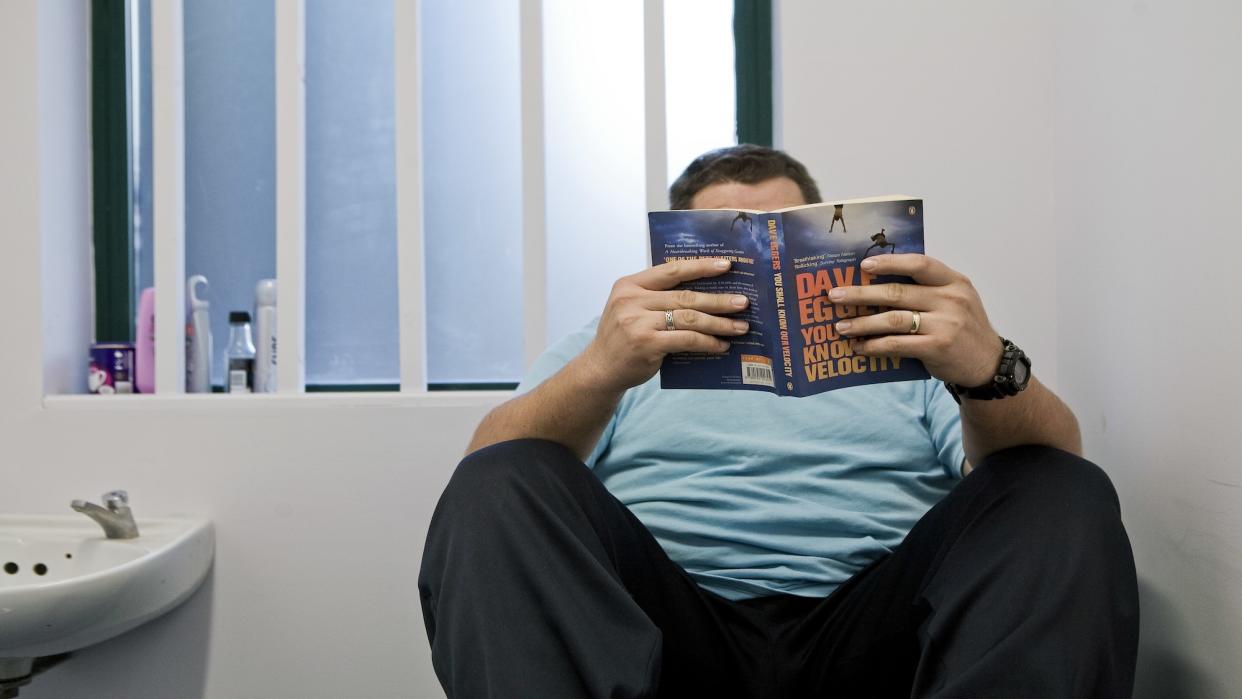

In a renewed era of book banning, most of the news cycle has been dominated by efforts — mostly by conservative groups — to ban certain books from school libraries. However, a new report has found that the issue of pervasive book banning has now spread to an unlikely locale: American prisons.

The report, titled "Reading Between the Bars," was published on Oct. 25 by PEN America, a literature and writing advocacy group. This report concluded that "carceral censorship is the most pervasive form of censorship in the United States." It noted that both the Federal Bureau of Prisons and state correctional departments censor books, "and the rationales they employ for censoring books are vast and varied."

And unlike in schools, a book in prison may be censored "not [for] its content but a host of other factors," even down to its physical appearance, according to the report. Given that the ACLU has declared that prisoners "generally have the right to receive books, magazines and newspapers" under proper guidelines, what specifics did PEN's report discover about prison censorship?

What did the report find?

As the ACLU notes, prison libraries have always been closely monitored, and prison authorities "can generally decide to censor a publication for reasonable goals related to prison safety or security." PEN's report also acknowledges this, noting that courts have consistently allowed censorship in prisons "so long as the restrictions are reasonably related to the interests of incarceration."

However, the report found that censorship in prisons "has been applied at a scope and scale that far exceeds the denial of literature that even arguably could be used to escape from prison or enact violence." These prisons may ban books "based on the alleged threat of their content — a tactic similar to that of book banners that have targeted public schools and libraries in the past two years."

According to PEN, Florida has banned the most books from prisons among 28 states that record this data. The Sunshine State has purged 22,285 titles, while Texas came in second with 10,265 and Kansas in third with 7,699. Even New York — a state not typically associated with book censorship — was high on the list with 5,356 titles.

Many of these books are titles that could be seen as incitement of violence. PEN noted that in Michigan, for example, two banned books are "The Day of the Jackal," a fiction novel about a plot to assassinate French President Charles de Gaulle in the 1960s, and the thriller "Cuba Libre," set in the backdrop of the Spanish-American War.

"Prison Ramen: Recipes and Stories from Behind Bars," a cookbook that "offers ramen recipes that people can make in their cells," is banned in 19 state prison systems, PEN noted, because it makes references to razor blades and prison hooch. One art manual, "Anyone Can Draw: Create Sensational Artwork in Easy Steps," is banned in Florida because it depicts sexually explicit nudity, according to PEN's findings. Comedian Amy Schumer's memoir was similarly banned in Florida because it was "a threat to the security, order, or rehabilitative objectives of the correctional system" due to its sexual content, PEN reported.

Additional reasons that books have been banned, PEN found, include the book's physical appearance and cover, or whether the prisoner got permission to receive it. One book banned in Michigan, "Spanish at a Glance," is not allowed simply because it could teach prisoners "a language that staff at the facility does not understand."

What's next for prison censorship?

While there are genuine concerns when dealing with prison libraries, "the common concept underpinning the censorship we’re seeing is that certain ideas and information are a threat," the PEN report's lead author, Moira Marquis, told The Associated Press.

There are some prisons working to straddle the line between censorship and safety. The Michigan Department of Corrections told the AP it has created a literary committee "to review items that were previously placed on the restricted publication list, to determine if they should remain or be removed.” There are also a number of programs designed to raise the alarm on prison censorship, but they "are largely run by volunteers and struggle to keep up with the demand for books even absent censorship," the PEN report said.

Amidst the continued debate over book bans, PEN's analysis "is likely an underestimation due to the poor tracking of the information by states," The Hill reported.