‘Not my kid.’ How $7 pills get Charlotte teens hooked on fentanyl

The last bathroom stall on the left. An afternoon math class. The house across the street. This weekend’s party.

Fentanyl is easy for teens to get — and, these days, it’s even harder to escape.

After losing his best friend to the very drugs the two of them would use together, one Charlotte teen shared his winding journey from an innocent swig of liquor to a dependency on $7 pills, posing as Percocets, that circulated through his school.

“I didn’t know who I was,” said 17-year-old Dylan Krebs, remembering the height of his addiction. “I had completely forgotten everything about me.”

Not only could he not help himself then, he says, but his parents and teachers seemed to have no idea. He says students sold illegal painkillers in classrooms and recalls only once a teacher at school warning teens of the dangers of drugs.

“Everything is laced,” officials have long warned, and one fentanyl pill — about 2 milligrams — with the potent opioid is enough to kill a person.

During the 2022-2023 school year, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools logged at least 700 drug incidents. The data doesn’t specify drug type, but statistics and interviews reveal opioids and other controlled substances seeped not only into Charlotte’s high schools, but also its elementary and middle schools.

And that rising number only accounts for what administrators intercepted.

The Charlotte Observer previously reported that opioid addictions — which students and parents say at least partially developed in schools — landed several local teens in rehab over the summer. One July night, one fentanyl-laced pill, pressed to imitate a Percocet, killed a Hough High School junior.

In North Carolina alone, fentanyl has this year killed more than 2,000 people. Some were poisoned after reaching for a seemingly safe party drug, and some overdosed — knowing they’d been dealt a counterfeit pill and a chance at death.

Advocates and families left in the rubble of the drug’s destruction say intervention must start sooner.

Police say kids are now exposed to drugs earlier than ever, and cartels drained any possibility of safe experimentation when they started funneling the cheap, powdery drug into the United States. Authorities and health experts all say awareness, education and prevention need to catch up — and fast.

In this project, interviews held by the Observer unveil fragments of teens’ reality today: how they first learn about harder drugs, why they reach for them in the first place, and how they stay tapped into a steady stream — even as police dismantle tens of dealers at a time.

A ‘zombie’

Six months ago, Dylan Krebs needed fentanyl to get through the day. He wasn’t a person, the 17-year-old said. He was a “zombie.”

“I had no personality,” Krebs recalls. “I lost all sense of self... .“

He liked it that way, he said. The numbness fentanyl is clinically designed to provide had curbed his anxiety and depression. It was an escape he’d been looking for since fourth grade.

At 11, Krebs snuck his first swig of parents’ alcohol. He’d had signs of depression for two years at that point, he said.

As a seventh grader, he took his first puff of weed. Then he tried Xanax. Then, inhalants.

By the time Krebs walked through Hough High’s front doors as a freshman, he’d cooled off the drugs, he said. But during sophomore year, house parties raged, and he was setting new personal drinking records every weekend.

Halfway through the school year, Krebs found himself “completely freaking out.” He knew nothing about his future. He couldn’t summit the mountain of schoolwork.

“Can I really be happy?” he asked himself. “Or do I just want to feel nothing at all?”

Enter fentanyl. The synthetic opioid — used by doctors to treat cancer pain — is 50 to 100 times more potent than heroin or morphine. It’s a guaranteed escape from feeling.

Someone brought cocaine and fentanyl, disguised as fake Percocet, to a party Krebs attended around January, as a sophomore.

He’d had cocaine before and found it less powerful and less addictive — but the pressed pill’s lure was irrepressible. He started taking it monthly, then weekly, and, eventually, throughout the day.

First, the $7 pills were prescription Percocets, his dealers said. Then they had a “little bit” of fentanyl in them. Pressed pills are counterfeit, illicit drugs made to look like legal pharmaceuticals.

When Krebs found out he was buying 100% fentanyl pills, he didn’t care.

“I couldn’t go an hour without fentanyl without feeling super sick ... that was definitely a big motivation to just, like, keep doing it,” Krebs said. “I didn’t want to feel like s---.”

Krebs would take pills in his school’s bathrooms and classrooms, at home in his parents’ car — anywhere.

In May, he overdosed in a parking lot in Denver, about a 30-minute drive from his home and school, his parents said.

His parents rushed to meet him at a hospital in Huntersville. His friends sat by their phones. They all waited for an update.

Krebs would be O.K., a doctor said, but tests showed he had fentanyl in his system.

He told Krebs, who was fading back into consciousness, that a dose of fentanyl the size of the tip of a pen was enough to kill him.

“Oh god,” Krebs said. “Never again.”

“Never” lasted about four days, his father said.

His parents got him into outpatient rehab in late May. Krebs still used daily.

But when Cornelius Police Department officers arrested his dealers on June 14, he was forced into sobriety for the first time in six years. He’s been clean since.

He actually liked it. He remembered what kind of music he liked and made friends who wanted to know more than just his preferred drug.

“Rehab is dope as f—,” he sent in a group text his parents found later when checking his phone.

“It’s the best thing that’s happened to me.”

They responded:

“That’s really awesome.”

“So happy for you.”

“I wish I could get there.”

Laird Ramirez, the 17-year-old who died after taking a fentanyl-laced pill in July, was in that chat. He was one of Krebs’ best friends.

“He wasn’t just another person I got high with,” Krebs said. “He was real. He was a close, amazing friend.”

The night before Ramirez died, he called Krebs for advice. He thought one of of their friends was overdosing after taking too much fentanyl.

Krebs, who had now been sober for two weeks, told him to call 911 and check the friend’s pulse. He also told Ramirez to never touch the drug again.

Ramirez never called for an ambulance, and the friend brushed past death, Krebs said.

But the next day Ramirez was found dead in a friend’s home in Cornelius. He’d been unconscious for 12 hours, paramedics told his parents.

The toxicology report would show he had a three times the lethal dosage of fentanyl in his system, his mother said. She later found the other half of the pill in his wallet.

Ramirez’ parents, Gwyneth Brown and Chris Ramirez, were sure their son hadn’t used drugs before July 1 — and they believed he didn’t know the pill he took that night was laced.

But Krebs’ father, when checking his son’s phone, once saw a message from Ramirez.

“I want to take this Perc so bad,” it read. “But I can’t because my nose is so stuffed.”

Interviews with Krebs and Hayden Garvey-Knapp, Ramirez’s 16-year-old girlfriend and fellow Hough High student, reveal what his parents would soon learn: he knew what he was taking.

He accurately called those pills “fenty percs,” Garvey-Knapp said.

His parents now know their 17-year-old wasn’t a first-time user. Since his death, they’ve dedicated themselves to activism and education about the deadly drug circulating through Charlotte and across the country.

‘...Promise you won’t judge?’

“Can I tell you something and you promise you won’t judge?” Ramirez asked Garvey-Knapp, his girlfriend, over Snapchat one night.

He was responding to her previous message: “What the hell? Why would you do that?”

He’d just told her he snorted his ADHD medicine that night, but that wasn’t all.

After a knee surgery, the hydrocodone prescribed by doctors pushed him to Percocets, he told her.

But Brown found that bottle of hydrocodone in her son’s room after he died. It was full, she said, just like his ADHD prescription.

”He couldn’t possibly be an addict,” she thought. He hadn’t even gone through the drugs stowed in his own room.

But he was reaching for other things, he told Garvey-Knapp. He’d tried cocaine, he said, and sometimes he’d crush down and snort Benadryl.

If he took enough, he said, it mimicked the effects of LSD and mushrooms — things not readily available to him.

But the pressed, fentanyl-laced Percocets he’d soon become addicted to were well within reach.

Garvey-Knapp didn’t sleep that night. She worried he would overdose at any moment, and she thought about calling an addiction center.

Her reaction was enough, he said the next morning. He’d quit immediately.

And he did — for about a month, friends later told Garvey-Knapp.

“It was a coping mechanism, for sure,” she said. Friends told her he would have one anytime he got too sad.

Krebs understood; he did the same.

“I don’t think I’ve ever heard of a fentanyl addict without mental issues,” he said.

His father, Brendan Krebs, says addressing underlying mental health issues is a first step for parents and educators.

Treating them like criminals, calling now-dead kids “druggies,” and threatening arrests won’t help them, he says.

But the Krebs family has found a place that does help.

This summer, they moved to Pineville from Cornelius, away from Hough High so that Krebs is closer to his new school: Emerald, the only recovery high school in the area.

“They treat Dylan as a student and as a person before they treat him as a number,” Brendan Krebs said. “They look for his mental health and his well being before they look for test scores.”

Now, for the first time in six years, Brendan Krebs has his son back. Krebs leads meetings at rehab. He tells his parents about his day. He remembers the kind of music he likes.

“There’s still a lot of work that we have to do,” he said. “But without Emerald, there’s no way he would have survived.”

The Emerald School of Excellence can’t act as the only rehab students get, said founder and president Mary Ferreri, but it’s a huge addition of support.

The school’s focus may be more needed than ever, data suggests.

Drug incidents in schools reported by CMS leaders have gone up 38% in the last 10 years, data shows, while enrollment has remained flat or fallen most years. That’s compared to a 10% statewide increase reported by all North Carolina public schools over a 10-year period ending in 2022, the most recent data available.

According to the CMS Code of Conduct, schools are required to refer any student found with drugs to the Student Assistance Program. They can also enlist those who may be showing signs of drug use, even if they’ve not been found with drugs.

The Observer requested data on SAP referrals, but CMS does not track them, according to Susan Vernon-Devlin, CMS’ executive communications director.

For confirmed crimes — like possession of drugs at school — districts are required under state law to compile the data and send it annually to state education officials.

Fentanyl in schools, used by teens

Statewide, district-level data show possession of drugs at schools is the most common reported offense among students and has been for at least a decade. And the amount of drugs found with students in school has increased across North Carolina, data show.

Raynard Washington, director of Mecklenburg County Public Health Department, says the population of 18 to 24 year olds are particularly at risk nationally. Schools are an important place for intervention and education, he said.

The Biden administration last week sent a letter formally alerting schools that kids and teens have easy access to illegal pain pills. The letter — in bolded and underlined font — says schools need to have naloxone on hand and train students and employees on how and when to use it.

“Our drug supply has gotten more dangerous,” Washington said. “It is challenging... and more likely that kids are gonna run into something that is (going to be fatal).”

The health department has bought enough naloxone to stock the overdose-reversal medication in every Charlotte-Mecklenburg School, Washington said. Both students and adults — teachers, visitors and parents — could potentially need the life-saving treatment in a school building.

The health department also supplies Narcan to local police, Medic and other agencies that need the resource to “leave behind” when called to an overdose emergency involving someone who is likely to overdose again.

Fentanyl is commonly found in drugs that pose relatively less immediate health risks, such as marijuana edibles and cocaine or ecstasy. Those using fentanyl in their early adulthood likely began buying illegal drugs or being prescribed legal opioids during teen years, he said.

Nationwide, for years, communities have recognized fentanyl and associated drug use among teens as a rising crisis — part of the broader opioid epidemic, Washington says.

“The curve in Charlotte sometimes lags behind other big cities ... We are in the thick of it.”

The public health emergency has long warranted a response, Mecklenburg County Commissioner Mark Jerrell wrote in a statement read at a recent news conference held by the sheriff’s office.

“It is essential to address the societal factors that contribute to this issue, to include reducing the stigma surrounding substance use disorders, providing access to mental health services and addressing socioeconomic inequalities that often drive individuals toward drug misuse,” he said.

At that same event, Kenny Robinson, the founder of Freedom Fighting Missionaries, spoke about fentanyl’s impact beyond schools and into the community he is most tapped into.

“We are already losing 70 to 75 black youth to gun violence [each year],” he said. “When you add 70 to 75 drug overdoses to that, that is entirely too much for one community to bear.”

Fentanyl has killed 137 people so far this year, said Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department’s Chief of Police Johnny Jennings.

“Imagine if we had 137 homicides in not even a year,” he said, adding that he thought community response would be more forceful if the statistic weren’t drugs.

Everyone is fighting the same war, said Greg Jackson, the founder and executive director of Heal Charlotte, an organization focused on neighborhood revitalization.

“Fentanyl has been a problem in our community, and everybody’s community,” he said, “No matter your color, but definitely... in the Black community.

“We want to highlight that unapologetically, and with a lot of aggressiveness, assertiveness and force. It needs to be addressed. It needs to be a public health issue, a public health crisis.”

Teens dying from overdose

Drugs are not meant to be part of anyone’s legacy, Jackson said. He’s prepared to force that message inside schools, he said, by any means necessary.

“It’s not necessarily part of the curriculum of CMS, to have this conversation,” he said. “But we’re all pressing for that right now.”

Debbie Dalton, a local mother who lost her son to fentanyl poisoning, is all too familiar with the legacy-ending drug.

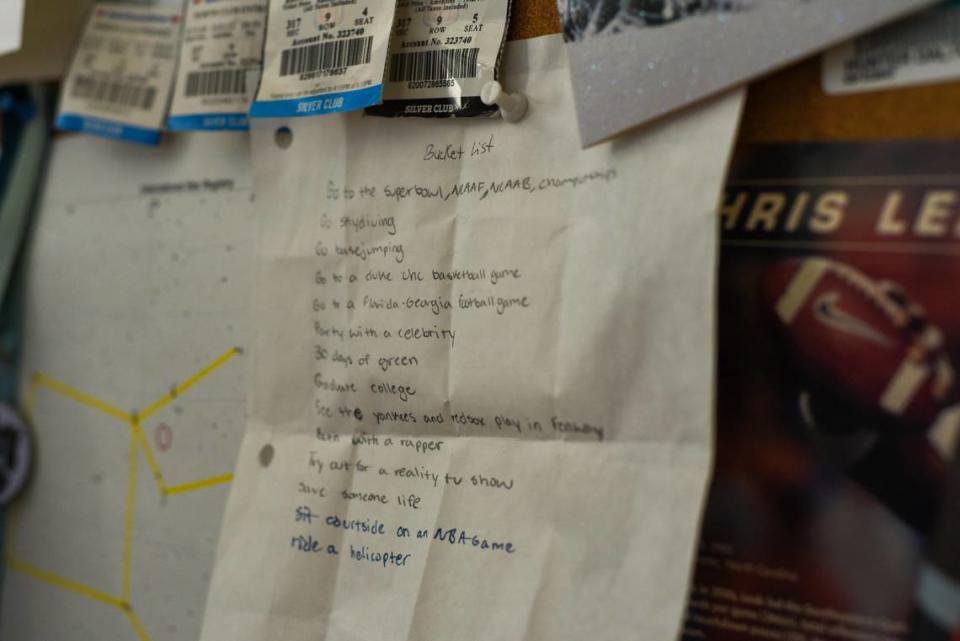

Her son, Hunter Dalton, died after he took a line of fentanyl-laced cocaine in 2016. The 23-year-old had grown up on Lake Norman, where he attended Hopewell High School, and had just graduated college. He was hospitalized for seven days, and he never regained consciousness.

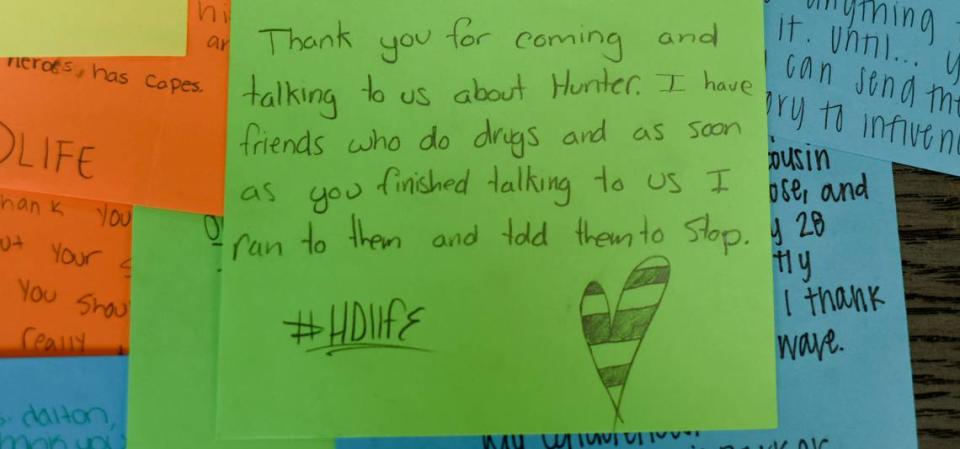

Dalton’s presentations provide some of the only education students now get in CMS — and that’s only if schools let her in.

The Hunter Dalton #HDLife Foundation — a nod to Hunter’s relentlessly positive outlook on life — routinely sat her next to Attorney General Josh Stein, she said. They talked about how to mandate fentanyl-specific curriculum across the state, and they looped in Gov. Roy Cooper on conversations about what police need to thwart the drug’s traffic.

When the pandemic derailed their momentum, she refocused on what she can do locally.

With little direction from the state and district, schools have a duty to be truthful with kids, she said. Drugs aren’t just bad, they’re now uniquely lethal.

CMS previously told the Observer it makes curriculum decisions based on data — and schools don’t see a high enough number of pill or fentanyl-related violations to expand overdose education across the district. A school counselor said most violations relate to alcohol or marijuana.

While no Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools board member would agree to be interviewed by the Observer, previously the district said it did not plan on altering its current drug education, which is currently mandated under North Carolina Health Education standards. Any future curriculum changes would likely incorporate the DEA’s “One Pill Can Kill” campaign, a spokesperson said, which focuses on laced or counterfeit drugs

The reality is that some kids start thinking about drugs in elementary school, Dalton said. In middle school, there’s a chance of interception before they reach for alcohol, vapes or weed.

By high school, there’s no room for “cop outs,” she said.

Ramirez’s mother can’t help but be frustrated with teens’ brazen drug use.

“They’re dumb,” she said. “They’re dumb because they’re not educated, and they’re not educated because CMS is turning a blind eye to the fentanyl problem.

“They’re just utterly in denial.”

There’s no room for shunned eyes or “not my kid” mentalities, both Dalton and Brendan Krebs said.

“Just because your kid is on a sports team, doesn’t mean that they’re not using,” Krebs said. “And just because your kid looks like a kid from a punk band doesn’t mean that he is using.

“We don’t know what a user looks like anymore.”