Not all soldiers return from war. These are some of their stories

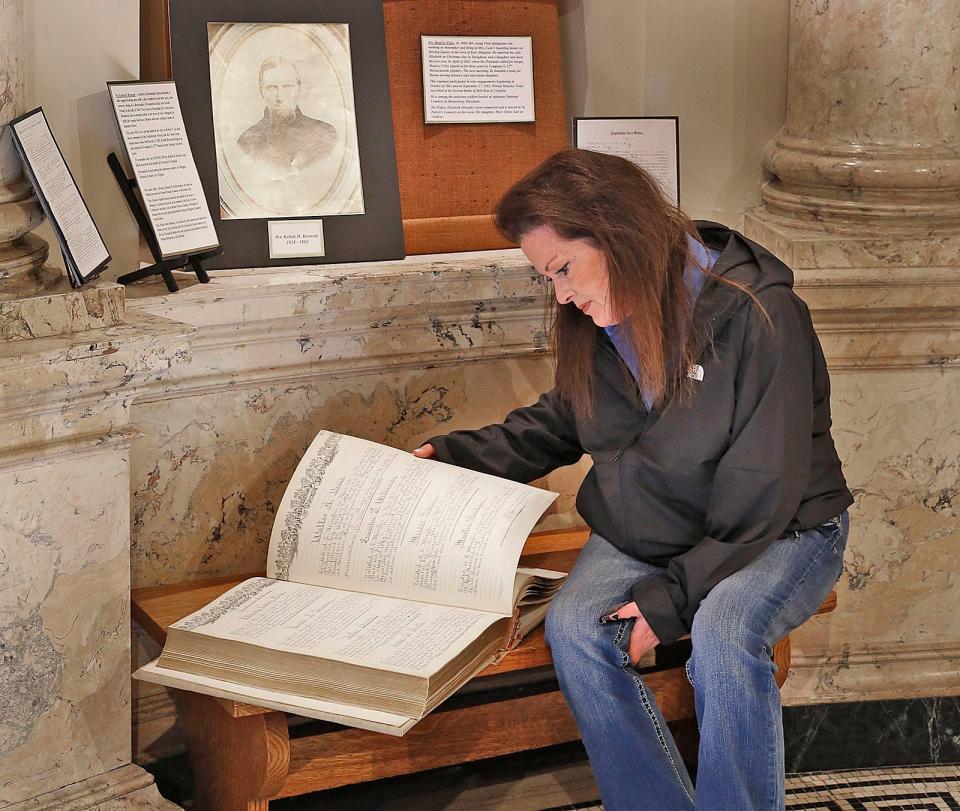

ROCKLAND − These memorable faces with their haunting, direct gazes might have been lost to history. But then Pamela Ryan found a book about them in a closet at the Grand Army of the Republic Hall. She was ecstatic.

And now, several years later, they are part of an exhibit, "Faces of the Unreturned," honoring 14 of the 25 Civil War veterans from East Abington (now Rockland) who never came home from the war.

Fittingly, the exhibit is in the rotunda dedicated to the Civil War veterans at the Rockland Memorial Library.

You might consider the town's longest-serving veteran, Capt. Lewis Reed, a lucky man. In July 1861, he enlisted in the new 12th Massachusetts Infantry and won promotions over his four years and four months of service. He returned home and lived to age 83, dying in 1925.

Pvt. Elbridge G. Poole did not fare so well. At age 19, answering the call for soldiers after Fort Sumter was attacked in 1861, he enlisted in the Massachusetts Infantry, "unaware of what was to come," as Ryan writes in a brief summary.

Nearly a year-and-a-half later, in 1862, he was wounded at Antietam, one of the deadliest battles in American history. His leg was amputated in a field hospital. He died 28 days later, likely in agony, and was buried at Antietam National Cemetery in Sharpsburg, Maryland. Poole was 21.

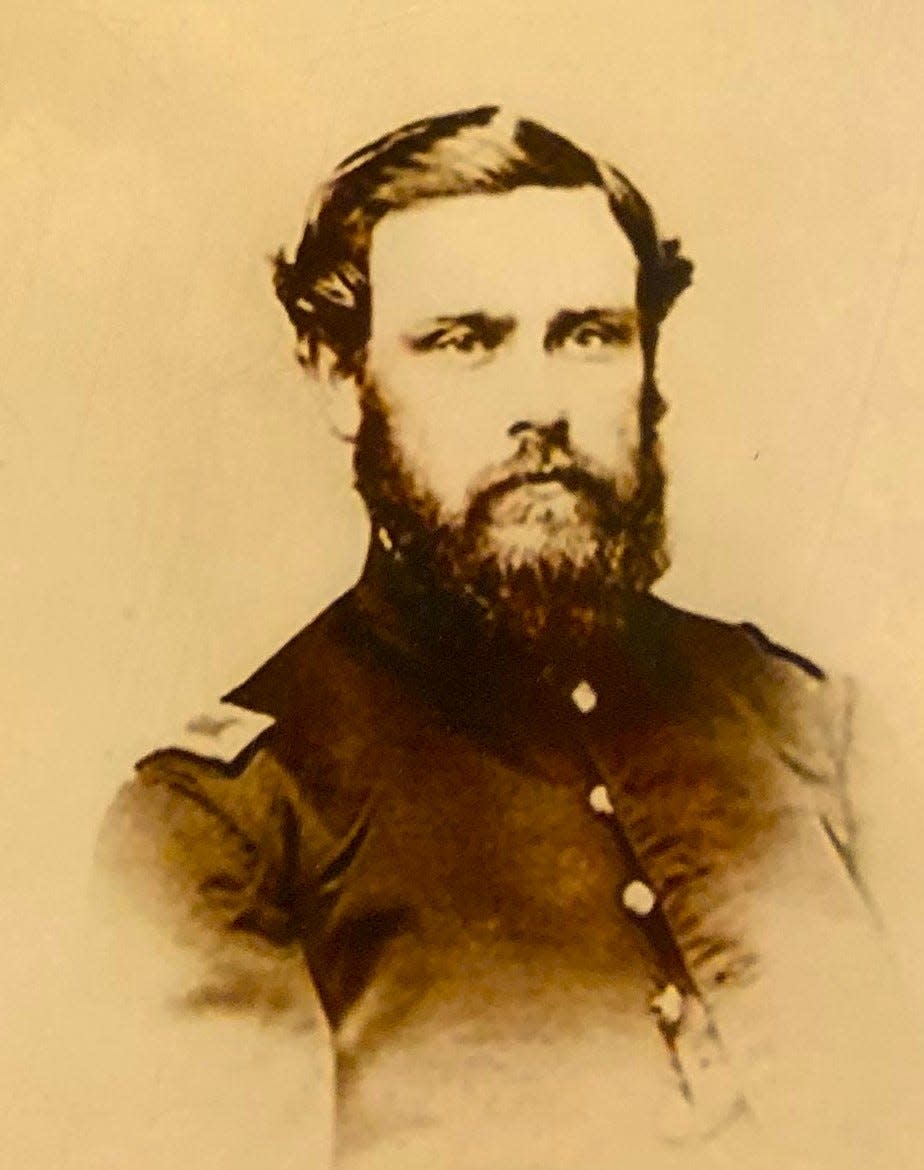

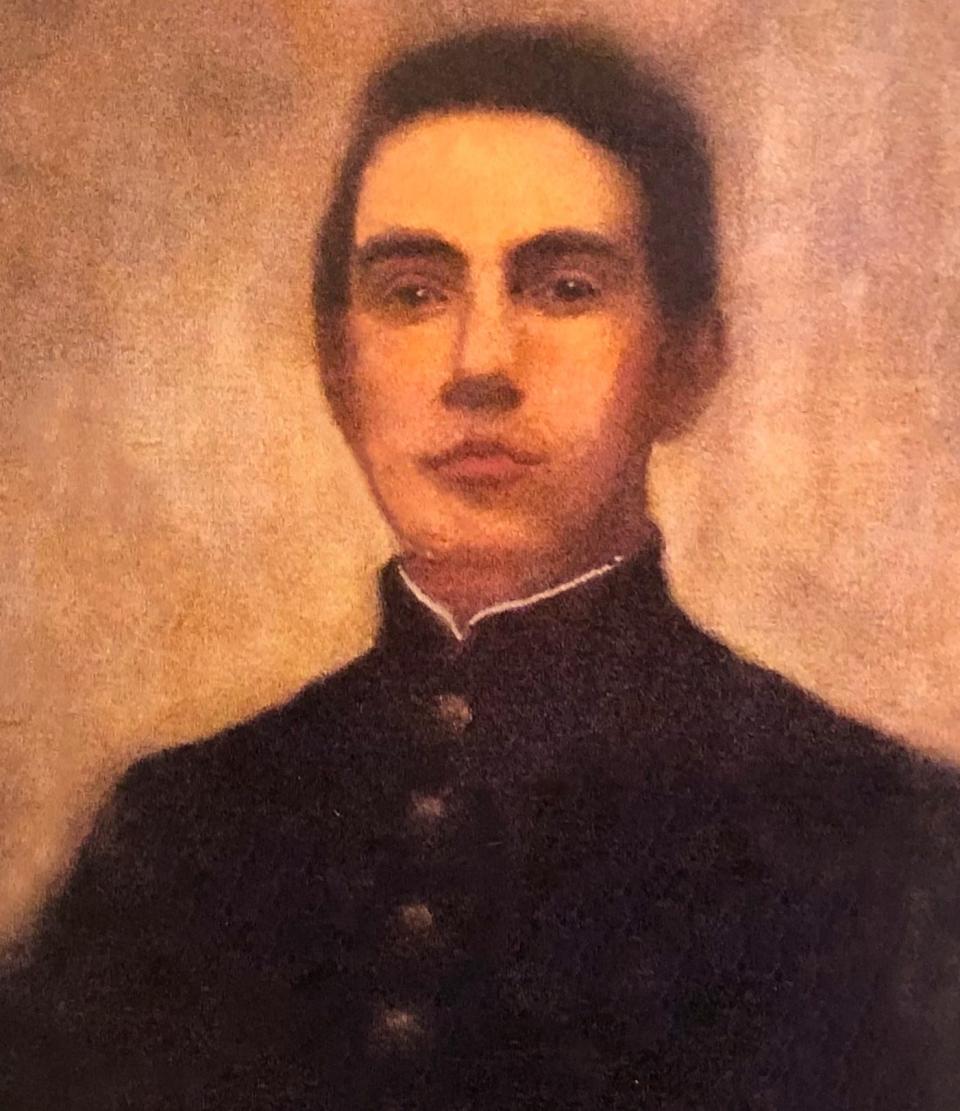

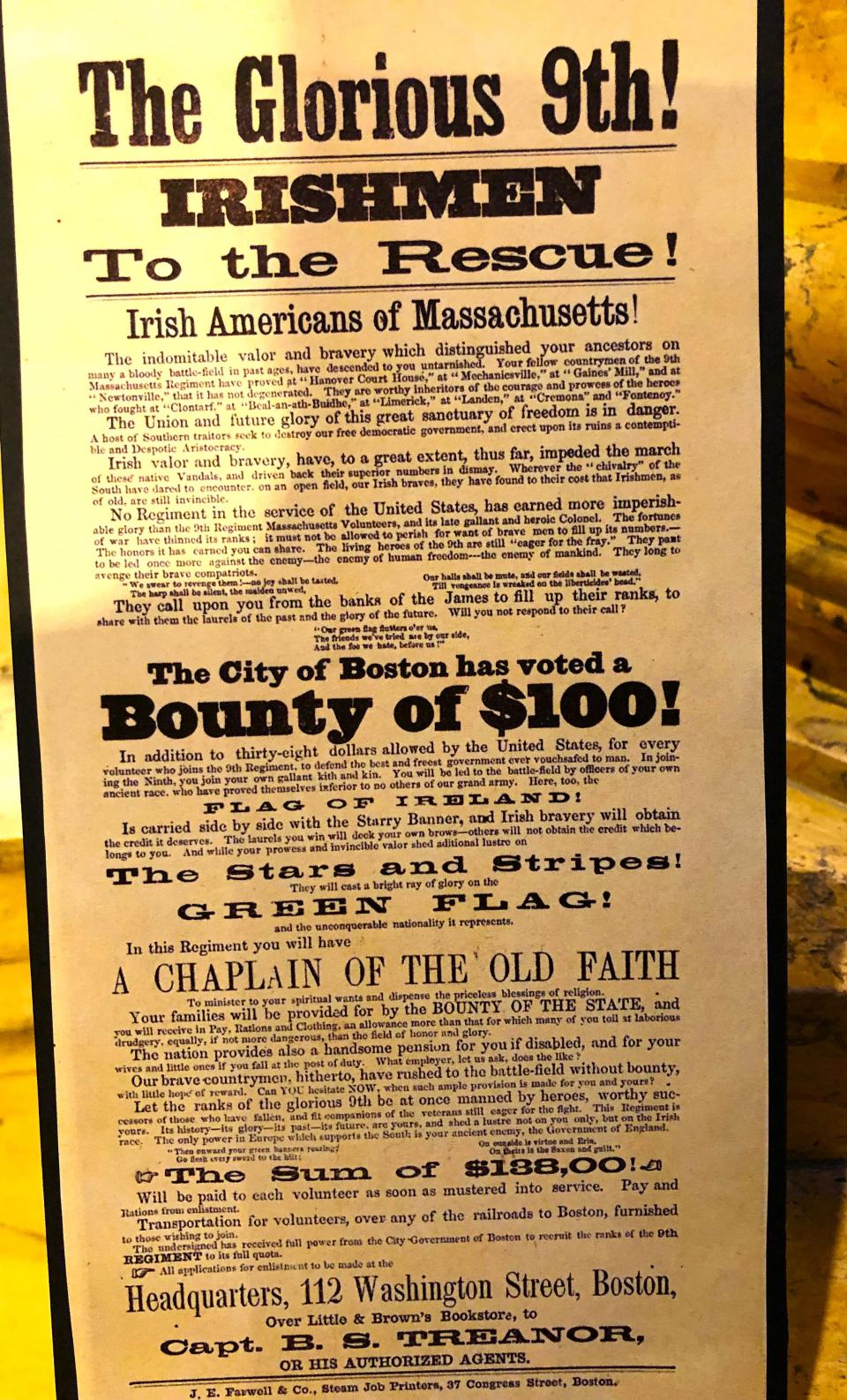

Looking at the faces of the soldiers in the library exhibit, one is struck by how young some were, how many were Irish immigrants and how strong both the call and the urge were to serve.

"If they served, they would be granted citizenship," Ryan said. "They already owned houses, they were invested in the town. This was home for them." Some of their houses are still standing today.

Mary Maher, of Rockland, who is a nurse, stopped by to see the exhibit and was interested in all of the short biographies and what she learned about both past and present.

"I realized that most of those who died wouldn't have done so today, given the advances in medicine with antibiotics, aseptic techniques and surgical procedures," Maher said. "Such a waste!"

She was surprised to learn how during the Civil War "one could 'buy' one's way out of conscription by paying a certain amount of money to someone to take your place. Of course, it was the wealthy who could afford this option and the poor who were tempted to take the deal."

Reading the notes about the descendants of the veterans, she said, "I was also struck by how so many of these soldiers' families still live locally. I guess I was surprised by that, given what a mobile society we are now."

Ryan, a Rockland resident with deep roots in the town, has long been intrigued by the stories of the town's Civil War veterans.

Over the past six years, she has done extensive research, both online and in the library. She has contacted veterans' descendants she found online and organized the exhibit, which remains in the library rotunda for another two weeks.

"Faces of the Unreturned," which opened in November, was made possible by the Friends of the Rockland Memorial Library, in collaboration with the Rockland Historical Commission and the Hartsuff Memorial Association at Rockland Grand Army of the Republic Hall.

In her research, Ryan found that Rockland, once known as East Abington, had 25 men out of hundreds who went off to fight who never returned home alive. Some were missing in action; others were buried in battleground cemeteries; the bodies of a few came back.

The names of the 25 men are inscribed on a marble tablet, "Our Unreturned," placed in the rotunda, high up under the cupola, at the rotunda's dedication in 1905.

They never returned. She makes sure they are not forgotten

Over the past several years, Ryan, a member of the town's historical commission and the Hartsuff Memorial Association, has done extensive research in the town library archives about the veterans.

She has also digitalized the town's collection of all its Civil War veterans.

"I love Rockland history," she said.

Several years ago, she was at one of the library's Art in the Rotunda displays with works by local artists. She happened to look up and see the Civil War tablet with the names of those who never returned above her. She recognized the names of some of the soldiers.

It struck her that while people in the library were aware of the exhibit, no one seemed aware of the original purpose of the rotunda: remembering the Civil War veterans.

"I made a point of watching and saw no one was looking up (at the tablet)," she said.

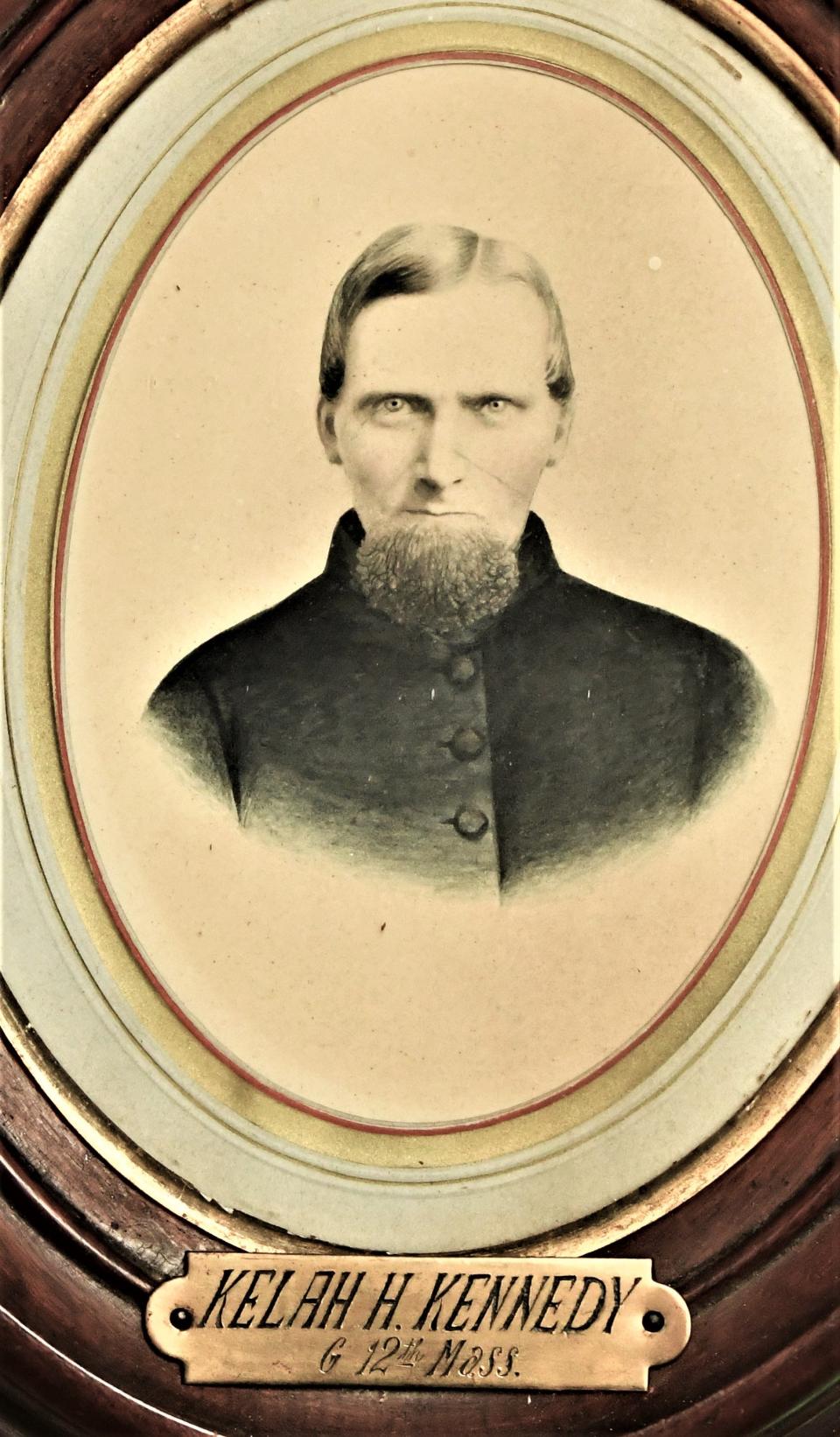

Once she found the War Sketches Book in a closet at the GAR Hall, she knew she could put together brief stories. After that, she saw portraits and the photos of the veterans at the GAR hall. She photographed them all. She thought about how those images of the veterans who never came home might be the only evidence or proof "that they walked the earth, maybe the only photo that was ever taken of them."

"It was a game changer," she said. Ryan realized she could match the faces with the names of the unreturned. She also found out what became of some of their wives and children. For example, Mary Beals (Lovell) Smith, widow of Lt. James G. Smith, did not remarry and lived to age 91.

One of the photographs Ryan found shows a public notice from Sept. 8, 1862, headlined "We Are Coming Father Abraham," a reference to President Lincoln.

The notice calls on all men to go to a meeting in an old church in East Abington that night "for the purpose of raising the full quota of the town without a draft."

After a number of men signed up, Ryan said, "the whole town walked them to the depot with a band playing" as they went off to military training.

She has contacted as many direct descendants − great-great-great grandchildren − as she could find online. When the library held a reception for the exhibit's opening, the first person to arrive was the great-great-great grandson of one of the unreturned, Keilah Kennedy.

"It's all about them," she said. "I feel lucky that I get to tell some of their stories. If you talk about people and that means they are not forgotten, it is an honor."

This article originally appeared on The Patriot Ledger: Rockland resident creates Civil War exhibit 'Faces of the Unreturned'