‘We’re not taught to speak out’: Asian Americans find their voice amid rise in hate

Natty Jumreornvong was outside Mount Sinai hospital on the Upper East Side of New York around 11am one morning in February when a man approached her.

Related: 'Our community is bleeding': Asian American lawmakers say violence has reached 'crisis point'

“Chinese virus,” he spat out. She told him she was a medical student and tried to walk away, but he followed her, kicked her knee and dragged her across the ground. She called out for help, but nobody came to her assistance.

The incident was just the latest and most severe case of anti-Asian hate Jumreornvong has seen over the last year. Last April, a woman with a child spat on her and called her racial slurs. Patients have called her “Kung Flu”, and she’s seen Asian patients with bruises who say someone came and hit them but would not say who, potentially out of shame.

“It’s been going on for a while,” said Jumreornvong, who grew up in Thailand and came to the US for college.

Since the attack in February, Jumreornvong has made a point of speaking out against anti-Asian hate. She wrote an op-ed about her experience, rallied other students to push their medical school to critically look at Asian discrimination and spoke at a rally of New York City healthcare workers against anti-Asian hate.

It’s still all new to me, activism, and I think that’s what a lot of Asian Americans are starting to feel too

Natty Jumreornvong

Such vocal activism is new to Jumreornvong. She recalls “shaking like a leaf” when she was speaking at the healthcare workers rally, and she has received hateful messages online from people for talking publicly about her experiences.

“It’s still all new to me, activism, and I think that’s what a lot of Asian Americans are starting to feel too,” Jumreornvong said. “We’re not really taught to speak out.”

But Jumreornvong said many people have reached out to her saying that her experience resonated with them. “Sharing stories can be really powerful, or else people don’t think [the hate] exists,” she said.

Jumreornvong is a part of what has become a massive movement to stop anti-Asian violence in the US as the number of hate-related incidents reached an alarming high over the course of the pandemic. Stop AAPI Hate, a not-for-profit coalition that has been tracking anti-Asian incidents since the beginning of the pandemic, has reported at least 3,800 incidents ranging from being spat on to verbal and physical assault.

While hate-related incidents have been taking place throughout the course of the pandemic, two high-profile, violent incidents in January against elderly Asian men, one of whom died from his injuries, gave momentum to the issue. After the murder of six Asian American women in a mass shooting in Atlanta, many Asian Americans say that the fear of being attacked has hit a breaking point.

The last few weeks have seen dozens of rallies against anti-Asian hate across the country, viral social media campaigns spreading awareness of the issue and over $25m in donations to groups supporting Asian American and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) causes.

For many historians and advocates, this mobilization feels like the first time in decades when Asian American activism has been seen at such a widespread scale. The rise in hate-related incidents and crimes, along with the racial reckoning provoked by the police killing of George Floyd and the ensuing Black Lives Matter protests, has caused a broad coalition to form within a diverse racial group.

Asian Americans make up 20 million of the US population and have backgrounds in more than 20 countries in Asia, each with distinct languages, cultures and history. No single ethnic origin dominates the group, and about 60% of Asian Americans were born in another country, according to the Pew Research Center.

Despite their vast ethnic, generational and cultural differences, Asian Americans have found common ground over the discrimination.

“In this moment, you see Asian Americans coming together because we all recognize that shared pain and that shared sense of being othered,” said John Yang, president and executive director of the advocacy group Asian Americans Advancing Justice. “We understand what it’s like to be labeled as a foreigner, regardless of whether we were born in this country.”

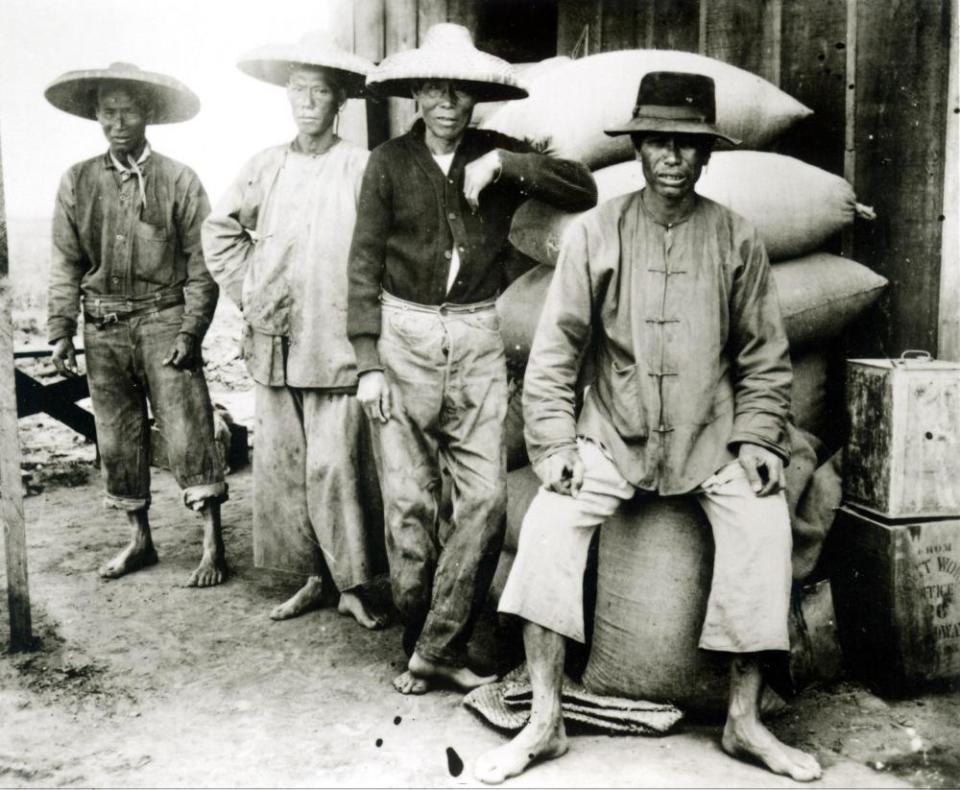

This experience of racism and xenophobia is something that Asians in America have shared since the 1800s, when immigrants from Asia started coming to the US. The racist “yellow peril” phenomenon is used to describe the fear Americans had concerning Asian immigrants, who were believed to be dirty and ridden with diseases, and their potential stain on the western world. No matter whether a person was Chinese, Japanese, Korean or Filipino, they were regarded as “yellow peril”.

“They were different, but they were merged together” in the US, said Linda Trinh Vo, a professor of Asian American studies at the University of California at Irvine. The phenomenon worked “to prevent them from being integrated into this country”.

Up until the late 1960s, people of Asian descent identified themselves by their ethnicity and were broadly referred to as “Oriental”, “Asiatic” or “Mongolian”, Vo said, with some frequently called racial slurs.

But in 1968, a group of graduate students at the University of California at Berkeley, inspired by the Black Power Movement, wanted to band together to join the broader fight for racial equality.

Looking to emphasize that they were American even as people of Asian descent, they chose to name their political alliance under a new umbrella term for themselves: Asian American. This creation of the Asian American Political Alliance in 1968 was the first time the term Asian American was documented.

By creating the term Asian American, the students marked a desire for multi-ethnic, self-identified unity that would emphasize their belonging in a country that, for nearly a hundred years, has always treated them as foreigners.

“Uniting under the banner of Asian American was really a recognition in which the US system of racial domination lumped together people of many different Asian ancestries in the US and treated them alike, even though we have profound differences,” said Daryl Maeda, professor of ethnic studies at University of Colorado Boulder.

The kinds of conversations we’re having now were unthinkable even two years ago

Manjusha Kulkarni

Many Asian Americans are more likely to align themselves with their ethnic identity, and the shared language and culture that comes with it, over the broader Asian American identity, Maeda noted. Thus, “it’s a political commitment to embrace the term Asian American,” he said.

Activists say they have been encouraged by the number of Asian Americans who have not only started to become vocal about their experiences with hate-related incidents, but also are starting to grapple with broader conversations about how race plays a role in their lives.

“The kinds of conversations we’re having now were unthinkable even two years ago … getting at questions of being perpetual foreigners, being told you speak English well,” said Manjusha Kulkarni, executive director of the Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council and a co-founder of Stop AAPI Hate. Asian Americans have been talking about the experience of changing their names to ones that are more palatable to Americans and being hypersexualized as women.

“It’s critical for us to understand and vocalize our experience, to say it’s not OK to be treated as a foreigner when we’re just like everybody else,” Kalkurni said.

Lily Li, who grew up in New York and now works in the city as a social strategy and content coordinator, was encouraged by the turnout at a recent Black and Asian solidarity march in New York.

“I was so proud to be there just walking through the streets. There were people from the older generation that were walking with canes, there were people from the younger generation who brought their kids. I saw kids as young as six years old marching with their signs,” Li said. “I felt like we were raising a generation that is becoming accustomed to seeing the Asian American community activated like this and walking amongst their allies.”

Racism preceded the pandemic and racism will continue after the pandemic ends

Manjusha Kulkarni

Attention around anti-Asian discrimination has also put a renewed focus on Asian-run businesses. Li is a volunteer with Send Chinatown Love, a not-for-profit supporting mom-and-pop Asian businesses throughout New York, including her parents’ restaurant in Queens. The organization has raised over $500,000 to help restaurants facilitate online ordering and recently installed hundreds of paper lanterns over Chinatown to attract people to the business district, which has been badly hit by the pandemic and anti-Asian sentiment.

In response to pressure to address the growing number of racist incidents against Asian Americans, the White House unrolled a series of measures, including $49.5m of funding dedicated to community programs that help victims of attacks, and called on the justice department to make new efforts to enforce hate crime laws and collect data.

Advocates praised Biden’s actions, but have emphasized that attention to the issue needs to continue and ultimately go below the surface to address the root causes of discrimination.

“Racism preceded the pandemic, [and] racism will continue after the pandemic ends,” Kulkarni said. “The pandemic is just the latest iteration of this racism, but it could have been something else that prompted it. The ‘something else’ will prompt it once again unless we’re able to take really decisive action against white supremacy.”