Notes and tones: Frank Kimbrough's musical and personal legacies live on

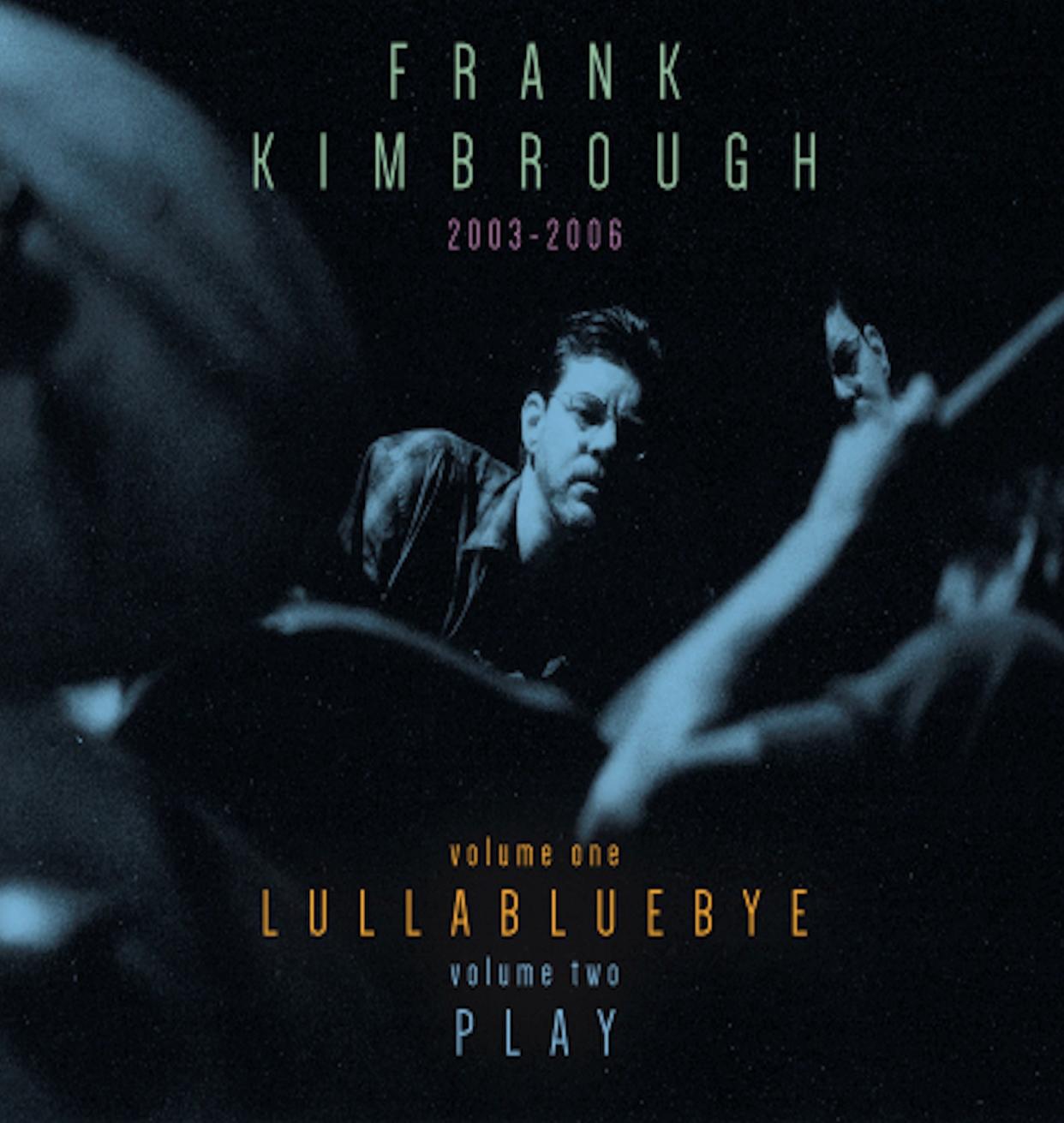

As I ready to submit this column for your reading pleasure, I’m listening to the late pianist Frank Kimbrough’s take on “You Only Live Twice,” which appears on his “Volume I: Lullabluebye” (Palmetto), a trio session with bassist Ben Allison and drummer Matt Wilson.

While the opening notes and intro to his “version” of “You Only Live Twice” are easily recognized from its namesake James Bond film, I had to double-check the CD credits just to be sure. I saw the inclusion as atypical repertoire for the quite imaginative and impeccably improvisational pianist.

Then again, historically speaking, many jazz musicians — perhaps Sonny Rollins is the best example — have mined everything from show tunes, musicals and Broadway hits to movie themes and the Great American Songbook, embracing such material with a sense of duty, responsibility and purpose. They both honor and respect the work’s origins on the one hand and make the rendering their own.

This is exactly what Kimbrough, Allison and Wilson do here. It also happens to be the sole non-Kimbrough original on this 10-selection disc, save “Ben’s Tune,” an Allison composition.

“Lullabluebye” is the first of a remixed and re-mastered, soon-to-be reissued two-CD Kimbrough set titled: “2003-2006.” Its companion, “Volume II: Play,” is also a trio date. Released three years after its predecessor, also as a 10-selection recording, it showcases the work of bassist Masa Kamaguchi and one of the pianist’s influencers, drummer Paul Motian, who joins Kimbrough on this musical excursion.

Not surprisingly, Volume II is comprised of all originals except for the title track, which Motian composed.

Though the two recordings are clear demonstrations of the classic piano-bass-drums trio configuration, each recording stands on its own. After listening to each multiple times, I came away with the feeling that Volume I explores more expansive, outgoing material whereas Volume II seems quieter; the pianist-led threesome spends more time looking and searching inward.

There are similarities between the two discs for sure. Kimbrough spent lots of time with Thelonious Monk’s music. In fact, his final release — in 2018 — is "Monk's Dreams: The Complete Compositions of Thelonious Sphere Monk" (Sunnyside); it’s nothing short of exhaustive and masterful as Kimbrough, working in quartet with multi-reed player Scott Robinson, bassist Rufus Reid and drummer Billy Drummond, recorded every known Monk composition, which filled six CDs.

Monk’s imprint can be heard at differing, intermittent points throughout both discs. The same can be said for the likes of Bill Evans, Keith Jarrett and Herbie Nichols who, like Monk, served as the catalyst for a Kimbrough “musical chapter” and multiple releases under the ensemble known as The Herbie Nichols Project.

I was fortunate to hear Kimbrough live on multiple occasions and in a variety of settings — from his trio to his tenure as the pianist for more than 25 years of the Maria Schneider Orchestra, which made its lone Columbia appearance in March 2008. He’s heard on virtually every Schneider release from 1996 through 2020.

We are lucky that Kimbrough was quite prolific and left the world a dozen or more recordings under his own name as well as contributing to perhaps 100 additional entries in support of his many colleagues’ endeavors.

Kimbrough died in December 2020, at 64. A native of North Carolina who took to piano as essentially an infant, he moved first to Washington D.C. in 1980, and New York a year later. Kimbrough’s passing had an enormous impact on many people.

Shortly after his death, the website AllAboutJazz.com ran a piece titled “Frank Kimbrough: From Now to Forever — A Remembrance.” In part, Brooklyn-based Ludovico Granvassu, editor-in-chief of the site’s Italian edition, offered a compressed biographical snapshot of Kimbrough.

Wisely, though, AAJ also decided to include wide-ranging, first-person comments from musicians. Here’s but a few condensed selections of musician remarks. The article and the entirety of the comments can be found online.

Palmetto Records founder Matt Balitsaris said, "Kimbrough was what a musician should aspire to be, but very few are. He played without ego, in service of whatever the music and the situation asked of him."

"Though he was insanely knowledgeable, his artistry was led by some kind of incredible trust in what each moment would bring to the music," longtime cohort Schneider said. "Over the years, I've heard him invent hundreds of intros from that magical place, on the fly, that were as sophisticated as any Debussy prelude."

Saxophonist Immanuel Wilkins was a student of Kimbrough at Juilliard, and said: "He was like an uncle to me and deeply cared for all of his students. He believed in me often in times where I felt like an outsider, and he was a wealth of knowledge. ... When I look back on our relationship, I think about the boundless support he gave me in all aspects of my life. I hope I continue to make him proud."

Drummer Wilson said that, "in addition to our strong musical bonds, we shared another interest, talking. Frank and I loved to visit and tell stories. We would get deep about music, teaching, life and then share an anecdote that would have us bursting into laughter. His stories flowed just like the beautiful music he offered us."

Jon W. Poses is executive director of the “We Always Swing” Jazz Series. Reach him at jazznbsbl@socket.net.

This article originally appeared on Columbia Daily Tribune: Notes and tones: Frank Kimbrough's musical and personal legacies live on