‘There was nothing to help me’: how the pandemic has worsened opioid addiction

Destiny Rozek, 22, of Holbrook, New York on Long Island has struggled with opioid addiction for the past four years, a struggle she said has worsened during America’s coronavirus pandemic.

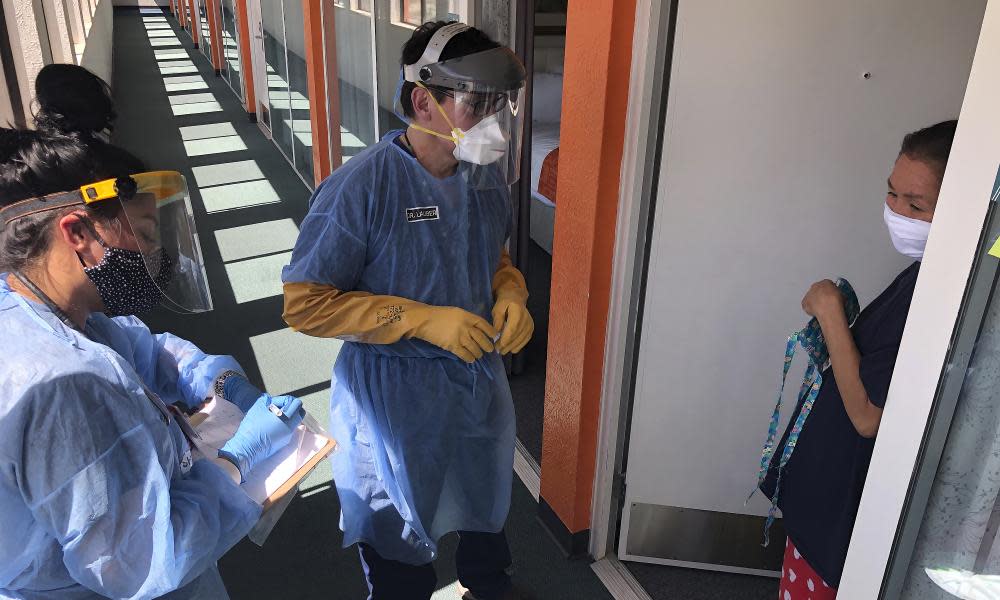

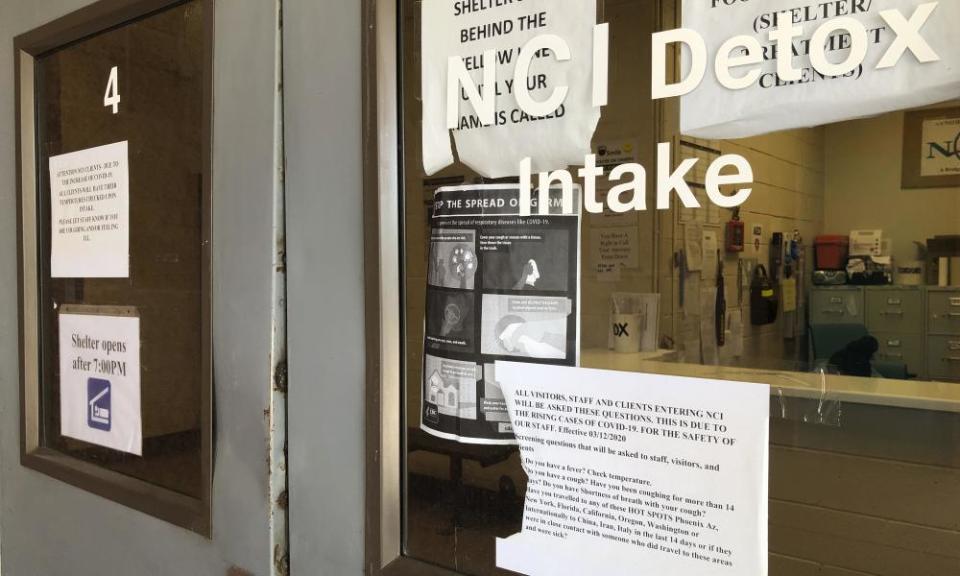

Rozek explained that several detox facilities have closed and coronavirus safety protocols have limited the assistance several other facilities once provided. She went to a detox facility several weeks ago, but was discharged after a couple of nights because they needed space in the ward.

“There was no therapy or anything to help me. They didn’t even help me find an outside place to go to after and I was still sick when they let me out but they needed space because it was busy,” Rozek said.

Related: Bleak new record as 71,000 Americans died from drug overdoses last year

Many addiction treatment centers around the US have shut down or turned away patients because of the pandemic, as they struggle with financial losses and adhering to safety protocols. Rozek is currently in an outpatient program, but complained she was only given medicine to try to detox at home and in person support groups aren’t currently available.

“I’m genuinely trying but it feels like I’m stuck, and so do a lot of the other addicts I know,” Rozek added.

Mass layoffs, furloughs, isolation, and cuts to resources for recovering addicts have been cited as contributing factors to reported rises in opioid use and overdoses during the pandemic.

Based on data from the Overdose detection mapping application program, opioid overdoses increased in March 2020 by 18% compared to the same month in 2019, 29% in April 2020, and 42% in May 2020. According to the American Medical Association, over 40 states have reported increases in opioid related deaths during the pandemic, even as the US experienced a record of nearly 71,000 opioid related deaths in 2019.

“Drug users are doubly vulnerable right now. They are vulnerable in terms of increased risk of relapse, increased risk of misuse during the pandemic, but they’re also at increased risk for being infected by Covid and having adverse reactions to Covid,” said Dr Magdalene Cerda, of NYU Langone Health.

Cerda said states should be taking advantage of the loosening of regulations on opioid disorder medications methadone and buprenorphine to increase access to medication, increased funding for harm reduction services and loosening of restrictions by states for naloxone, an overdose reversal medication.

She also said social and economic benefits, such as sustained unemployment benefits, workplaces covering mental health and substance abuse care, are critical to preventing the worsening of the opioid crisis during the pandemic.

Dr Caleb Banta-Green, of the University of Washington, said some programs have struggled to adapt to loosening regulations on opioid use disorder medications in terms of ensuring easier access, which has been a constant struggle for opioid use disorder advocates even before the pandemic.

“Just like we’re trying to radically scale up a Covid-19 vaccine and get them to everybody, we should be radically scaling up access to treatment medications and getting them to everybody,” he said. “We have a health system with all sorts of rules and a mindset, a big misunderstanding, that people have to hit rock bottom or prove they are worthy and willing to receive treatment medications, which is absurd and dangerous.”

As opioid overdoses have increased, accessibility and capacity for substance abuse treatment has decreased due to Covid-19.

According to a September 2020 survey conducted by the National Council for Behavioral Health, 54% of behavioral health organizations have closed down programs and 65% had to turn away, reschedule, or cancel patients due to financial losses and reduced capacity during the pandemic. Even as some programs have enacted telehealth services, these require the internet and a phone or computer to be able to access.

During recovery periods, those struggling with opioid addiction can be at higher risk for overdosing if they relapse due to loss of tolerance and the unpredictability of resumed drug use, especially with the rise in the use of the synthetic opioid, fentanyl, in combination with other drugs.

Mark Morrison’s 26-year-old daughter Michaela, of York, Pennsylvania, was recovering from heroin addiction before Covid-19 hit. She was clean for a year and had a job. But during the pandemic she relapsed, obtained drugs laced with something that caused her heart to irregulate, and she later died at a local hospital on 3 September.

“It was a shock,” said Morrison. “She had just lost seven friends to overdoses in the span of two months, and I think the in-person recovery meetings being cancelled because of the pandemic contributed to her relapse.”

Luke Darmstadt, 25, died from a drug overdose on 2 June outside of Phoenix. He first became addicted to opioids while recovering from serious injuries sustained in a car accident in November 2016. He started buying pain medications off the street after becoming dependent and then taking heroin because it was cheaper.

Tina Mullican, Luke’s mother, explained he was in and out of treatment centers in the beginning of the pandemic in California, where he would be discharged after 30 days, relapse and re-enter a facility so the centers could continue billing insurance for the treatment. He got out of this cycle shortly before his overdose when he returned to Arizona while she was hospitalized due to surgery.

“He came here to see me, yet never had the chance,” said Mullican. “He went to a detox center to obtain a free flight. They bill the insurance for that. After detox, Luke went to see his old roommates he met in treatment in Arizona. That would be the last time anyone saw Luke alive.”

She explained the toxicology report noted Darmstadt had a lethal combination of fentanyl and meth in his system.

“I know my son. I talked to him that night. Luke never saw this coming,” she added.