Now, the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre will never be forgotten | DON NOBLE

There is a good deal of discussion and debate over Black history these days. What should be included, and which events have been downplayed or even somehow forgotten?

The most astonishing of the many events which were, it seems, forgotten or covered up is the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921. This was not a micro-aggression; this was a stupendous catastrophe.

That situation has been rectified. Victor Luckerson, raised in Montgomery and two times editor-in-chief of the Crimson White at the University of Alabama, has written "Built from Fire," a history of those events so monumental, so thorough, that no one can remain ignorant.

More: Amusing stories highlight everyday absurdities | DON NOBLE

The Greenwood section of Tulsa was a vibrant cultural and financial success. There were many businesses, a movie theater, clubs, a fine hotel, professionals of all stripes — doctors, lawyers and so on. Wall Street is not a perfect metaphor. There was no actual stock exchange, etc. — but there was prosperity and optimism.

Then disaster struck. In a minor, unimportant incident in an elevator in downtown Tulsa, a young Black man, Dick Rowland, perhaps lost his balance, perhaps touched the white elevator operator, Sarah Page. She perhaps screamed. The city paper distorted the incident into a possible attempted rape. Rowland was arrested and rumors quickly spread that he would be lynched.

(It is worth noting that this sequence of events—the "incident" between a young Black man and a young white woman was replicated in both the massacre in Rosewood, Florida, also written about at some length by Luckerson, in which the Black section of town was burned down and most Black citizens killed, and the Emmett Till murder in Money, Mississippi, where young Till may have whistled at or spoken rudely to the young woman behind the counter at the grocery store. In each of these three incidents, something like cultural paranoia erupted and murderous violence ensued.)

One of the of the important themes in Luckerson’s book is the determination in the Black community not to be passive victims. When this rumor reached Greenwood, a number of Black men, perhaps 50-75, many armed, marched to the jail to protect Rowland. I say marched because many were World War I veterans, and had military training.

As Luckerson reminds the reader, in both WWI and WWII, Black Americans enlisted, fought bravely and believed that this would surely improve their status when the conflict ended. After both wars, this was a grievous disappointment. The sight of Black men returning in uniform inflamed racists, and some Black veterans were actually murdered while still in uniform.

At city hall, a white mob also gathered. In a scuffle, a shot was fired, a white man was shot and within hours the virulent racism of white Tulsa manifested itself and a pitched battle ensued.

White police, instead of seeking to regain order, fraudulently deputized others and joined the mob in attacking Greenwood, with machine guns and possibly even incendiary bombs dropped on black Tulsa from an airplane.

The district was burned and looted: hotel, theater, businesses, gone. Estimates of deaths ran up past 175.

How could such an event drop out of history, out of popular memory?

The white city government was certainly happy to have this disgrace forgotten and many Black Tulsans, traumatized, did not speak of it.

But the Black press, especially the Oklahoma Eagle, covered racial violence, and kept the stories alive.

Luckerson could have ended his narrative in the 1920s, but he continued the story to the present, showing how Greenwood was, in a sense, attacked twice more, by perhaps well-intended urban renewal projects and then by the interstate highway system. Highways and housing projects get built somewhere — usually in the backyards of the poorest and politically weakest.

Reparations for injustices, also under discussion nationally, seem unlikely in cases dating back to slavery, before 1860, but the 1921 Tulsa events were well documented with dozens of pending lawsuits. Immediately after the massacre, property owners in Greenwood filed claims with their insurance companies. Many of those claims were rejected on the fraudulent grounds that there had been an insurrection in Greenwood. Appeals were made and the briefs and materials from those many claims still exist.

It will be interesting to follow these cases through the courts.

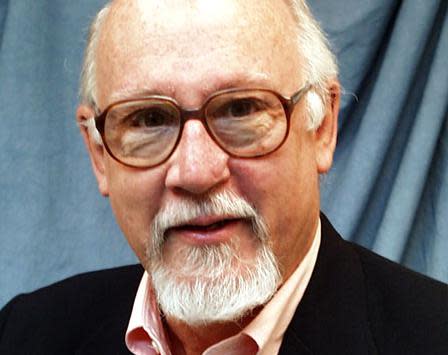

Don Noble’s newest book is Alabama Noir, a collection of original stories by Winston Groom, Ace Atkins, Carolyn Haines, Brad Watson, and eleven other Alabama authors.

“Built from the Fire: The Epic Story of Tulsa’s Greenwood District, America’s Black Wall Street; One Hundred Years in the Neighborhood That Refused to be Erased”

Author: Victor Luckerson

Publisher: Random House

Pages: 656

Price: $30 (Hardcover)

This article originally appeared on The Tuscaloosa News: Now, the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre will never be forgotten | DON NOBLE