By the Numbers: How Menopause Affects Different Demographics

As mysterious as menopause may seem to many women, in recent years, unprecedented research has provided us with more insight into this transitional period than ever before. Much of the credit goes to the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), which began in 1994 and continues to follow nearly 3,300 women in the U.S. as they age.

At this point, all the women enrolled in the study have gone through menopause, so the past couple of years have been fruitful, with research being published on just how significantly menopause symptoms affect women’s lives—and how the transition is generally more troublesome than we thought. But that’s not all. The SWAN study also uncovered the fact that menopause affects BIPOC women more than white women, especially when it comes to vasomotor symptoms (VMS), the technical term for hot flashes and night sweats.

“There was this conventional wisdom when we started the study that VMS lasted about two years, but what we learned is that it tends to last much longer,” says Siobán D. Harlow, PhD, SWAN study investigator and a professor of epidemiology and global public health in Michigan. “One of the other big things we learned was the difference in the symptom burden across different racial and ethnic groups. It’s been quite eye-opening.”

Here’s a closer look at the statistics showing how menopause affects BIPOC women differently than their white counterparts—and what you can do to get the relief you deserve.

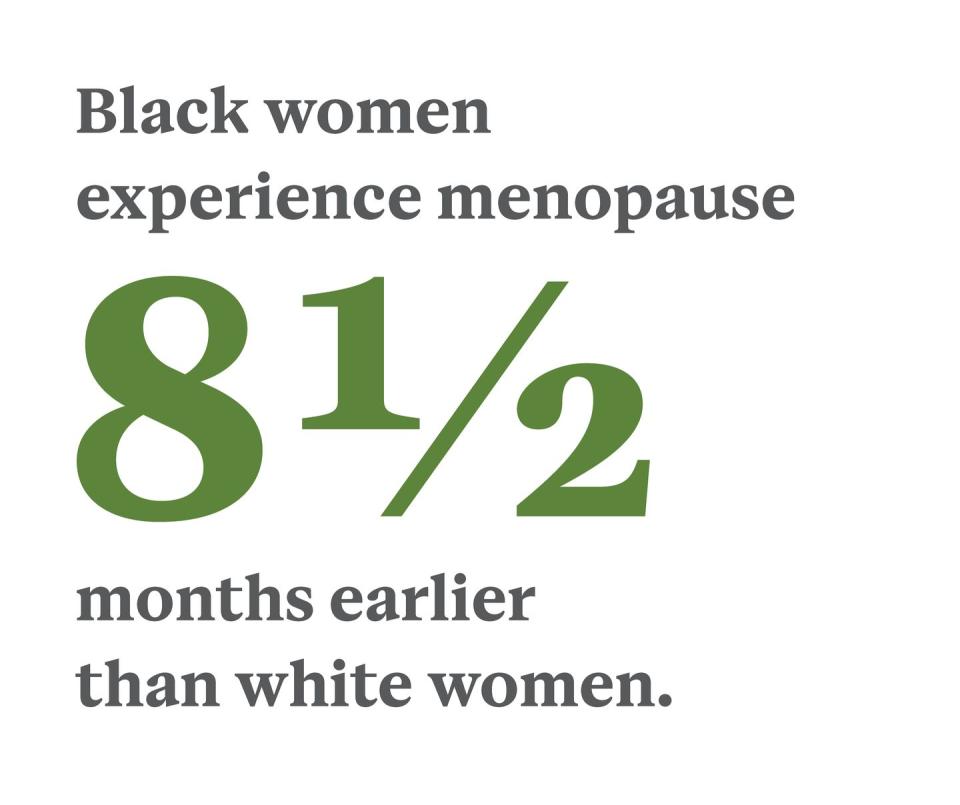

By definition, menopause is the culmination of 12 consecutive months following a woman’s final menstrual period. In the U.S., that’s most likely to happen at age 51 or 52 but can occur anywhere between 40 and 58, according to the North American Menopause Society. The women in the SWAN study entered menopause at the median age of 52, but Black women reach menopause at 52.17, an average of eight and a half months earlier than white women, who hit that milestone at 52.88 years.

“It’s still unclear as to why that is,” says Sherri-Ann Burnett-Bowie, MD, an assistant professor of medicine in Boston and one of the principal investigators for the SWAN study. “But there are definitely racial disparities when it comes to hot flashes and other symptoms of menopause.”

On top of the discrepancy in the average age of starting menopause, “there are definitely racial disparities when it comes to hot flashes and other symptoms,” says Burnett-Bowie. “It’s still unclear as to why that is.”

Researchers noted that Black women in the study were statistically more likely to have risk factors that increase the likelihood of VMS, such as smoking and obesity, but Burnett-Bowie says that doesn’t fully explain the disparity. “We’ve shown in SWAN that if your body mass index is higher or if you use tobacco, those are risk factors for hot flashes,” she says. “However, even after controlling for body mass index and tobacco use, there are still unexplained racial differences in duration and severity of hot flashes.”

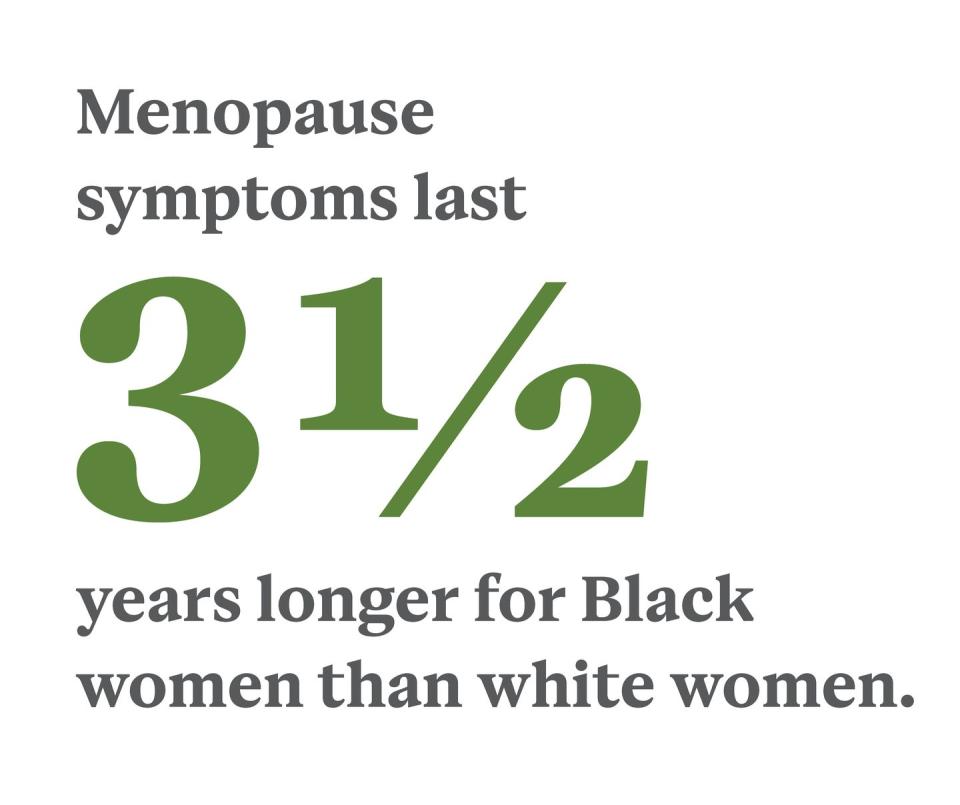

The fact that women of color start menopause sooner doesn’t mean that VMS and other menopause symptoms end any earlier for them. Symptoms in BIPOC women often begin earlier and last longer compared with white women. How much longer? An average of three and a half years more. Women of color report symptoms for an average of 10 years versus six and a half for white women.

“SWAN really helped us understand the patterns of hot flashes in Black, Chinese, Japanese, Latina, and white women,” Burnett-Bowie says. “We observed significant differences across the groups with regard to the number of hot flashes a woman has in a day, the duration they have them, and just how bothersome they are.”

Hot flashes and night sweats don’t just occur for a longer period in BIPOC women; they also happen more often in the short term. “Black women were much more likely to report very frequent hot flashes—six days a week or more—than white women were,” Harlow says. Their symptoms also tended to be consistently severe for many years, whereas hot flashes in white women are more likely to taper off throughout perimenopause (the period of time leading up to menopause) and menopause. “Black women, followed by Native American women, have the longest-lasting, most frequent, and most bothersome VMS of all the groups,” says Burnett-Bowie.

VMS in Hispanic women generally fell somewhere in between. “The Hispanic women in SWAN were more of a mixed cultural group, and many of the levels of symptoms depended on their specific ethnic subgroup,” says Harlow. “But overall, Hispanic women reported more hot flashes, and for longer durations, as compared with white women. In contrast, both Chinese and Japanese women were the least likely to report vasomotor symptoms or report that they were bothersome as compared to the other racial-ethnic groups in SWAN.”

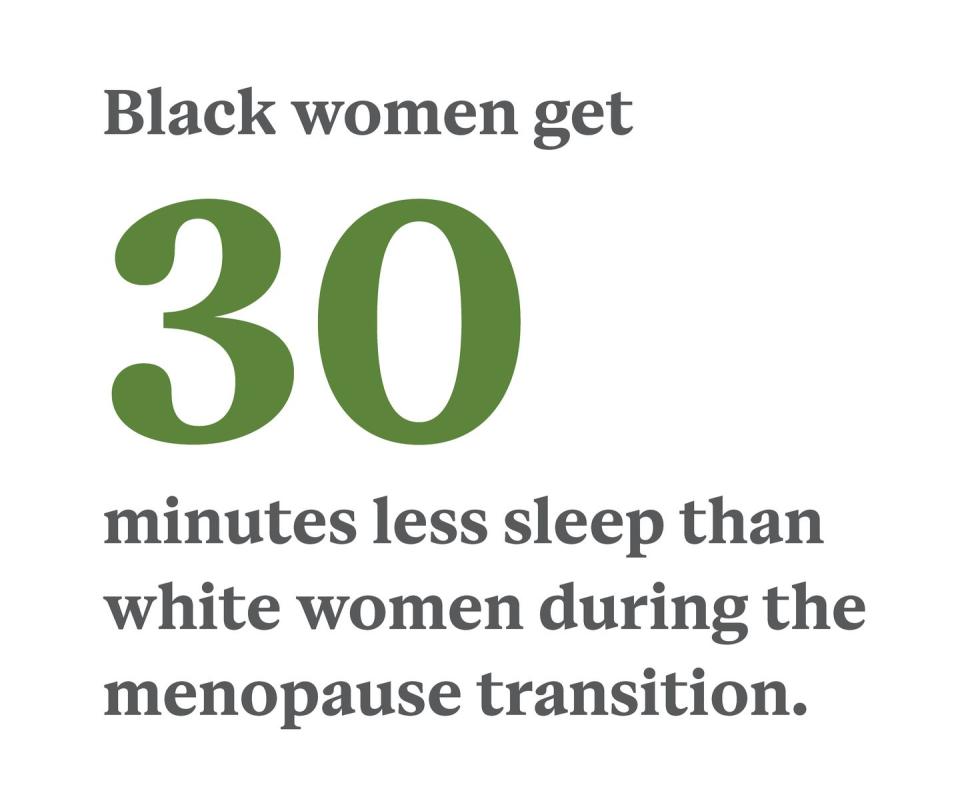

Because hot flashes can occur any time of day or night, it’s no surprise that they’re closely related to the amount and quality of sleep a woman gets during the menopause transition. The SWAN study found that women who reported frequent VMS—with Black women being the most likely to report—were twice as likely to have trouble falling, and staying, asleep, or waking early. Regardless of their VMS, Black women also got an average of half an hour less sleep per night than white women and were more likely than other racial groups to get less than six hours of sleep per night, which falls short of the National Sleep Foundation’s recommendation of seven to nine hours for optimal health in adults of menopausal age.

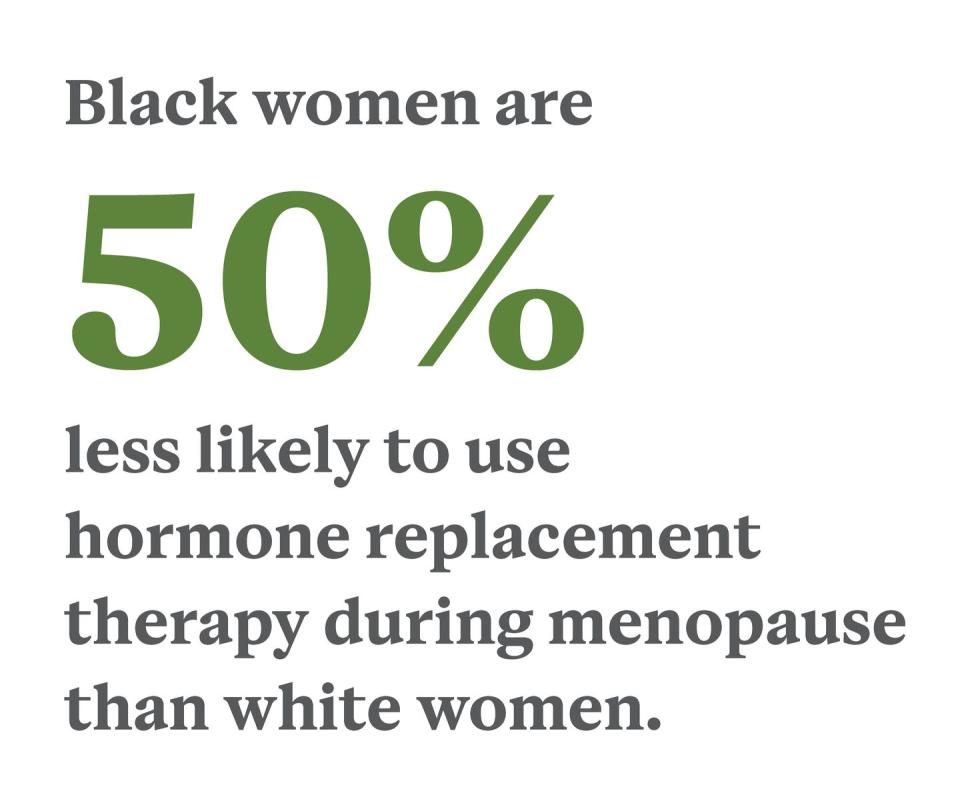

Given how hard BIPOC women are hit with VMS and other symptoms of menopause, they must be the most likely to use hormone therapy, right? Wrong.

“Black women [in SWAN] were about 50 percent less likely to be on hormone replacement therapy [than white women],” Burnett-Bowie says. “The why, though, is less well understood; is it a patient factor? A provider factor? A system factor?” More research is needed to isolate the exact reasons for this disparity, but she suspects systemic racism plays a significant role in Black women not getting the treatment they need.

Until the causes are addressed, Burnett-Bowie recommends BIPOC women advocate for themselves in their providers’ offices. “I think it’s really important for women to know that hot flashes can be quite detrimental and that there are both prescription and more natural approaches—acupuncture, meditation, and cognitive behavioral therapy—for treating them,” she says. “As a woman of color myself, the most important thing to remember is that there’s no issue that’s too small to discuss with your provider. If you feel as if your provider hasn’t answered your question, feel welcome to say, ‘I’m thankful for our conversation, and I want to talk more with you about X, Y, or Z because this is something that’s impacting me and I worry we haven’t thought through it enough.’”

If you still don’t get the answers you’re looking for, seek out a new provider. You can search for a certified menopause practitioner at menopause.org.

You Might Also Like