In the nurse's office: Schools' COVID first responders expect a spike, but with a shrug

The patient says her stomach hurts, but it’s not because she misses her mommy.

Nurse Colleen Panetta gives the third-grader the once-over in her office, downstairs at Church Street School in White Plains. No fever. The girl has had breakfast and is hydrated. Panetta tells the girl she’s OK and sends her back to gym class. Then she picks up the phone to update the girl’s mom.

“That’s what I’m here for,” Panetta tells the mom in the most reassuring voice she has. “It’s fine, honey, but if anything goes south, I’ll reach back out to you. All right, Mommy? Have a good day. Bye-bye.”

That’s what I’m here for.

That remains the mantra of the nation’s nearly 100,000 full-time school nurses, three years after the pandemic.

They are back to seeing scrapes and nosebleeds, coughs and the occasional fever — how things were before the COVID storm. That's when school nurses were deputized to bring their schools through a crisis the likes of which no one had seen.

Cough, cold, flu and allergy season has arrived, but on recent visits to two local schools — Church Street School in White Plains and Jesse J. Kaplan in West Nyack — echoes of the pandemic linger, the uninvited guest whose return is possible, even anticipated, with little more than a shrug.

School nurses are here for it all.

They’ve turned the page, but masks and tests are kept handy, just in case, and the nurses retain the muscle memory of what they’ve been through.

A second full-time job

They’ve been through plenty, says Maggie Racioppo, the nurse coordinator for 18 nurses at 15 public and private schools in White Plains, including Church Street Elementary School.

"It was really hell for them, to put it lightly,” Racioppo says. “Not only were we doing the nursing work that we have to do every day — where we see the students and we take care of chronically ill kids — but we wound up being a Department of Health employee because the Department of Health was mandating us to contact trace and to make sure that the parents were told if their children were exposed and to make sure you let the staff know if they were exposed.”

It was like a second full-time job, Racioppo says.

“We were here Saturdays, Sundays, nights, weekends, during storms calling people,” she says. “And if it was a Spanish-speaking family, it would be me calling, and my few Spanish-speaking nurses calling. It was quite a couple of years.”

Those years took their toll.

TLC and PTSD

Last year, the National Association of School Nurses surveyed nurses from all 50 states, the District of Columbia, the tribal nations and U.S. territories. School nurses had been on the front lines of a polarizing policy, often the face of that policy, and their efforts were sometimes met with resistance and hostility. The surveyed nurses reported:

48% felt bullied, threatened, or harassed;

39% experienced stigma or discrimination;

24% received job-related threats.

That treatment, and the uncertainty of those anxious early months, when PPE were in short supply and protocols were developed in real-time, left their mark. The nurses also reported:

30% reported symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder;

24% had moderate to severe depression;

22% experienced anxiety;

4% had suicidal ideation.

Terri Hinkley, CEO of the National Association of School Nurses, cited a report that more than 100,000 nurses left the profession in the last 12 months. That total included school nurses, "but I don't have the number for turnover among school nurses specifically,” she says.

The effect of what school nurses endured during the pandemic will linger, Hinkley says, but the uncertainty has abated.

“We know that COVID is not going away. We know that we're going to have to deal with it," she says. "It's not as frightening or as overwhelming as it was at the early stages of the pandemic.”

There will be outbreaks, Hinkley says, and the job for the school nurse is to limit the impact of those clusters within their school. That means monitoring the metrics available to check community spread — hospitalizations and COVID levels in wastewater — and having district policies about what to do if a student tests positive.

A manageable kind of busy

School nurses are busy again, in ways that feel manageable. They’ve got this.

Colleen Panetta’s Church Street School nurse's office is as busy as a Mamaroneck Avenue deli at lunchtime. No one is taking a number, but the patients wait their turn.

Each school day from 8 a.m. to 3:30 p.m., Panetta sees a steady stream of ills and ailments from a student body of 550 in grades K to 5, all requiring her attention and TLC.

“I see anywhere from 60 to 80 kids a day,” she says. “I see more kids than the local urgent care.”

The deluge of COVID data points is long gone — particularly since the pandemic emergency ended May 11, 2023. Racioppo is in regular touch with White Plains Hospital to track hospitalizations.

And Panetta is checking her numbers. She began at Church Street after 25 years in nursing, most of it at children’s hospitals, Blythedale and Maria Fareri. She looked at school nursing as a bridge to retirement after decades at bedsides. She began at Church Street on Jan. 14, 2020. Weeks later, the pandemic hit.

“I still keep an eye out for clusters in classrooms,” she says. “If there would be more than three cases within a classroom within a short amount of time, that's something I need to escalate to Maggie. We will send a notice home and there will be some sort of a follow up.

“I’ve had no clusters here. Not yet this year,” she said, knocking the wood on her desk. “Last year, we had a few after January and it was just a notice home and it came with very specific instructions” about at-home isolation and masking upon return to school.

There are boxes of COVID tests under her exam table. Nurses don’t swab students, but send home boxes of tests and ask parents to notify the school if a student tests positive.

There are masks in a basket for those who need one. In recent days, Panetta says, four students have asked for masks, not to protect themselves from others but because their parents suspect they might have had close contact with someone who was COVID-positive and they don’t want to spread the virus.

The return of masks, and the increase of coughing at Church Street doesn’t bring a wave of “here we go again,” Panetta said.

“I'm not triggered. It's the seasonal cough cold flu season on top with allergy. It's copy paste. It's the same thing every year. The RSV starts up in August. We prepare. Not that it's nothing to me, but it doesn't scare me.”

Nosebleeds, Pokemon and a pill crushed into yogurt

There are other things to focus on at the moment, seemingly every moment. Consider one 45-minute stretch for Panetta.

There is that third-grader whose stomach hurts, but not because she misses her mom.

Two girls come in. They tripped over each other on the playground. Panetta looks at their knees, puts some lotion on one elbow and sends them off.

There’s a girl with a nosebleed, a frequent Panetta visitor. “Sit and squeeze, honey,” the nurse tells her. The fifth-grader squeezes a bloody tissue to her nose, until the flow slows. Before sending the girl back to the classroom, Panetta dabs the blood off her shirt. “Peroxide takes the blood out,” she says.

Blake, a second-grader with diabetes, comes in with an aide to have her lunch portioned. Panetta cuts a turkey sandwich in half, slices a pear, calculates the carbohydrates and logs Blake’s glucose numbers in a book. Blake says she’s been telling her curious friends about diabetes. Panetta texts Blake’s mom, who texts back a thumbs-up on the glucose readings and the menu choice. With a “bon appetit” from Panetta, Blake is on her way to lunch.

Nicholas arrives to announce he has been coughing the past few days.

“My mom and dad have it under control,” the second-grader says, “but I’m still coughin’ and I’ve been hot and I’ve been snoozin’ in my class.”

“You were snoozin’ in class?” Panetta repeats with a big smile. “Hang on a second, mister.”

“It’s because I’m really hot,” Nicholas explains, as Panetta reaches for a thermometer.

His temperature is 97.3, cool enough to be sent back to class, hopefully not to return to his snoozin’ ways. But first Panetta looks down his throat and at his eyes and feels his neck, which makes the boy in the Pokemon shirt giggle. A good sign.

“All right,” Panetta says. “Nothing’s swollen. Nothing’s dripping. I think you’re going to survive today. You gotta drink your water and eat your lunch. Go eat, my love.”

On his way out, he passes a fifth-grader on her way in. There is no revolving door. It just feels that way.

“OK, pumpkin, you’re next. What’s up?” Panetta asks.

Her head is starting to hurt, she tells the nurse, who asks what she had for breakfast. (She hasn’t had breakfast.) She’s been thirsty all day, she tells Panetta, who asks where her water bottle is. (She doesn’t have one.) She tells Panetta she was late to school because she had to get a physical. The nurse diagnoses that wrinkle as the cause of the problem; it threw off her routine. She sends the girl to get a granola bar and some water and tells her to be sure to have lunch. “OK, lovey? Bye.” Panetta sends her on her way in under 90 seconds.

“As soon as they hit that door, I’m assessing,” she says in a brief quiet moment.

Most of what she sees in a day doesn’t rise to the level of a call home. That changes if there’s fever or vomiting, a barking cough that makes the child uncomfortable, or throat pain.

“Sometimes they come in here for just a little TLC, a happy hug. They want me to tell them ‘You’re fine. You’re OK. You can go back to class.’”

A third-grader needs her medicine, a pill that Panetta crushes into a yogurt cup. The girl leaves and is back in a second, having forgotten her books.

A first-grader named Alison is “a little bleeding” when she comes into Panetta’s office. A dab of ointment and a quick Band-Aid on the little elbow and 30 seconds later, she’s off. In the hall, the girl with the hurting stomach is back, lingering in Panetta’s doorway. She glances in furtively, then glides out of the frame, back to class.

In West Nyack, another revolving door

Meanwhile, at Rockland BOCES’ Jesse J. Kaplan School in West Nyack, nurses Suzanne Vogel, Eileen Vero and Julie Catalano tend to students whose needs are more acute: They have autism or cognitive disabilities or are medically fragile.

They come from Rockland, Westchester, Putnam and Dutchess counties. Some are high functioning; some are non-verbal; some are in wheelchairs or use other adaptive devices.

The Kaplan students range in age from 5 to 22, the age at which the state of New York declares them no longer students. (A recent change in the law raised the top age by a year.) Students can attend Kaplan 12 months a year for 16 years, in the same single-story building.

There is a soothing, dimly lit Snoezelen sensory room for calming, an aquatic center for physical therapy and a playground that is adaptive and accessible. Kaplan has a wing that looks more like a hospital than a school, with wheelchairs and adaptive devices at the ready.

There are nearly as many staff members, 270, as there are students, 325.

The nurse’s office is a natural Kaplan hub, where some students come to be fed through a tube and some students are given their medicine, where Band-Aids are affixed (and sometimes just as quickly removed), and where hugs are administered generously.

There’s an emergency cart filled with seizure medicine and EpiPens, a cart so important that it leaves the building during fire drills, along with the students and staff.

Being a Kaplan nurse means sometimes dashing down the hall with seizure medication to help a child in crisis. It also means making those reassuring calls home.

“When we call the parent, the first thing we say is ‘He’s fine,’” nurse Eileen Vero says. “When they get a call from the school nurse, they’re like: ‘What’s the matter?!’”

A high-five from Aidan

The parents at Kaplan School know more than their share of worry when it comes to their children’s medical conditions.

Some of the students, having had too much experience with hospitals already in their short lives, are naturally skittish with all things clinical, so the edges are softened in the nurse’s office. A feeding center — for those whose meals are given via a tube — has stuffed animals to disguise the pump. The nurses don’t typically wear medical scrubs.

A group of students arrives at the nurse’s office and a boy named Aidan makes his way into the room and gives a high-five. Vogel explains that Aidan was nervous about the nurse’s office, so his class takes a regular walk there, as a group, to make the experience familiar and non-threatening.

“Sometimes these kids have to go to hospitals for all sorts of things: EEGs, treatment, and it's all invasive and out of their norm and it's scary,” Vogel says.

The high-five is a milestone.

There are many new faces this year — about 50 new students, including three new kindergarten classes of eight students each. That means the nurses take walks of their own, to see the new children in their classrooms and match names to diagnoses to special needs.

“A big part of our job in every situation that goes on here is to keep everybody calm,” says Vogel, who is the lead nurse for Rockland BOCES. “We have the kids. They’re safe. If they have a seizure, we’re going to handle it. If any situation arises, we’re here.”

That’s what I’m here for.

Families, through COVID

Vogel, Vero and Catalano become trusted members of the students’ families, in relationships that can last 17 years, from when a kindergartner is dropped off for the first day until graduation, a banner Kaplan day.

"Our job is fun, it's challenging, it's rewarding," Vogel says. "The kids are fantastic, and we have such a wide range of students here, from the very severely handicapped to the more higher functioning autistic kids that come with their own uniqueness. And students with Down's syndrome that have these vibrant personalities that we get to know on a daily basis. They make coming to work fun. I don't think either of us ever has a day where we're like, 'I don't want to come today.'"

Because families rely so heavily on Kaplan, it was among the first Rockland schools to reopen from COVID, in September 2020, with half-school cohorts for a month and then all the students back.

Because nurses spend many more years with students than in a mainstream school setting, and because many of the students are at Kaplan for medical reasons, the nurses develop a sense for the students and know when something is amiss.

Vogel said there were a few COVID cases in September but nothing since. She laughs when she mentions that she has a connection at Good Samaritan Hospital in Suffern: Her daughter Dannielle is a nurse there and gives her a heads-up if COVID cases rise.

“They kind of creeped up there a little bit, but now they’re not,” Vogel said. “I’m thinking they’ll be back up around the holiday, on Thanskgiving and Christmas. We’ve had a couple of years now to see that those are spike times.”

Masks aren’t easy for those with medical or sensory issues, so most Kaplan students didn’t wear masks. Social distance was next to impossible for the Kaplan students, many of whom, Vero says, rely on big hugs to feel safe.

Their attitude, she says, amounts to: “‘I know mommy’s coming, but until mommy gets here, don’t leave me alone.’ You have to be their mother until their mother comes.”

If nurses suspect COVID, they can’t require a test, but will recommend one. A positive test means the student stays home five days and is masked for five days in school.

Kaplan has known a COVID loss. On May 16, 2021, student Levi LaSalle died after a long battle with COVID. The popular 19-year-old, dubbed the ‘mayor’ of Kaplan School, fell ill during spring break that April and didn’t return to school. There were no cases of COVID during that time period, BOCES said.

A glimpse into the nurse's office

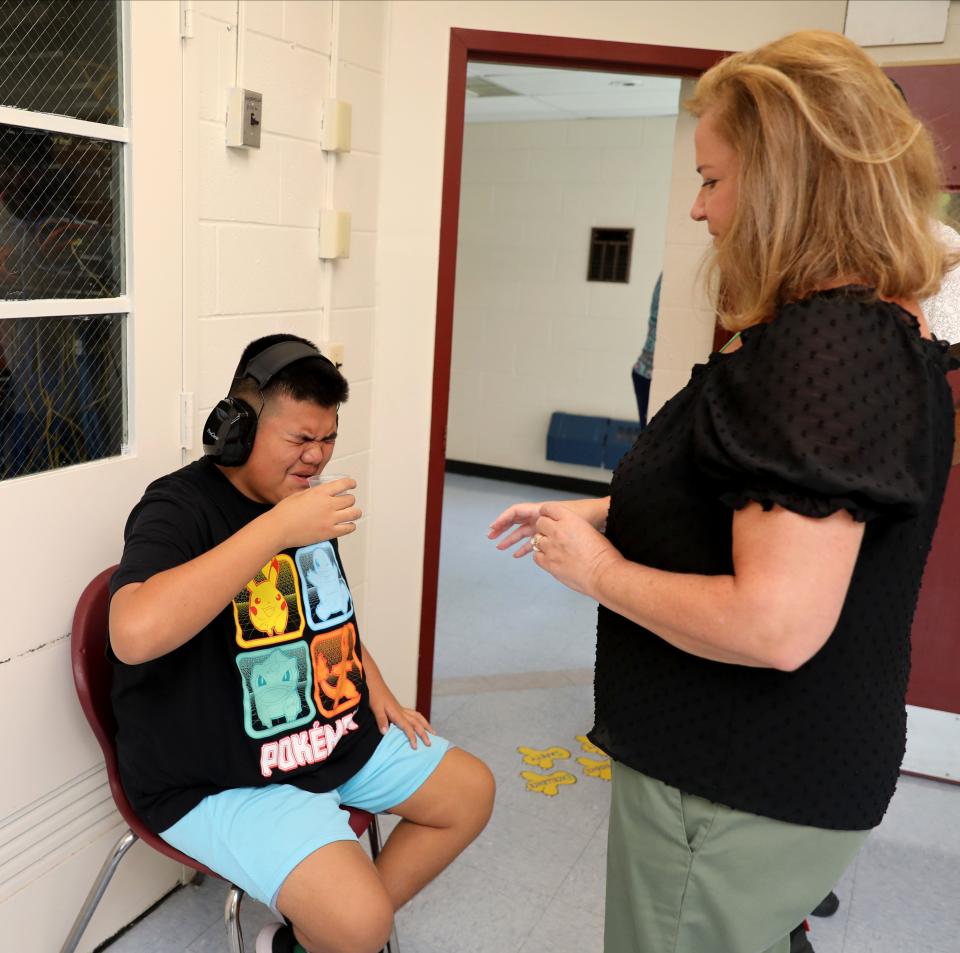

Juan, a bear of a 13-year-old boy, arrives at the nurse’s office wearing headphones. He circles the room, investigating, before presenting himself to Vero for his cup of medicine.

“Tell me when you’re ready,” Vero says.

“I’m ready,” Juan says, drinking the medicine and making a face.

“Eileen is Juan’s favorite,” Vogel says.

“OK, Juan, you had your medicine,” Vero says. “Time to go back to class.”

He circles the office again before leaving.

A boy named Connor – whose T-shirt has The Count from “Sesame Street” on it – walks in on his tiptoes, trailed by his aide. Connor has a stomachache, his classroom assistant says. He’s been crying and pressing his stomach. He wanted to go for a walk and made a bee-line for the nurse’s office, which is unusual for him. His appetite is off. Vero takes his temperature. Normal.

A call to his mom — “It’s Eileen from Connor’s school, he’s fine …” — leads to the conclusion that he might be constipated. “Moms always know best, so that’s why I’m calling you,” Vero tells Connor’s mother. “If anything changes, I’ll call you back. Otherwise, I think he’ll be fine.”

Emily arrives to be tube fed, the first of three feedings she’ll get today in the nurse's office. She has been at Kaplan since she was 5. She’s now 11 and could be at Kaplan another 11 years.

Vero has been a nurse at Kaplan since 2002. She gets emotional at the thought of the COVID year, when the graduating class were students she first encountered as kindergartners.

“To see them …,” she says, emotion preventing her from continuing. “It’s so heartfelt. The families, you build such a great relationship with them. I had to watch it on the screen and ... now I’m really bawling.”

Miles comes in with his aide, a skinned knee and a self-diagnosis.

“Band-Aid,” he says. “Band-Aid.”

As soon as the wound is cleaned and dried and the Band-Aid is placed, he peels it off.

“We have a lot of kids who love Band-Aids and a lot of kids who don’t,” Vogel explains with a smile.

Miles, apparently, is in both camps.

That’s what I’m here for.

Reach Peter D. Kramer at pkramer@gannett.com. Support this kind of reporting by subscribing, at www.lohud.com/subscribe.

This article originally appeared on Rockland/Westchester Journal News: COVID in NY: School nurses, first responders, expect spike in cases