This nursing home chain reported the highest COVID death rate. Then it deleted deaths.

Federal regulators will review the official tally of COVID-19 deaths at one of the nation’s largest nursing home chains after the company cut its reported death toll by an unprecedented 42% following a USA TODAY investigation.

Presented with USA TODAY’s findings that Trilogy Health Services had the worst death rate among its peers during last winter’s coronavirus surge, company officials said they discovered they had included deaths in their mandatory weekly reports that should not have been counted.

On Thursday, a chief medical officer at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services called the resulting changes “concerning.”

“CMS takes reports of data inaccuracy very seriously and will hold any bad actors accountable,” Dr. Lee Fleisher, the agency’s director of clinical standards and quality, said in an emailed statement.

The Midwest chain originally reported 772 deaths at 113 facilities from October 2020 through February 2021. The cut of 325 deaths, which the company said is based on federal guidance, drops its reported rate from highest to third-highest among the nation’s 10 largest nursing home chains.

Dying for Care: This nursing home chain stood out for nationally high death rates as pandemic peaked

Even more deaths could be excluded from the official tally for Trilogy, which operates homes in four states: Indiana, Kentucky, Michigan and Ohio.

Trilogy plans to submit another revision to its data for dozens more weeks beyond those analyzed in USA TODAY’s investigation. Damon Elder, a spokesman for American Healthcare REIT – the real estate investment trust that owns Trilogy facilities and shares in company profits – said Wednesday that he did not know the scale of those additional changes.

The revisions submitted by Trilogy deleted as many deaths as had been removed by a combined 13,500 other facilities. No other chain came close. Most large chains that revised their numbers added deaths, according to a USA TODAY analysis of the data posted on the CMS website.

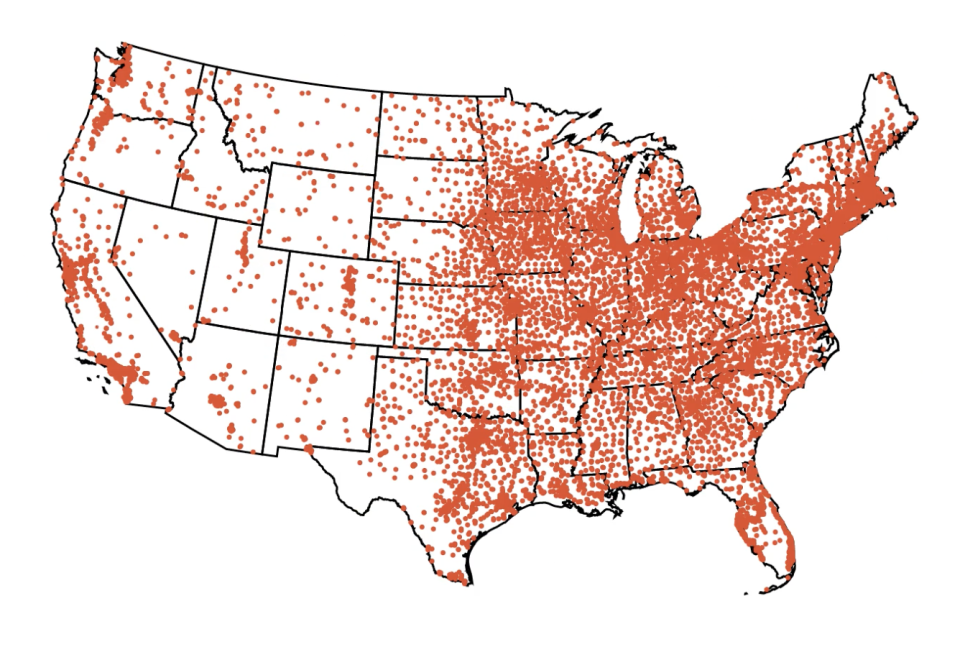

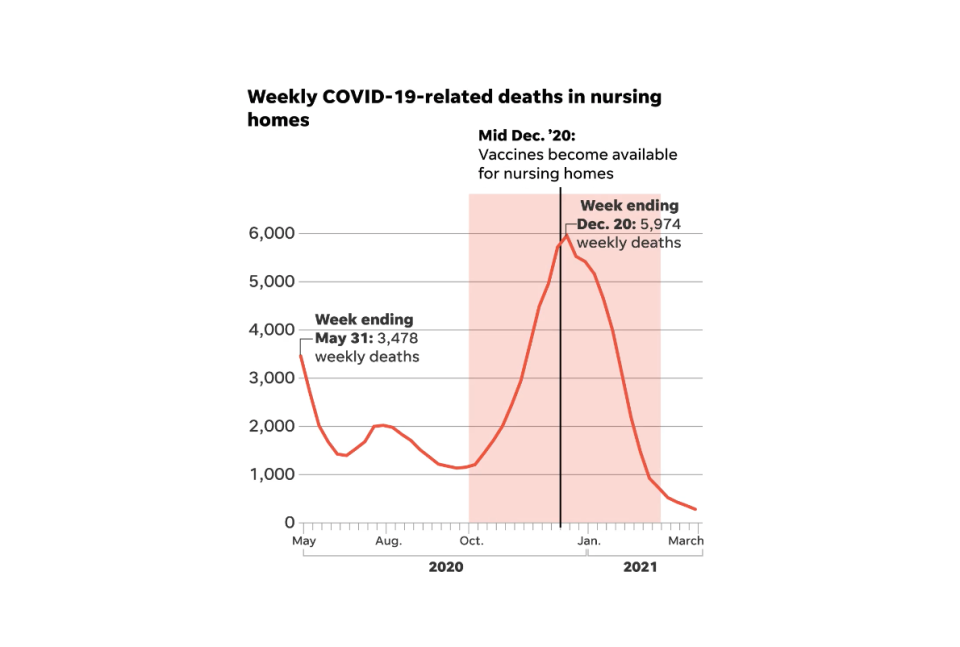

How U.S. nursing homes fared during COVID-19's worst surge

Last week, CMS spokesperson Mark Brager said the agency's policy is to accept revisions to self-reported COVID-19 case data without explanation or review. This week, Fleisher clarified that the agency would review Trilogy’s changes.

Federal rules adjusted for the pandemic allowed facilities to charge a higher rate for people with COVID-19 who were treated at the nursing home instead of being transferred to a hospital.

Asked whether the company’s revised accounting of COVID-19 cases and deaths would be compared to Medicare and Medicaid bills paid by CMS on behalf of residents, Fleisher described “some challenges” but did not specify whether such a review would take place. While COVID-19 tracking data was used to monitor cases and deaths in real time, it did not include the names of people counted, making it difficuilt to match with federal billing records that are tracked in a separate system.

Elder said Trilogy has not been contacted by either CMS or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention about its revisions. Since late May 2020, CMS has required facilities to submit weekly reports of new COVID-19 cases and deaths to the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN), a database run by the CDC.

Explore: When does a nursing home COVID-19 death count? It's complicated.

The government has used the information to award billions of dollars in COVID aid as well as target inspections and identify facilities that might need extra support during outbreaks.

Some academic researchers, who have relied on the data to study how and why COVID-19 has killed more than 140,000 people in nursing homes, called on government officials to step up after learning of Trilogy’s extensive revisions.

David Grabowski, a health care policy professor at Harvard University medical school who studies nursing home performance, called Trilogy’s revisions “suspicious.”

Grabowski said there “should be some consequences” for submitting incorrect data to the national COVID-19 reporting system because of how important the system is to government officials and researchers who use it to understand the pandemic.

“Either they are admitting they submitted bad data or they are going back and altering the data to make themselves look better,” he said. “I don’t like either of those outcomes and both of them speak to the need for increased oversight and accountability.”

Charlene Harrington, who has studied nursing home quality for more than four decades, agreed that CMS should thoroughly investigate.

“I really don't see why CMS would let nursing homes revise their reports without some specific evidence that documents the information,” said the professor emerita at the University of California, San Francisco.

A report from the inspector general of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, which examined the early days of the federal reporting, found the majority of nursing home submissions appeared complete. An updated evaluation is due to be published in September.

Federal regulators “should be asking questions” about significant revisions, such as the one made by Trilogy, said Karen Shen, a Harvard Ph.D. candidate who led a study estimating at least 16,000 people died in nursing homes before mandatory reporting.

Fleisher, the CMS official, said reviews of NHSN submissions are limited by “capacity challenges,” so they typically take place only after the agency receives an inquiry or complaint. It is one reason, he said, “why President Biden’s budget calls on Congress to increase CMS inspection resources by nearly 25%.”

Vince Mor, a professor at the Brown University School of Public Health, said he is concerned that the CDC and CMS do not actively audit or otherwise verify data submitted to the NHSN.

“It is much easier to just blame the incompetency of the facilities reporting,” he said. “It is a miracle that any of the data make any sense at all.”

Another person hoping for government action after Trilogy’s revision: Shana Driver, whose mother died in a Trilogy-owned nursing home in Indiana last winter.

A 103-degree fever suggested and two positive tests confirmed Sue Miller had COVID-19, Driver said, remembering what she learned during conversations with nurses. Two weeks later, the family was approved for final bedside visits inside the COVID-19 ward.

Miller died on Day 4 of their vigil, Dec. 21, 2020, while her son-in-law sat at her bedside playing her favorite Bee Gees songs.

Sue Miller’s death certificate lists COVID-19 pneumonia as the cause of death. Originally, Trilogy reported four deaths that week, all from the pandemic virus. Its revised data shows none.

“I don’t know how they can just erase that,” Driver said. “That just makes me angry. … They are just trying to erase people.”

Elder, the Trilogy spokesman, declined to comment about specific cases. He noted that it was common for deaths or cases to be reported in subsequent weeks rather than the weeks they occurred. Trilogy reported five COVID-19 deaths the week after Miller died. Federal rules require facilities to accurately link cases and deaths to the week they happened.

The revisions were spurred by a first-of-its-kind data analysis by USA TODAY, which identified Trilogy Health Services as reporting COVID-19 death rates twice the national average – 7 per 1,000 residents – during the pandemic’s worst months in nursing homes.

With its revised death numbers, Trilogy ranked No. 3 out of the nation's Top 10 chains –behind the Good Samaritan Society, a nonprofit chain operated by Sanford Health, and Signature HealthCARE, a for-profit chain, USA TODAY found in an updated analysis.

In a written statement, officials from the Good Samaritan Society and Signature HealthCARE did not explain why their average death rates were higher than other large operators, many with facilities in the same states. The companies critiqued the USA TODAY analysis for focusing on the months before vaccines were widely available – when almost half of all COVID-19 nursing home deaths occurred.

“Our nursing homes were dealing with a once-in-a-century pandemic and a virus that disproportionately targets older adults and those with underlying conditions. This is the very population the Good Samaritan Society is called to serve,” President and CEO Nathan Schema wrote.

SignatureHealthCARE’s statement described USA TODAY’s work as part of a “continual barrage of negatively focused media,” detailing the extra expenses the company incurred to provide care during the pandemic and an infection control program launched in early 2021.

“Throughout our ongoing battle and crusade against COVID-19, the long-term care and skilled nursing healthcare sector as a whole has been attacked, and not just by the virus,” read the statement sent by Communications Manager Ann Bowdan Wilder. “Unfortunately, and quite egregiously, our sector has become the maligned focus of media and other high profile, predatory platforms for negative stories, unbalanced reporting, targeted blame, and inflammatory finger pointing.”

Trilogy leaders have disputed USA TODAY’s characterization of the company's facilities compared with its peers, arguing that Trilogy officials had overcounted COVID-19 deaths while many nursing homes undercounted them.

“Reporting practices in several of the states where we operate have recently come under scrutiny, specifically regarding under-reporting of cases and deaths. Therefore, we feel any comparison data with our competitors at this point is unreliable,” Trilogy CEO Leigh Ann Barney said in a video message sent to the “Trilogy family” days before USA TODAY published its findings.

Good Samaritan Society and Signature HealthCARE described their own reporting to the NHSN as complete. Signature operates facilities in some of the same states as Trilogy.

The Indianapolis Star, part of the USA TODAY Network, has extensively reported on deaths at nursing homes in Indiana, including some that state officials said were reported accurately to the federal system but not to the state. The Ohio Health Department similarly audited death reports and found hundreds in nursing homes that had not been counted in its state tally, but it is unclear whether those same deaths had been accurately reported to federal regulators.

Rachel Reeves, a spokesperson for the American Health Care Association, cited the inspector general's audit as proof that facilities, by and large, complied with COVID-19 reporting requirements. That report found 95% of the nation’s more than 15,000 nursing homes completed all required survey fields with no obvious errors, such as wildly unrealistic numbers, although the tallies were not audited.

“Nursing homes come under frequent ‘scrutiny’ as the representative at Trilogy mentions, but that does not necessarily mean underreporting occurred,” wrote Reeves, who represents the largest industry association for nursing homes.

Nursing homes have been the focus of increased inquiry amid the pandemic. One federal OIG report found 1 million of the nation’s 3 million nursing home residents contracted COVID-19 in 2020. The White House is preparing to use its executive authority to tighten industry regulations while some members of Congress say they want to dig into the corporate owners and operators.

'Profiteering, cold-hearted': Nursing home owners should be investigated, congressman says

In a report released last week, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine called for federal officials to expand the government’s tracking and regulation of nursing home companies, highlighting private equity firms and real estate investment trusts as models that should be evaluated.

A majority of Trilogy’s buildings are owned by a real estate investment trust, American Healthcare REIT.

In addition to collecting rent, American Healthcare shares profits from Trilogy's operations – a model allowed under a federal law revised in 2008. The concept was permitted earlier for REITs outside health care to allow them to offer basic services for their properties, such as cleaning. American Healthcare REIT appears to be the first large trust to use RIDEA, or the REIT Investment Diversification and Empowerment Act, in nursing homes.

With complex ownership structures, which often involve a web of related businesses, savvy owners can reduce taxes, shield money from potential lawsuits and route profits up to the top of a corporate chain even as individual facilities report operating in the red. This makes it difficult, experts said, for the federal government to understand how much of its nursing home funding, paid through Medicare and Medicaid claims, actually goes to care as intended.

Contributing: Letitia Stein

Jayme Fraser and Nick Penzenstadler are reporters on the USA TODAY investigations team. Contact Jayme at jfraser@gannett.com, @jaymekfraser on Twitter or on Signal at (541) 362-1393. Nick can be reached at npenz@usatoday.com, @npenzenstadler on Twitter or on Signal at (720) 507-5273.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Nursing home COVID deaths: One chain deletes 42% of its death tally