How a NY high school student set the record straight for a Black Civil War vet

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Buried under a weathered gravestone in Milltown Rural Cemetery in Brewster, New York, lies Pvt. Francis "Frank" Oliver Myers, a Black Union soldier who fought with the famed 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment in the Civil War.

For over 130 years, historical records showed that Myers was from Paterson, New Jersey. But a Brewster High School senior, Ellen Cassidy, who passes Myers' grave each day, discovered that his true hometown was Patterson, New York.

She is setting the record straight and honoring Myers in the process.

It's "kind of a 'Hidden Figures' story," Cassidy, 17, said, referencing the 2016 film and book that shed light on the African American women who worked for NASA as mathematicians during the space race. "Being able to tell that story is really special to me."

Cassidy's interest in Myers stemmed from passing his grave on the drive to school every day. Her mother, Putnam County Historian Jennifer Cassidy, suggested she find out more about him.

In her research, the younger Cassidy quickly found the error — history books showed Myers to be from Paterson, New Jersey, but military records showed he was really from Patterson, New York, a town in northeastern Putnam County.

Cassidy caught the error at her dining room table. She was confused at first about how the discrepancy could exist.

But then it was exciting, she said. "It's kind of like finding a typo in a book."

Her discovery caught the interest of renowned historian Drew Gilpin Faust, a former president of Harvard University, who Cassidy emailed for guidance on how to get the word out about her discovery. Faust offered some advice and connected Cassidy with the Massachusetts Historical Society.

"It was clear she'd already done quite a lot of work," Faust said.

Faust told her that when historians need to get the truth out, they publish their findings so they become part of historians' general discourse. The hope is that doing so "persuades people of what the right rendition of the past is."

Correcting even the smallest details is important, Faust said: "The fact that he comes from one place or another may have significant ramifications for the community he came from, the community he influenced, the way he grew to be who he was ... If you get that wrong, then you shut off one avenue of understanding and you also distort an important part of what has happened in ways, that if they can be corrected, should be corrected."

'Forward fifty-fourth!'

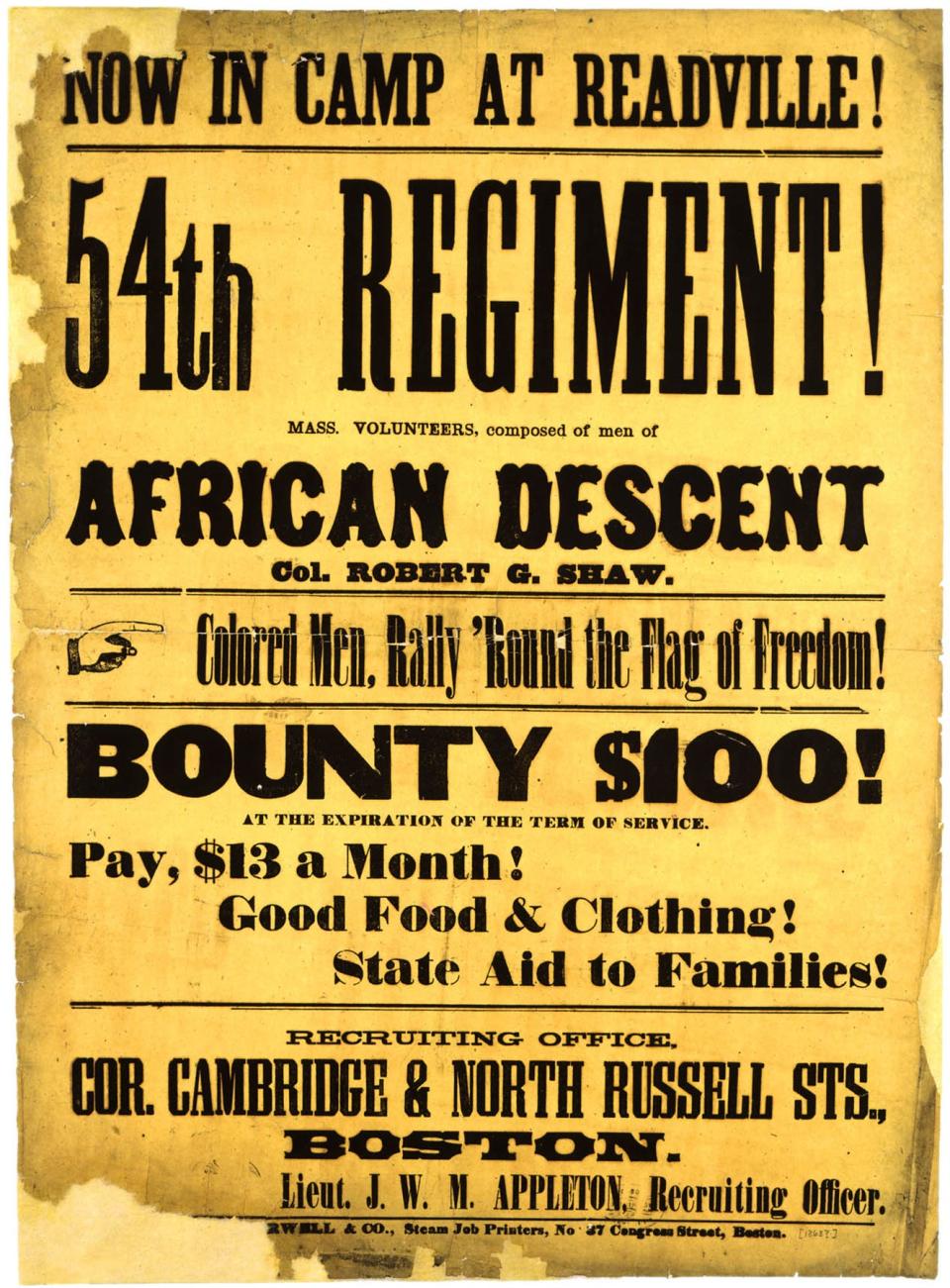

At 23, Myers joined the Union Army in Massachusetts, becoming part of the 54th Regiment, the first African-American regiment formed by a northern state. Led by Col. Robert Gould Shaw, the 54th became known for its valor in the battle to take Fort Wagner in South Carolina in 1863.

The battle was portrayed in the 1989 movie "Glory," in which Denzel Washington played a private and Morgan Freeman a sergeant major in the 54th. The epic battle scene shows Matthew Broderick as Shaw, leading his soldiers to a gruesome battle, shouting "Forward fifty-fourth!"

Through Cassidy's research, she found Myers was severely wounded in that very battle. One of his arms was paralyzed and he sustained injuries to his head and back. He was next to Shaw when Shaw was shot and killed as he raised his sword, shouting the famed phrase. Myers fell shortly after.

Myers was hospitalized for months, promoted to corporal and discharged in February 1864. He returned home to Putnam County, settling in the town of Southeast. Cassidy found his obituary in the Putnam County Courier dated May 19, 1866.

During the Civil War, Myers was one of 1,000 Black men from across the U.S. to serve in the 54th, said Elyssa Tardif, director of education at the Massachusetts Historical Society.

The battle was a Confederate victory, but "When news of the battle reached home, the unit which had been the target of so much attention, publicity, and skepticism finally earned the respect it deserved," Tardif said. "Even so, the soldiers had to fight for the pay they had been promised — the same as their white peers — and refused to take any pay until they had received full compensation and back pay."

Honoring a hero

Because of Cassidy's discovery, both the National Park Service and the National Gallery of Art corrected Myers' hometown in their records.

Cassidy wrote about Myers, her discovery and the 54th Regiment for the New York Almanac. Through the Bob Palmer Project, a local effort to place flags on veterans' graves every Memorial Day, Cassidy will ensure Myers and another Black Union soldier buried nearby will have new flag holders.

She's also working on getting a historical marker about Myers in Brewster.

"He is Putnam County’s hero who fought for liberty," Cassidy wrote in her piece for the New York Almanac. "His headstone marks a grave of glory."

Cassidy, who is student government president and captain of her field hockey team, is interested in studying history and film studies in college.

"I don't know what she's going to do next," Faust said. "I hope she'll become a historian."

Contact Diana Dombrowski at ddombrowski@gannett.com. Follow her on Twitter at @domdomdiana.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: High school student sets the record straight for a Black Civil War vet