NY investor behind Piney Point ran hedge funds, a blueberry farm and string of Hooters

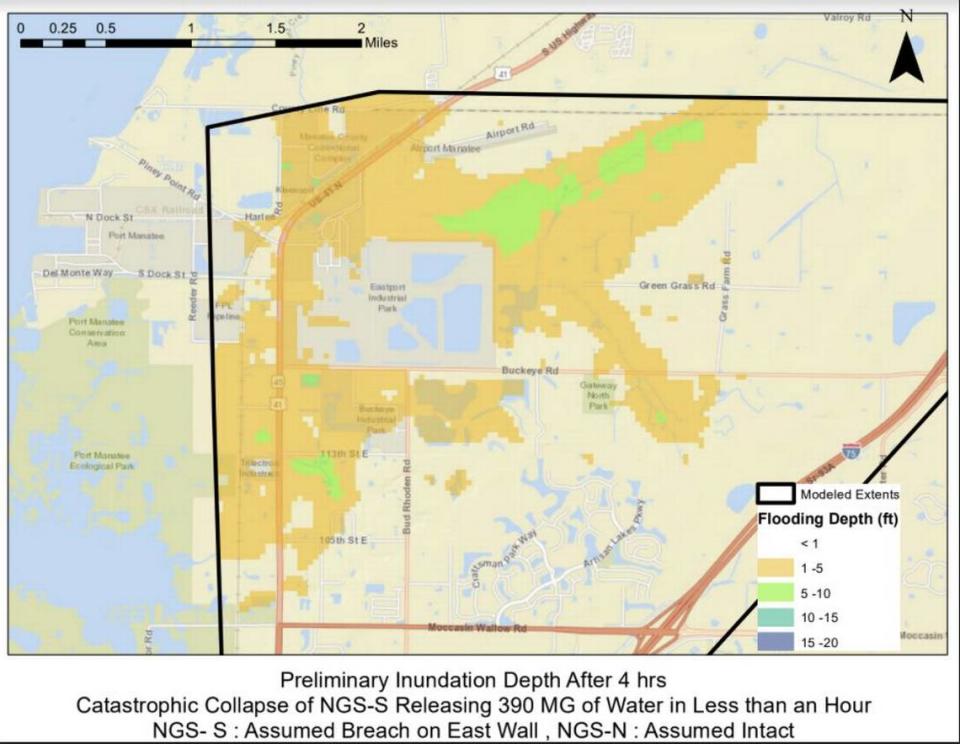

The state has vowed to hold HRK Holdings — owner of the troubled Piney Point phosphate plant site leaking polluted wastewater — “accountable” for a still-unresolved environmental crisis that has forced hundreds of evacuations and threatens to devastate marine life in Tampa Bay.

That will be a major legal challenge.

“I’d love to string them up, but the reality of the situation is they have one shell company after another. These guys are rich and smart and they know what they’re doing,” said Manatee County Commissioner Kevin Van Ostenbridge. “It’ll be like getting blood out of a turnip. We’ll never get a nickel out of them.”

Since going belly-up after a massive spill in 2011, HRK has been operating in bankruptcy, contending it could not afford the millions needed for the previous cleanup. Since the rupture of a retention pond wall at the long-shuttered plant last week, the company has said nothing about how, or if, it will handle the latest cleanup bills. Neither has the wealthy New York investor that Florida public records identify as HRK’s principal owner — William “Mickey” F. Harley III, a Wall Street executive and former hedge fund manager with a history of snapping up bankrupt or struggling companies.

His list of past and present investments is long and, to say the least, eclectic. At one point he owned a series of Hooters franchises in Long Island, had a seat on the board of lingerie company Frederick’s of Hollywood, served a stint as president of a uranium mine in Namibia, and most recently, began a foray into the marijuana industry.

Forbes, in 2004, called him “a vulture,” an investor who specializes in swooping in on dying and troubled companies and making a profit anyway. In 2006, the Wall Street Journal highlighted the time he bested legendary financier Warren Buffet himself in a deal over Seitel Inc, a then-bankrupt seismic data company.

What is Piney Point? Here’s what to know about the toxic industrial site

Nowadays he serves as CEO of Greenrose Acquisition Corp., which just announced it plans to buy four cannabis companies, where he describes himself in his bio as an “agriculturist at heart.” His mini-resume on the site includes serving as president of an organic blueberry farm, running “the largest vertically integrated pecan company in the world,” and managing a handful of hedge funds.

It doesn’t mention his stake in Piney Point, an abandoned phosphate plant with a long history of environmental problems.

Harley’s long business record also is dotted with a few lawsuits — including one that accused him of improperly using his hedge firm’s money to bail out the phosphorus mine after another spill years ago.

Harley did not immediately respond to requests for comment left with his current place of business, a cellphone number affiliated with him or with lawyers who have previously represented him. Jeff Barath, the site manager for HRK who has been the company spokesman during efforts to control the leaking wastewater pool, did not respond to a request for comment.

This threat to the public appeared to be easing Wednesday morning after Manatee County lifted its evacuation order Tuesday afternoon, allowing the 137 residents to return to their homes while workers still used pumps and vacuum trucks to lower water levels at Piney Point. But there is still risk to Tampa Bay and a question about who will pay a bill that will run into the tens of millions or more for a permanent solution to the abandoned plant’s sprawling wastewater ponds.

Bonnie Malloy, an attorney with Earthjustice who previously worked with DEP, said it can be tough for the agency to find a “living, breathing, financially viable person” to pay for cleanup in cases like these. It’s also hard to build a court case strong enough to cut through layers of shell companies and limited liability companies shielding investors and force them to pay.

“It’s definitely a pervasive problem in Florida and elsewhere,” she said. “The corporate structure does allow protection of the principal and they do take advantage.”

HRK buys Piney Point

Harley came onto the scene in 2006, when his company HRK Holdings bought the bankrupt former phosphate mine for $4.3 million from DEP, which had been holding the site ever since the previous owner, Mulberry Corp., went bankrupt in 2001.

DEP had planned to use taxpayer money to close the site, but HRK approached the agency with a plan to buy the property for the sole purpose of storing dredging disposal from Port Manatee.

A longtime fertilizer industry figure, Art Roth, was the catalyst behind the new buyers. He found Harley, Gary Kania and Scott Rosenzweig, and the three investors formed HRK, a combination of their initials. Roth was appointed their local representative, and he and CEO Jordan Levy were the local faces of the business for many years.

However, Bradenton Herald-obtained emails show Harley was directly involved in discussions with the port over Piney Point in 2011 just before the infamous spill into Tampa Bay. He was identified as chairman of HRK in a number of new reports over the next few years. And in state corporate records updated in February of this year, he is listed as the “managing member” of the company, but neither Kania nor Rosenzweig are listed.

When HRK Holdings was first incorporated in 2006, documents filed to Sunbiz said official mail should be sent to Mellon HBV Alternative Strategies, a limited liability company based in New York with the same three managers as HRK, including Harley.

Mellon HBV Alternative Strategies, a hedge fund management unit, was a subsidiary to a large hedge fund, Mellon Holdings, that managed almost a billion dollars in assets at the time. In December 2006, the Bank of New York bought Mellon Holdings and sold Mellon HBV Alternative Strategies to Harley for an undisclosed sum, Pensions&Investments reported.

Harley renamed the firm Fursa Alternative Strategies. Two years later, mid-financial crash, the asset management firm announced to all its investors it was shutting down the business.

But a lawsuit filed in 2011 by The Claude Worthington Benedum Foundation, which had invested $2 million into the hedge fund, said Harley didn’t return its money. The suit accused him of continuing to run the business out of the basement of one of his Hooters franchises, a claim he denied, and funneling the foundation’s investment into buying 8 million stocks of Frederick’s of Hollywood, a lingerie company he co-owned at the time, as well as the cleanup at Piney Point after it spilled 170 million gallons of toxic water into Tampa Bay’s Bishop Harbor.

The human development charity argued that instead of paying his investors back, Harley continued to pay his own salary, as well as hundreds of thousands of dollars to his brother for no apparent purpose and at least $5.6 million to other investors who were his friends or business acquaintances, Trib Live reported.

Harley’s own lawyer, Patrick Cavanaugh, acknowledged in court that Harley was unable to explain many of the payments or account for where the money went.

“It’s not the greatest bookkeeping,” he said, according to Trib Live.

The lawsuit ended in a sealed settlement, Newsday reported.

The 2011 spill

When purchasing the property in 2006, HRK holdings made several agreements with DEP on how it planned to protect the site from further environmental disasters.

As usual for all other former phosphate mines, DEP asked HRK to cover the exposed lining with a layer of dirt to keep it protected from the damaging rays of the sun, a $4 million expense.

But for the first time, the agency decided to waive the requirement because of HRK’s planned business deal with its neighbor, the Port of Manatee. Instead, DEP required the Port and HRK to carry a $2 million insurance policy, which they never purchased, according to Herald reporting.

The Port wanted to dredge a new berth, part of a $200 million expansion to allow for larger cargo ships. And they wanted someplace to put the dredge material. HRK offered the gypsum stack ponds at Piney Point, a deal that would be cheap for the county and profitable for the former phosphorus mine, which was busy leasing space on their land in a new industrial park called Eastport Terminal.

Will a deep well put an end to Piney Point? State officials say funds are available

DEP officials told the Bradenton Herald they expected the dredged material to serve as a cover for the lining, but the dredging didn’t get started until 2011, leaving the lining exposed for years.

A Bradenton Herald investigation revealed that HRK discovered and fixed a 6-inch tear in the liner in 2011, just before dredging got started. At the same time, a study commissioned by HRK and obtained by the Herald found that the liner’s seams weren’t built properly and the structure already had stress cracking from its sun exposure.

Despite that knowledge, which Bradenton Herald reporting showed HRK never shared with Manatee County officials, 1.1 million cubic yards of material from the Port of Manatee’s Berth 12 project were soon dumped in the same pond, a purpose former phosphate mines had never served.

One month after the new material was dumped into the pond, the liner ripped again — sending 170 million gallons of toxic water in Tampa Bay’s Bishop Harbor and leading to a flurry of lawsuits.

HRK sued the 10 contractors that designed, installed and analyzed the liners for the gypsum stacks. A Michigan contractor sued Manatee County Port Authority for $4.8 million for the ensuing delays in the construction of Berth 12. Both parties eventually agreed to a $3.3 million settlement. And the Port sued HRK for $12 million.

Florida Senate wants to find $200 million to clean up Piney Point once and for all

It was too much for HRK Holdings. The company filed for bankruptcy. In federal court documents, the company said it couldn’t afford to pay for the necessary environmental cleanup after the devastating spill into Bishop Harbor the previous year.

Facing $26 million in debt to more than 60 creditors, HRK started selling off chunks of the 675-acre Piney Point site. The first 30 acres went to Air Products and Chemicals for $5.8 million in 2012. Utah-based Thatcher Chemical purchased 8 acres for $1.57 million in 2013. Allied Universal Corp, a Miami chemical manufacturer, purchased 572 acres for nearly $7.9 million in 2014.

The bankruptcy case closed in 2017, and a federal document filed that year said that HRK Holdings had resolved all claims from its creditors except for the $12 million claim from Manatee County Port Authority.

Bradenton Herald reporter Jessica De Leon contributed to this story.