NY takes a step to solve homelessness. Is this a blueprint for the US? | Mike Kelly

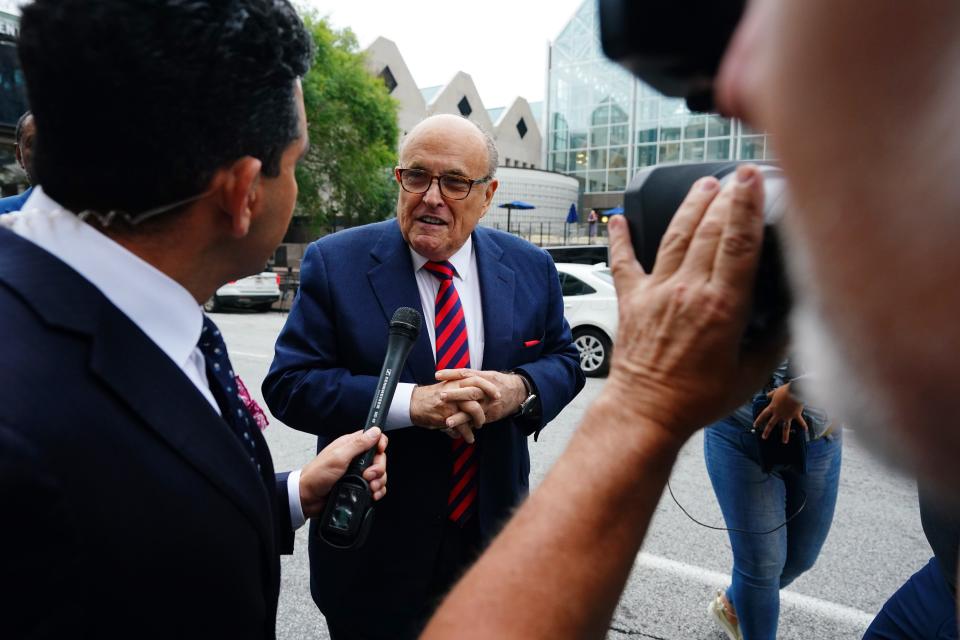

Eric Adams, the moderate Democrat and former police captain who took over this year as New York City’s mayor, will never be mistaken for Rudy Giuliani, the Republican who rose to national prominence as the city’s mayor before throwing himself at the disgraced feet of former President Donald Trump.

But Adams ripped a page this week out of Giuliani’s mayoral playbook for dealing with homeless people.

Long before Giuliani became a hero of 9/11 — and was dubbed “America’s Mayor” — and before he sunk to his political knees by spreading lies and baseless conspiracy theories about a “stolen” election that Trump lost, he took a courageous stand on homelessness.

Giuliani said homeless people have no right to find shelter on the sidewalk, in parks and other public spaces.

Progressives were aghast — of course. Some of New York’s well-heeled liberals even suggested that people who spend their days mumbling to themselves and forgetting how to tie their shoes actually had a Constitutional “right” to live in public spaces. It was liberalism at its worst — completely clueless to common sense, captive to theories and solutions that worked well in graduate school dissertations but failed miserably in the real world.

Giuliani smartly ignored the progressives and cleaned up New York. Suddenly Central Park and other city parks became safe for children to play in. And remember the so-called “squeegee men” who swarmed motorists at traffic lights on Manhattan’s West Side, wiping windshields with dirty rags and demanding payments that seemed more like ransom? Giuliani told them to get lost — and they did, thankfully.

New York City came back to life. Business boomed. Tourists flocked in. The subways rebounded.

But the roots of homelessness went unsolved.

Giuliani was not perfect. He was far too brutish at times. And, yes, New York’s police overstepped many boundaries, especially in their “broken windows” campaign, which unfairly targeted Black and Latino neighborhoods.

But amid all the stumbling by Giuliani and his staff and the gnashing of liberal teeth by progressives, several delicate political, social and moral questions finally received the attention they deserved:

What is society’s responsibility to its most vulnerable citizens? Should government just label such people as “homeless” and allow them to rot in cardboard boxes on the sidewalk? Or should government — and the vast umbrella of well-intentioned nonprofit groups who rake in tax dollars — take proactive measures?

Those questions have never really been fully answered.

Adams’ proposal this week is yet another effort to find answers.

As a starting point, Adams is targeting for immediate help to homeless people who suffer from untreated mental illnesses. Under Adams’ plan, such people would be forcibly removed from New York’s streets and involuntarily hospitalized or placed in other protective institutions.

It’s not entirely clear how many people New York might have to deal with. But last January the city reported that at least 3,400 people live on New York’s streets. That number is widely considered to be an undercount. What’s more, the Coalition for the Homeless advocacy group has long claimed that a large majority of unsheltered people suffer from mental illnesses or other severe health problems.

So while we may not have an accurate count of how many mentally ill homeless New York may have to care for, it’s not far-fetched to assume that the number may be in the thousands.

Which brings us to these questions:

Where do we put such people?

And who decides whether they are mentally ill?

Sadly, this problem — and these questions — were first raised a half-century ago. But the problem festered. And the questions lingered without real answers. Frustration rippled through New York’s neighborhoods and plenty of other communities, even in suburbia.

Which brings us to Rudy Giuliani. As part of his anti-crime effort in the early 1990s, he ordered the removal of homeless people from New York’s streets and parks.

He was cheered by many — understandably. People were fed up. But Giuliani never had a larger plan to actually help the chronic homeless find long-term peace and security. Giuliani offered a short-term solution. And, in the short term, it worked.

Adams now faces the same challenge. His proposal this week may offer a quick solution to homelessness. It may also put an end to the some of the crimes by the homeless in New York’s subways. But what about the deeper problem of people who can’t find shelter?

One of the great failures of the past half-century is how politicians of all political stripes refused to really tackle America’s burgeoning homelessness problem — and the resultant crime and drug abuse that it fomented especially in many poor sections of cities.

More:This NJ man is pushing a shopping cart across America to help homeless veterans

More:'It's a willingness issue': This is why some Paterson homeless won't seek shelter

More:After 40 years, Toni's Kitchen keeps looking to the future to help Montclair community

The problem began amid the allegedly good intentions of post-1960s liberalism to close down state-run hospitals and other government institutions that warehoused the mentally ill.

Many of these places were crucibles of pain. Think Nurse Ratched in “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” and you’ll get the idea. In far too many cases, our nation’s mentally ill were essentially tortured. So it’s completely understandable that the state mental hospitals and other institutions that perpetuated this sad state of affairs were shuttered.

But government never took the next step and found a better place for the mentally ill to live. Instead, far too many states embraced the idea that mentally ill people could live “independently” and receive treatment in community-based mental health centers.

For some, the plan worked well. But for the most severely ill mental patients, independent living became a cardboard box on a sidewalk and a day spent panhandling.

The failures by government didn’t stop there, however. Instead of correcting this problem, most politicians ignored it. Skin-flint Republicans, intoxicated with Reagan-era notions during the 1980s of cutting government spending to the bare bones, refused to fund a new system of care for the mentally ill. But Republicans should not bear the full blame here. Far too many progressives embraced the silly logic of so-called “homeless advocates” who championed the misguided idea that people should be allowed to “live on the streets” or in parks if they could not find shelter elsewhere.

Sometimes religious institutions pitched in with solutions. Volunteers cooked meals. Churches turned over their sanctuaries so the homeless could find a warm spot on frigid winter nights.

But homeless people who suffered from severe mental illnesses were the most difficult to help. Many had drug or alcohol addictions. And many also had chronic physical problems and other health issues that worsened during their years — sometimes decades — of living on the street.

“I want to talk to you about a crisis we see all around us: People with severe and untreated mental illness who live out in the open, on the streets, in our subways, in danger and in need,” Adams said this week in announcing his plan.

“We see them every day,” he went on. “And our city workers are familiar with their stories. The man standing all day on the street across from the building he was evicted from 25 years ago, waiting to be let in. The shadow-boxer on the street corner in Midtown, mumbling to himself as he jabs at an invisible adversary. The unresponsive man unable to get off the train at the end of the line without assistance from our mobile crisis team.”

We all know these people. You don’t need to walk the streets of New York City to find them. The homeless are seeking shelter under highway overpasses across Northern New Jersey. Or in bus stations, from Newark to Hackensack. Or in dugouts at Little League baseball fields across suburbia.

To name just a few spots.

Adams is trying to shine a spotlight on this problem. But his plan still has major shortcomings.

He promises, for example, that “mobile crisis teams” that include police and social workers will be formed to remove the mentally ill from the streets. But training for such teams is still not in place.

And once the homeless are taken off the streets, it’s still unclear where Adams plans to put them. Hospitals are already overcrowded. And perhaps a hospital bed is not the best place for the homeless anyway.

The mayor managed to set up a tent city for undocumented migrants who were bused to New York City from Texas. Why not a tent city for the homeless U.S. citizens with mental problems as a temporary place to find solace and perhaps a new path of life?

This is just a hint of the larger political and social conundrum for Adams. To his credit, at least he is speaking about this problem rather than just wringing his hands or ignoring it like far too many Democrats and Republicans before him.

But this journey is just beginning.

Mike Kelly is an award-winning columnist for NorthJersey.com as well as the author of three critically acclaimed non-fiction books and a podcast and documentary film producer. To get unlimited access to his insightful thoughts on how we live life in New Jersey, please subscribe or activate your digital account today.

Email: kellym@northjersey.com

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: NY takes step to solve homelessness. Is this a blueprint?