Oak Ridge League members moved by Alabama civil rights tour

Carolyn Krause brings us a two-part series. This first one takes us on a recent tour by the League of Women Voters of Oak Ridge to see civil rights locations in Alabama. I believe Oak Ridge is soon to become prominent on the nation’s civil rights tour with the national recognition of the Scarboro 85 and their leadership by being the first to desegregate public schools in the Southeast in September 1955. Enjoy the tour with the LWVOR group.

***

Last Sept. 6-9, 35 members of the League of Women Voters of Oak Ridge and their guests traveled to and from Alabama, where they toured civil rights sites in Tuskegee, Montgomery and Birmingham. Their last day was almost a week before the 60th anniversary of the Sept. 15, 1963, bombing of the 16th Avenue Baptist Church, which killed four young Black girls right before the Sunday worship service was to start.

In a presentation on Zoom to the Women Interfaith Dialogue of Oak Ridge (WIDOR) group, LWVOR members who made the trip talked about their emotional reactions to the brutal injustices inflicted on Black Americans by white Americans and to the inspirational, peaceful responses of the Black protestors fighting for their rights.

Carolyn Dipboye, president of LWVOR, which organized the civil rights tour, told the WIDOR audience, “We witnessed massive injustice, but we also witnessed great acts of courage and determination. Because of those acts of courage and determination, our nation was able to make some significant changes although those are not the only changes that are needed. It is hoped that those of us who made the tour will be inspired to help finish the work of bringing civil rights to all Americans.”

Many of the LWVOR trip participants, most of whom are white, talked about experiencing intense emotions from what they saw and learned on the trip. Asked by The Oak Ridger if the group experienced a mix of sadness, shock, anger, guilt and despair over the cruelty perpetrated by white people on Black groups mainly because they were perceived as different, Dipboye said yes. She added that the participants also admired, and were inspired by, the bravery of the wrongfully oppressed people, some of whom took the risk of joining peaceful protests.

She told WIDOR that American youth should be encouraged to visit these sites to learn about an important aspect of American history.

“It’s too dangerous for Americans to forget our history,” she said.

Dipboye provided the itinerary: “We made our first stop at the Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site. We spent the following day-and-a-half in Montgomery, where we toured the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration, with its outdoor Lynching Museum. We also visited the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Civil Rights Memorial Center with its dramatic outside memorial designed by Maya Lin. We were particularly moved by the center’s Martyr Room and the Apathy Is Not an Option Orientation Theater.

“On the final day, we visited the National Civil Rights National Area in Birmingham, which some people called Bombingham. We were moved by an in-depth tour of the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, which presented original media coverage of the protests that took place there.

“We saw the outside of the 16th Street Baptist Church, where many of us still remember the bombing 60 years ago on a Sunday that took the lives of four little girls.”

Carol Plasil recalled that when she was a teenager and her family took a trip from New York City to Florida, they were on a ferry boat where she saw “Colored” and “White” drinking fountains. At first, she thought that “colored” meant the water was bubblegum flavored. Then, she said, “it struck me like a bolt of lightning that I had vaguely heard about how Black and white people were supposed to get their water from different fountains.”

Margo Spore showed a photo of a Black woman sitting at a table taking a difficult-to-pass literacy test to determine whether she was eligible to vote while a white official stood by.

Larry Dipboye, who like his wife Carolyn is an ordained minister, was impressed by the peaceful solemnity and reverence shown by visitors to the civil rights museums. He had previously taught courses on American slavery and racism for the Oak Ridge Institute for Continued Learning.

He said he was not aware of racism while growing up in Houston until the Brown versus Board of Education decision by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1954 when he heard white students saying, “We’re going to have to go to school with Blacks.”

At the Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site, he said, “you learn how bad things were for the Black pilots who fought during World War II and then came home to find out they were not appreciated, but rather were again treated as fourth-class citizens, below the level of humanity.”

He remarked that the most dangerous jobs in the steel industry, in which his father worked as an operator in a rolling mill in Houston, were carried out by slave labor up to the end of the Civil War, assigned to Black prisoners after the war and assigned to Black employees until the 1960s.

“Many large corporations made their profits off the slave labor taken from the prisons, including the steel companies in Birmingham and coal mines in the South,” he added. While he was in Texas, he learned that enslaved or imprisoned Black people “were worked to death in the sugar cane industry in South America and Cuba.”

Later, he noted that Southern states got away with making slaves of Black convicts because of the “involuntary servitude” loophole in the Thirteenth Amendment, which outlawed slavery except as punishment for crimes.

He implied that “latter-day slavery” may still exist today in the form of mass incarceration of people of color. In 2021, people of color constituted more than two-thirds (69%) of the U.S. prison population, mainly for violent and often minor drug offenses.

Speaking of the Lynching Museum, Larry Dipboye noted that he was struck by the number of hanging rectangular boxes that each represented a county where numerous lynchings (hangings of mostly Black Americans) took place. Plasil said the Oak Ridge visitors saw evidence that lynchings had occurred in Tennessee's Morgan and Roane counties, but not in Anderson County.

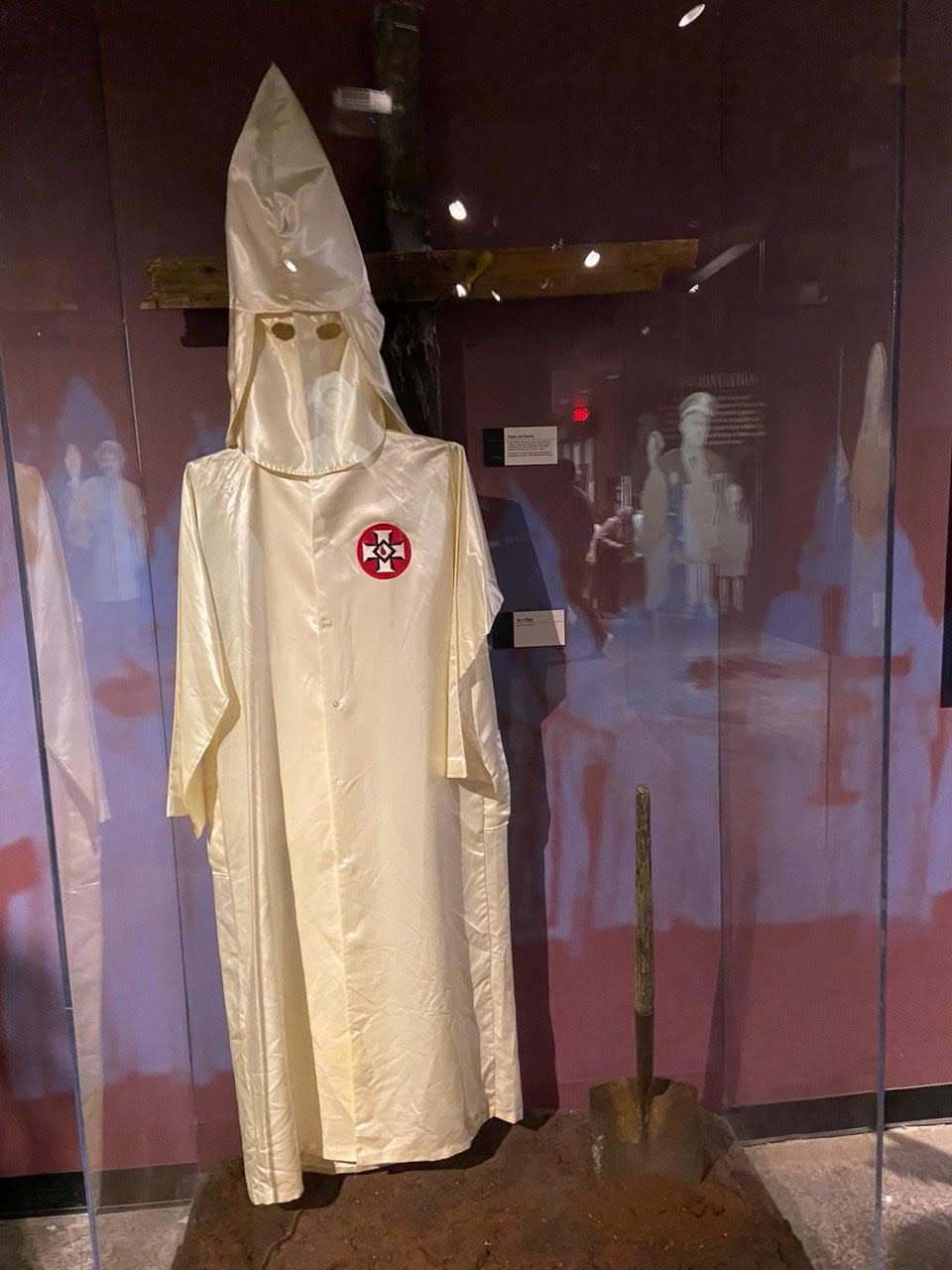

One document reported that more than 4,440 racial terror lynchings took place in the United States between 1877 and 1950. The Ku Klux Klan, an American white supremacist terrorist hate group, lynched many Black Americans, who they believed were inferior humans. Dipboye said it is stunning “how many people died violently because they happened to have the wrong color of skin in this country.”

Spore said she was shocked to learn that half of the families of enslaved Blacks “were ripped apart” by plantation owners.

Plasil was impressed by a map with dots showing more than 30,000 voyages by slave ships that sailed from West Africa to North and South America, including the Caribbean islands, between 1514 and 1866. She added that all the museums were “well done” and that the Birmingham Civil Rights Museum showed the contributions of Black people to American society.

Frank Plasil, who grew up in Europe, said that he “had no idea” that these injustices toward Black people had occurred in the United States.

“It was kind of an awakening somehow and a very emotional experience that will stay with me forever,” he said.

Larry Dipboye said that all the museums the group visited had a search-and-scan process, which is why he had to leave his pocketknife with the guard at the entrance of one site.

“I suspect that all these places are under a real threat because some people in power want Americans to forget history that is uncomfortable," he said. "If you forget history, you are apt to repeat it. We need these civil rights sites to remind us where we’ve been.”

***

Thank you Carolyn, for a well informed tour that brought to our attention many of the details of the civil rights movement in Alabama. Next the second in this series focuses on another LWVOR event where voting rights was discussed.

D. Ray Smith is the city of Oak Ridge historian. His "Historically Speaking" columns are published each week in The Oak Ridger.

This article originally appeared on Oakridger: Oak Ridge League members moved by Alabama civil rights tour