In occupied Ukraine, the best way to survive is to stay silent

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

After five of her elderly neighbours died because they could not access medical care, Laryssa knew it was time to get Russian citizenship.

She felt nothing but anger towards Moscow and President Vladimir Putin, whose occupying forces have ruled her home city of Melitopol with an iron fist for almost two years.

Yet without Russian citizenship, Laryssa, 68, could not see a doctor, and soon she would even lose her social benefits.

There were other dangers too – passing a Russian checkpoint with a Ukrainian passport could lead to interrogation and phone searches. Two of her friends had disappeared after being accused of supporting Ukraine.

“The best way to survive is to stay silent. Don’t say one word more than you need,” Laryssa said. “You don’t know who will use this information.”

Now the operational capital of occupied Zaporizhzhia, Melitopol had been home to just over 150,000 Ukrainians before the war. Most of them have now left and more than 100,000 Russians have moved in.

Once a vibrant city, today the streets are dirty and its buildings – neglected by the Russian-installed authorities – are in disrepair.

Russian flags have been raised across the city, while symbols of Ukrainian identity have been erased – letters crudely hacked away from signs to suit the language of the occupiers. A statue of Lenin was reinstalled, seven years after it was torn down in the wake of the country’s pro-Europe revolution.

Applying for the passport was humiliating enough – forcing people to change their citizenship is a violation of international law – but when it arrived Laryssa was also forced to take an oath of loyalty to Russia, promising to observe the rights and freedoms of its citizens.

“I was so angry, they don’t allow you any self-respect,” the 68-year-old told The Telegraph over the phone. “I couldn’t restrain myself and asked them: ‘Do you want me to sing the national anthem as well?’”

Efforts to enforce the uptake of citizenship have been ramped up ahead of next month’s sham presidential election. A win for Putin is a foregone conclusion, but the illusion of democracy is still important.

Billboards emblazoned with the president’s face loom over Ukraine’s occupied cities, carrying slogans like “a strong president, is a strong Russia!”. Troops, officials and local collaborators have already started paying home visits, urging people to take part.

“They told us they will check lists and it will be dangerous for those who don’t vote,” Laryssa said.

Two years after Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and a decade into the conflict in the east, a fifth of the country remains occupied. Soldiers and ammunition are in short supply, and with Western support waning, hopes for full liberation and a swift victory have faded.

“We remember history: the Baltics and eastern Germany suffered 50 years of occupation. We are preparing ourselves that, at our age, we may not see family in Ukraine again,” she said.

Few journalists are able to access the occupied territories, where the sharing of information and communications are heavily controlled by the occupiers. However, The Telegraph spoke to five officials, as well as more than a dozen people who are either living in occupied territory or had escaped to Ukraine that day, to show the reality of life under occupation. The surnames of all the civilians interviewed have been concealed to prevent repercussions against them or their relatives living in occupied areas.

In the regions occupied since 2014, Crimea and the so-called republics of Luhansk and Donetsk, life is tough, but the system is well established. For the regions that fell to Russia after 2022, things are more uncertain and fraught. People are living in dire conditions under the most repressive Russian rule.

Those who can, flee, making daring escapes into enemy territory and on to Europe, or into Ukraine. Those who can’t are often sick, elderly or poverty-stricken, or too concerned for vulnerable family members to leave.

Russian civilians and military have relocated to the territories in droves, lured by the promise of high wages and other privileges. In some cities there are more Russians than Ukrainians. Locals say they have become an underclass, restricted to low-paid work and robbed of human rights such as freedom of speech or movement.

Russification

Ukrainians enjoy so little freedom that even routine activities such as a walk to the shop carry the potential for interrogation. As a result, most lead reclusive lives and even growing their own food where possible. Detentions and disappearances are common.

“The Russians don’t respect us and they don’t take care of us,” said Laryssa.

The strict control extends into the living room – TVs show only Russian channels, and news is heavily laden with propaganda about the state’s “special military operation”. Those who still have internet access use a VPN to watch Ukrainian shows, but they are to be blocked from March 1.

Permission to travel is also tightly controlled, with permits required to leave a town or city. Ukrainian phone Sims are prohibited, forcing people onto Russian networks or to hide them at home. Food is expensive and of poor quality, imported from Russia or Iran. Ukrainian bank cards don’t work and the hryvnia is banned. Illegal brokers offer currency transfers – but it comes with a risk of arrest for those who use it.

The new administrations have done little to repair damaged infrastructure and rarely carry out maintenance. In some regions, people spend weeks or months at a time without internet or electricity – and they have no central heating, in a country where winter temperatures can plummet to -20C.

Destruction

According to Iryna Vereshchuk, deputy prime minister and minister for reintegration of the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine, the scale of destruction in occupied areas is “massive”, while Russia continues to ignore international law.

“At least 16,000 civilians are being kept in prisons, camps or torture rooms. Under human rights laws, they must be returned to Ukraine,” she said.

Meanwhile, children continue to be deported from occupied regions. Kyiv estimates more than 19,500 minors have been taken to Russia, where they have no jurisdiction and can do little to either protect or return them.

“There are around 4,000 orphans in occupied territory and we are worried they will be deported,” said Ms Vereshchuk. “Russia changes the children’s names and their date of birth so they’re hard to find … it is a genocide against our population.”

Torture chambers have been located by Ukrainian authorities across the territories, including ones in Mariupol and Kherson and at least five in Melitopol. They are often in police station basements or buildings used by the Federal Security Service.

“I think occupied territories are one big prison and one big war crime,” said Ivan Fedorov, the mayor of Melitopol and head of Zaporizhzhia Oblast Military Administration.

In occupied Kherson, five per cent of residents have been detained since the war began, according to Oleksandr Tolokonnikov, spokesman for Kherson Regional State Administration.

In a shocking instance from last December, a teenage boy from a village in the Kakhovka district was seized by Russian forces after taking a photo near a checkpoint. They took him home and shot him dead in front of his distraught mother.

One man, Oleksandr from Tokmak, Zaporizhzhia, said he had been beaten by Russian forces, who also stole farming machinery from his property, while several others said they had witnessed it happening to others.

Mariupol

Of all the occupied territories, Mariupol has seen the worst of Russian aggression. More than half of the city was destroyed by Russia during a brutal siege in 2020 that killed at least 10,000 people, according to a report by Ukrainian NGO Truth Hounds and Human Rights Watch. It remains the biggest atrocity of the war so far.

The population has shrunk from just over half a million pre-war to around 150,000. Almost half of the residents are now Russian, with an additional 25,000 to 45,000 expected to relocate to the city by next year, according to Petro Andryushchenko, adviser to the city’s mayor. The Ukrainians who remain continue to suffer.

Roughly 30 per cent of residents have no heating and many are living in damaged or dangerous housing, leaving them vulnerable to injury and sickness. Colds and flu are rife and the problem is compounded by a lack of access to healthcare.

“The death rate is at its highest since the siege ended, with 400 people dying a week – even teenagers – of treatable illnesses,” Mr Andryushchenko said.

Almost everyone has now, like Laryssa, taken Russian citizenship. It will be mandatory from June 1, with Russia threatening to label those who don’t have it as foreigners.

Penalties include intimidation, detention and restrictions on basic necessities such as medical care, pension payments and even water.

Ukraine says those who take a passport as a means of survival will not be penalised legally, but men of fighting age risk being drafted into Russia’s forces. Mr Andryushchenko said he knows of at least 20 men from the city who have been sent to fight against their own country, while 55 have been called up for military service.

Thousands from across the occupied territories are already working to build fortifications along the front line; often they are older men who had worked in coal mines or manufacturing.

“They are caught off the street and used by the army to dig trenches or serve in a ‘meat battalion’, where they’re sent to the south just to die,” said Artem Lysohor, head of the Luhansk Oblast State Administration.

Resistance

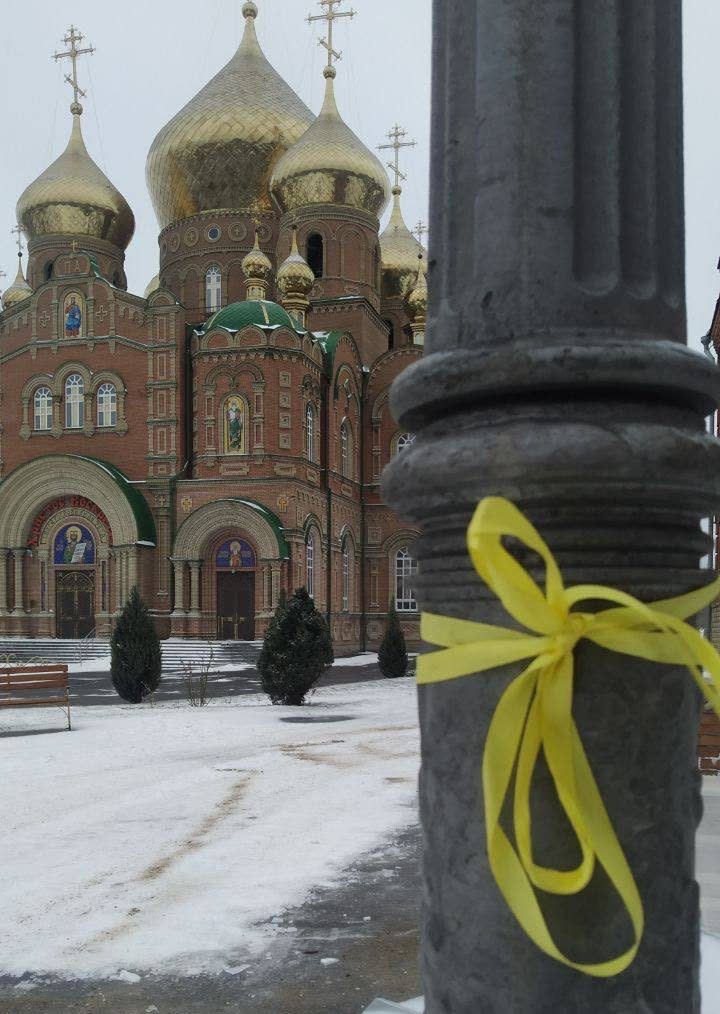

The picture is bleak, but a pro-Ukrainian spirit still holds. According to Kateryna, who is under 35 and part of non-violent resistance movement Yellow Ribbon, there are still people in Luhansk and Donetsk who, even after 10 years of occupation, continue to hide Ukrainian flags to fly after liberation.

Kostyantun, in Donetsk, said that although he has no relatives in Ukraine, with his father living locally and his mother in Krasnodar, Russia, the family and their neighbours all still support Kyiv and “the dream of de-occupation”.

He said: “If I compare life before 2014 with now, I can say that it is worth living in Ukraine. Russia did not bring anything good.”

Yellow Ribbon has two roles, Kateryna says. The first is to show local people that “Ukraine is still here”. This is done partly through guerrilla street art – its members risk detention to tie yellow ribbons around occupied towns and cities or graffiti pro-Ukrainian symbols in public areas.

The group is also actively involved in channelling information to both the public and Ukrainian forces. It has about 10,000 members, with more joining in activities after seeing the symbols around town, without realising they’re part of an organised movement. They make Ukrainian flags, with members distributing them through anonymous dead drops.

In Mariupol, a separate resistance group is said to be behind the deaths of at least 50 Russian soldiers, some killed with poison. They are believed to have helped take down Russian aircraft and pass on information about important military positions to the Ukrainian army.

Kateryna is part of the resistance in occupied Kherson. No one, including her family, know about her work, which could lead to her being detained, or worse.

Yet she is not afraid of getting caught, she says over the phone from Crimea, where she has moved temporarily to avoid being forced to vote for President Putin – if she is not at home, it is hard for the administration to pressure her. The only thing that scares her is the prospect of long-term occupation.

“My biggest fear is to be forgotten,” she said.

Escape

There is only one route to escape the occupied regions and cross into Ukrainian-held territory and it is expensive and physically exhausting. A bus to Russia’s Belgorod region, with tickets costing up to $500 (£400) each, and then a cold and terrifying 1.2-mile walk across the border amid nearby shelling.

The route is strewn with abandoned luggage, discarded by those unable to carry the few positions they brought with them the distance, and scattered with fragments of Russian roubles, torn up in defiance.

As many as 120 people a day make it to Ukraine, with more making the journey in the warmer summer months. One of them is Olha, 67, who has diabetes. The four-day journey sent her blood pressure soaring and by the time she arrived at a shelter in Sumy, in Ukraine’s north-east, last week, she was vomiting into a bag.

The grandmother, who wears purple-tinted glasses perched on her nose, has a problem with her foot. It is a consequence of a lack of access to the diabetes care she needs, with medicine scarce in occupied regions and access to doctors even scarcer.

As well as being denied medical care without citizenship, most of the hospitals are reserved for the military because of staff and supply shortages. Olha said she had to drive two hours from her house in Polohy to Berdyansk, both in the Zaporizhzhia region, to find a hospital that would see her about her foot.

“They offered me two treatment options,” she says. “Either we amputate it, or you go to Ukraine to get help.”

New arrivals spend their first night of freedom in almost two years at the Sumy shelter, with Ukrainian flags hanging from the ceiling. A huge map of the country is tacked to the wall – it makes no reference to Russia’s annexation of territory.

“Can I go out for a smoke?” one woman asked a volunteer. “You can do whatever you want, you’re in a free country now,” he replied.

At the shelter, arrivals stay for one night, receiving food, cash, and medical and mental health support, before catching trains to other parts of Ukraine. It has become a dumping ground for unwanted Russian money, with some arrivals defacing 10,000 rouble notes, worth £85 – equivalent to a month’s pension. They have a quarantine box for Russian food – the Museum of Stomach Dysfunction, shelter manager Kateryna Arisoy calls it.

Ganna, 37, who is also from Polohy, arrived with a caramel-coloured pet rat nestled against her neck. Originally from Donetsk, she has suffered occupation once before, fleeing after a year in 2015.

Ganna stayed in Polohy to wait for liberation, but when the front line stopped moving, she decided to stop waiting and start doing something. “I want to be drafted into the Ukrainian forces,” she says.

Andriy, 22, and his mother, Natalya, 47, have weathered some of the worst of Russian behaviour in occupied Kherson, including huge floods last year after the blowing up of the region’s Nova Khakova dam. They saw people beaten in the street for expressing anti-Russian sentiment, and children from their community have been taken to Russia.

The build-up to March’s presidential election forced them to leave, but the push to take a passport in order to vote has been ramped up with further restrictions for those who don’t.

“Life became impossible without it,” Andriy said. The only work available was in agricultural fields, which Natalya took, while Andriy stayed at home to avoid Russian checkpoints.

Despite leaving, they still believe the left bank of Kherson will be liberated, just as the right bank was in 2022, and that it will resist to the end.

As they arrived in Belgorod to walk across the border, Andriy noticed mines on the ground nearby. The path to Ukraine was strewn with discarded roubles, and Andriy threw his last 50 down, too.