The ocean keeps gulping up a colossal amount of CO2 from the air, but will it last?

The ocean has proved to be an exceptionally selfless and dependable planetary companion.

With no benefit to itself, Earth's vast sea has gulped up around 30 percent of the carbon dioxide humans emitted into Earth's atmosphere over the last century. Critically, scientists have now confirmed that the ocean in recent decades has continued its steadfast rate of CO2 absorption, rather than letting the potent greenhouse gas further saturate the skies.

Their research, published Thursday in the journal Science, found that between 1994 and 2007, the oceans reliably sucked up about 31 percent of the carbon dioxide produced by humans, even as CO2 concentrations skyrocketed to their highest levels in at least 800,000 years. This means the ocean is now absorbing a significantly larger bulk of carbon, amounting to well over 2 trillion tons each year.

"We can regard what the ocean is doing for us as providing a service, by mitigating CO2 in the atmosphere," said Matthew Long, an oceanographer at the National Center for Atmospheric Research who had no role in the study.

But a weighty question still looms: How much longer can we rely on the ocean to so effectively store away carbon dioxide, and stave off considerably more global warming?

"At some point the ability of the ocean to absorb carbon will start to diminish," said Jeremy Mathis, a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) climate scientist who coauthored the study. "It means atmospheric CO2 levels could go up faster than they already are."

"That's a big deal," Mathis emphasized.

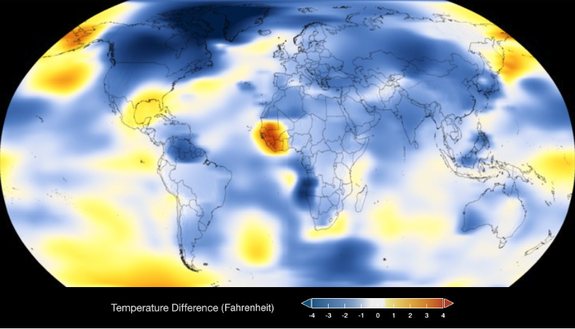

Image: noaa

It's a big deal because carbon dioxide levels aren't just abnormally high, but today's accelerated pace of heat and carbon dioxide rise is nearly unparalleled on Earth. "What’s important to recognize is the changes humanity is driving at present are commensurate with the most significant events in the history of life on this planet," said Long. That means — as long as we continue emitting profound amounts of heat-trapping gases — we'll need the ocean to keep absorbing massive quantities of CO2, so the planet doesn't grow absurdly hot.

Fortunately, there's still time. For the next 50 years or so, the oceans will continue to gulp up about the same amount of carbon dioxide.

"[The ocean's] going to continue to help suck up CO2," said Josh Willis, an oceanographer at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory who had no role in the research. "It's like it's eating at a really big buffet, really slowly," he explained. "It’ll keep going to the buffet for a long time."

That's good news for us, a species whose carbon emissions likely won't even peak for another decade.

But it's terrible news for the ocean.

SEE ALSO: The Green New Deal: Historians weigh in on the immense scale required to pull it off

"The ocean will keep cleaning up some of our mess, but it does that at a price to itself," said Willis.

As they say, nice guys finish last.

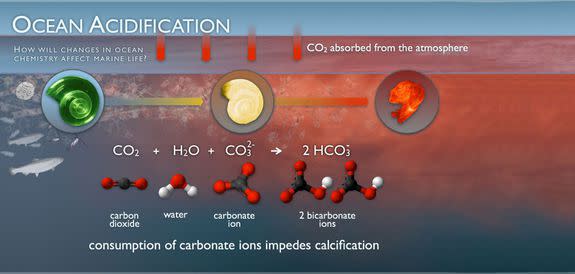

The ocean grows more acidic as it sucks up CO2. "Every additional bit of CO2 the ocean takes up protects us from the worst of climate change but does damage to plants and animals in the ocean," said Curtis Deutsch, a chemical oceanographer at the University of Washington, who also had no involvement in the study.

Just how much damage? That's a hot area of research. Increasingly acidic waters are expected to dissolve the skeletons of big swaths of coral, for instance. But it's not just acidified waters that critters must worry about. The oceans also absorb about 93 percent of human-created heat on Earth, which boosts the odds of deadly marine heat waves — the type that killed 30 percent of corals in the Great Barrier Reef over just nine months. What's more, warmer waters have resulted in the loss of oxygen in the seas, which much sea life needs to survive. That's a triple-whammy of potent environmental threats. "We expect this to have substantial impacts on marine ecosystems," said Long.

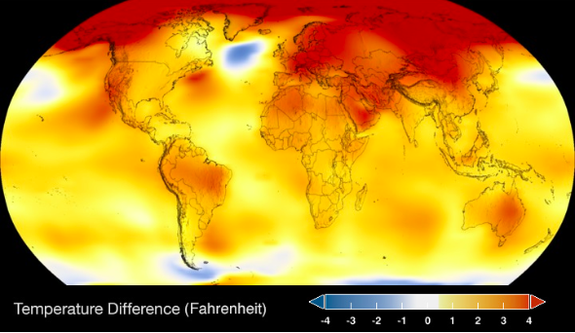

Image: noaa

During the second half of this century, though, the story will change. Marine researchers still expect the oceans to gulp up considerable loads of carbon dioxide, but this ability may gradually start to diminish, noted Long. That's because ocean circulation — in which deeper, colder waters rise to the surface and replace warmer ocean waters — will be reduced. In short, water near the surface will have absorbed the most heat (as the world warms) and create a layer of buoyant sea. This makes it increasingly difficult for fresh waters from the deep — which aren't yet oversaturated with carbon — to circulate to the surface and absorb lots more CO2 from the air, Long explained.

These changes, along with ocean acidification, won't be easily reversed. "We’re essentially baking in changes that will be very long-lived," said Long.

But scientists don't expect any extreme or catastrophic disruptions to the ocean's carbon uptake anytime in the next century, at least. "The ocean would basically have to stop circulating," said Deutsch. "And that's just not feasible."

Image: nasa

Image: nasa

Still, marine scientists emphasize that we must continue monitoring the oceans to ensure the ocean is as dependable as we think it is, and critically, to watch for any unexpected changes amid Earth's rapidly changing climate. This is no simple task. Collecting this ocean data often involves six to eight-week-long research missions across vast lengths of sea (like Alaska to Hawaii), wherein scientists collect water samples every 10 miles. "It's timely and fairly expensive," said Mathis. "But we have to continue to invest in the science that allows us to go out and do these surveys."

"Otherwise we’re just flying blind — we just don't understand," added Long.

Although the oceans have undoubtedly quelled a significant amount of warming over the last century, they can't ever be humanity's total climate savior. There will just be too much carbon dioxide saturating the air, too much for the seas to handle. The ocean won't stave off radical climate disruption, deadly heat waves, and ruinous damage to crops. In other words, it wouldn't be good if we ever reach a point where the climate has overloaded the oceans with CO2 and heat. But we would already be in big trouble.

"So it could get worse," said Long. "But it will already be pretty bad."

WATCH: Ever wonder how the universe might end?