How Office Life And 'The End Of Work' Became The Biggest Book Trend Of 2019

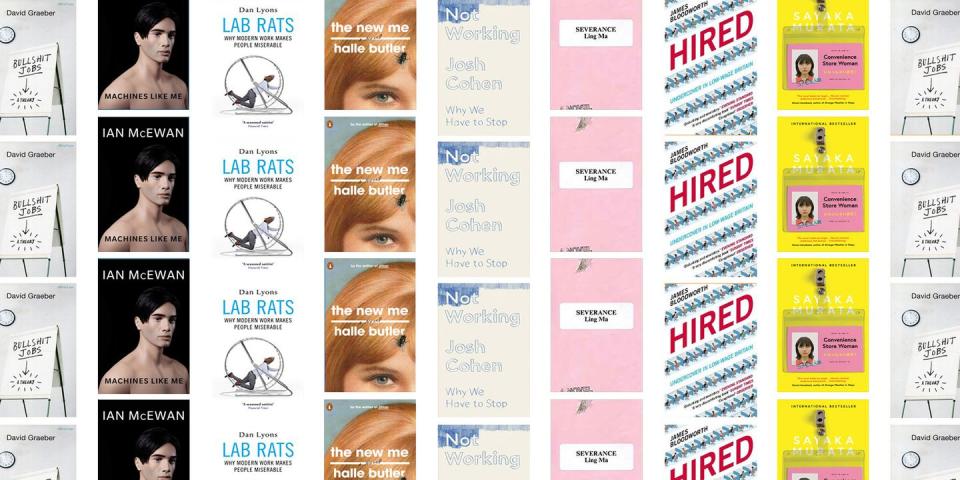

In Ian McEwan's new novel Machines Like Me, the rise of Artificial Intelligence has swallowed jobs on shop floors, in accounting, hospitals, marketing, logistics and human resources. This rise of robotisation forces the protagonist Charlie to muses: "Soon enough, most of us would have to think again what our lives were for. Not work. Fishing? Wrestling? Learning Latin?"

Charlie's robot takes over his dwindling career gaming the stock markets, an agreement that initially offers the carefree joy of shirking work while still earning money but soon becomes an albatross around his neck. "My debts were settled. I'd paid a cash deposit on a glamorous urban pile. I was in love. How could I complain? But I did. I felt useless."

McEwan's reckoning about the machines coming for our jobs (and partners) comes in the midst of a trend this year for both fiction and non-fiction titles that examine the future of the traditional 9-5.

In Lab Rats: Why Modern Work Makes People Miserable, Dan Lyons rallies against the excruciating trappings of modern offices, from team building exercises to hot-desking. "We offer no job security. This is not a career. You are serving a short-term tour of duty," he writes.

Elsewhere, he suggests modern work expects humans to become more like the machines that are replacing them: "Once upon a time we used technology, but today technology uses us. We're hired by machines, managed by them, even fired by them."

Josh Cohen's Not Working: Why We Have to Stop goes a step further, not confining his critique to the Silicon Valley model of 'culture building' but the very notion of work itself. "My contention is that not working is at least at as fundamental as working to who and what we are," he writes, suggesting that we have wrongly been conditioned to associate not being productive with shame and laziness.

Instead he advocates a kind of stillness and inertia in place of productivity and accomplishment. A romantic theory, but the exemplars of slothfulness he offers are Garfield and Homer Simpson - as opposed to Emily Dickinson and Orson Welles - it doesn't feel much of a blueprint for real life.

Last year anthropologist and writer David Graeber published Bullshit Jobs, which also considers the world of modern work some kind of underhand trick. Graeber questions how labour has become a 'state of being' rather than a genuinely productive enterprise, and asks: "If your job didn't exist, would anybody miss it?", while suggesting pointless jobs have been created with the goal of keeping us occupied. "How can one even begin to speak of dignity in labor [sic] when one secretly feels one's job should not exist?" he asks. A far cry from Stephen Hawking's assertion that "Work gives you meaning and purpose".

There's also been numerous examinations of the gig economy which is flourishing at a time of job insecurity and income inequality and largely behind the government's deceptively impressive employment rates. One book was James Bloodworth's Hired: Six Months Undercover in Low-Wage Britain from last year. In it he documents how "work for many people has gone from being a source of pride to a relentless and dehumanising assault on their dignity." Bloodworth also examines the psychological tricks companies play on employees to cover up ethically dubious practises, like Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos calling every employee an 'associate', which Bloodworth claims is "a ruse designed to foster the illusion you were all one big happy family."

The job that wants to be your best friend is nothing new. But these tricks go beyond the Facebook snacks fridges and Google beanbags to a kind of psychological bribery used to pressure employees into feeling indebted to a company. In a recent New Yorker piece about athleisure brand (though don't call them that) Outdoor Voices, the company VP makes the startling claim that - thanks to a work culture typified by 'surprise birthday luaus' and cork-boards filled with photos of employees’ dogs - "all of the employees seem as if they would be willing to work there even if they were not being paid."

Should anyone be so grateful for meaningful work they would continue if they weren't being compensated? It's a statement that makes them sound more like brainwashed drones than well-rounded employees. While Graeber questioned whether dignity in labour can exist in a pointless job, working in a meaningful or cool job can come with a different kind of indignity - that of feeling inappropriately indebted to a company.

There is a sense in fiction, too, that modern work has become synonymous with horror and the office has become the new setting for novels tinged with dystopia and horror. One of the standout books of 2018 was Ling Ma's Severance, set in a New York crumbling after an outbreak of Shen Fever. One of the most chilling aspects of the book is how its protagonist continues the monotonous routine of daily work even as the city empties of all signs of life, as though the act of working is robotically coded within her.

A hotly anticipated book this year is Halle Butler's The New Me which, like the best-selling Convenience Store Woman, revolves around a female character working a menial job many would see as temporary impasse. Both novels challenge the notion that everyone strives for professional success and an upward career trajectory. Instead, flatlining is portrayed as fulfilling.

At a time when our concept of what work means and should look is in flux, it's not hard to see why this trend is emerging. The notion of the 9 to 5 is being challenged by successful trials for a four day working week in countries such as Sweden and New Zealand, suggesting working less hours both boosts morale and productivity. Meanwhile the rise of robotisation and Artificial Intelligence means the need to consider a Universal Basic Income to stabilise wealth inequality has become more pressing.

In both Cohen and Lyons' recently published works, what they seem to be questioning is whether modern work is compatible with happiness. As many earnest op-ed will be all too happy to remind millennials, work isn't supposed to be about joy - but you still have to do it. The idea that work should be a pleasure has always been the preserve of the very wealthy, those with the financial security to pursue a more meaningful existence.

For many people the pressure to work longer and be contactable all hours of the day is increasing, while the rewards are not. Combine that reality with our increasing life spans, it's not surprising that the desire to do something more inspirational than transactional has begun to disrupt the hamster wheel. Presented together, these books paint a compelling case for rethinking modern work. The question, really, is what the alternative is.

('You Might Also Like',)