Officer was first on scene of one of the worst traffic accidents in US history

|

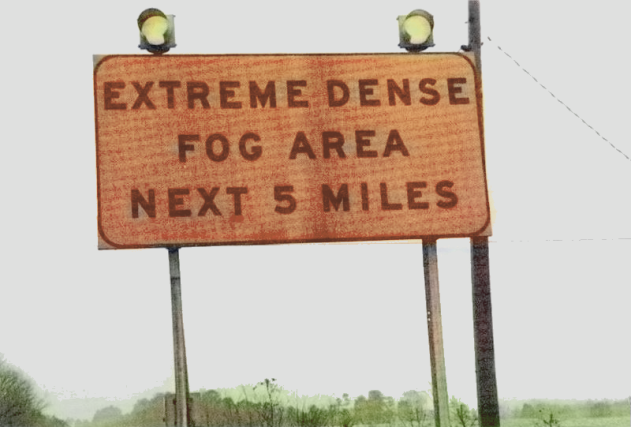

An extreme dense fog warning sign on I-75 in Tennessee in 1990. (NTSB) |

On the morning of Dec. 11, 1990, Bill Dyer's day began with a routine assignment: He was told to patrol the north end of Bradley County, Tennessee, for the county sheriff's office.

It was a beautiful morning as his shift began shortly before 9 a.m. The sun was shining brightly amid a clear blue sky. All seemed calm and fairly routine.

Yet, as he ventured farther north toward the Hiwassee River, fog came creeping in, and that splendid sunny day in southeastern Tennessee suddenly had vanished. As he continued to drive north, the fog worsened and became so dense he couldn't even see beyond the hood of the patrol vehicle.

"[The fog] got worse and worse the closer you got to the river," Dyer said in a phone interview with AccuWeather.

During his patrol, Dyer received a call to investigate a report of a wreck on Interstate 75 near the town of Calhoun, about 70 miles southwest of Knoxville. Navigating through the fog, which was producing near-zero visibility, was challenging, so he drove slowly. A low-lying area near the river, this stretch of I-75 had been prone to fog-related accidents since it opened in the early 1970s. It wasn't the first time Dyer had been called to investigate a crash in that stretch of highway, but this would be his first time responding amid foggy conditions.

|

Bill Dyer, 26 at the time, was the first law enforcement officer on the scene. (Photo/Bill Dyer) |

But when Dyer got to the river, which serves as the county line between Bradley County and neighboring McMinn County, there was no sign of any accident. He began to pull away and take the nearest exit to head back into Bradley County. As he ventured onto the exit on the northbound side of I-75, which was up a slight hill and toward an overpass that went back over the interstate, out of nowhere a badly-injured man stumbled out of the fog and right into his vehicle.

Dyer scrambled out of his car to assist the man, who was bleeding profusely and had skin peeling off his face.

"They're on fire, they're on fire," Dyer recalled the man saying.

Dyer, only 26 at the time, had no idea he was just called to the scene of one of the worst highway accidents in United States history.

After he encountered the badly-wounded man on the exit ramp, he realized a pileup collision was taking place below him on the interstate. But with the fog so thick, he could only hear the crash, rather than see it unfold, he recalled to AccuWeather. Over and over, he could hear the sounds of brakes screeching followed by numerous loud thuds as cars and trucks slammed into each other. Soon, he could hear numerous people screaming for help.

CLICK HERE FOR THE FREE ACCUWEATHER APP

Dyer was the first law enforcement officer on the crash site that day. He immediately notified dispatch that every available resource was needed to come to the scene immediately; he also radioed for the interstate to be shut down farther ahead.

It was unclear how long the crash had been ongoing when Dyer arrived, but he knew he couldn't let it continue. Once he was able to assist the wounded man to one of the first arriving ambulances, he headed back down toward the southbound lanes of the interstate and began trying to get the oncoming traffic to stop or at least to get as many cars as possible to slow down since drivers couldn't see him amid the fog.

He stood along the side of the road, waving his arms frantically on the southbound side of I-75, but many motorists simply didn't see him, and he said he was nearly run over more than once.

"I didn't know what else to do. I know I had to stop the cars, try to break the chain reaction because I could hear them crashing," he said, adding that he would later perform first aid on a number of victims.

|

This map shows the area where the crash occurred on Interstate 75 on Dec. 11, 1990. |

It wasn't until Dyer was walking right alongside the interstate that he slowly realized just how massive a pileup it had become.

All told, 99 vehicles were involved, and 12 people lost their lives. Another 42 suffered injuries. A temporary morgue was established as authorities and first responders spent the rest of the day identifying victims, some of whom had perished in burning vehicles, while also treating the wounded.

It took three days until that stretch of the highway could be used again, Dyer said. Construction crews needed to tear up the road and repave it since asphalt had melted due to the numerous cars and trucks that had been on fire. Dyer told AccuWeather that he can still recall how the stench of gasoline permeated the air amid the fog, which he said was so thick that day it resembled steam.

Archived footage of the crash from WTVC in Chattanooga, Tennessee, shows just how massive the crash site was when the fog lifted. Footage from the scene showed burnt-out vehicles that were smashed together in an astonishing stretch of twisted metal.

In 1992, the National Transportation Safety Board released an 85-page report on the crash. The probable cause was listed as "drivers responding to the sudden loss of visibility by operating their vehicles at significantly varying speeds."

The accident began around 9:10 a.m. and had occurred when a tractor-trailer traveling southbound had crashed into another tractor-trailer that had slowed due to the fog. Subsequently, another car careened into the second truck and was then hit by a third tractor-trailer. A fire ensued and engulfed two of the trucks and the car in flames. On the northbound side, one car crashed into the rear of another that had slowed down abruptly amid the fog. At that point, the massive chain reaction was underway, resulting in a total of 99 vehicles.

According to the NTSB report, fog warning beacons on signs that read "Extreme Dense Fog Area Next 5 Miles" had been activated by the Tennessee Highway Patrol for the southbound side of the interstate three days before the crash and had not been turned off. However, beacons had not been activated on the northbound side before or during the accident.

Roadways have become safer over the years due to technology, including that stretch of I-75. In 1993, the Tennessee Department of Transportation implemented a fog detection and warning system that has been upgraded over time and has made a significant difference in keeping motorists safe. Only one fog-related accident has been reported there, in 2001, since the implementation of the new system, according to the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA).

The system includes a fog detection area that covers a three-mile stretch of the interstate north and south of the Hiwassee River and an eight-mile warning zone in both directions leading up the fog-prone area. The components include nine forward-scatter visibility sensors, 14 microwave radar vehicle detectors and 21 closed caption television cameras.

Fog tends to form in river valleys in the late summer or fall as rivers are still relatively warm compared to the air just above, according to AccuWeather Senior Meteorologist John Feerick. "Combine that with the longer nights allowing for more cooling of the air above, there is some exchange of moisture between the warm water and the cooler air making the fog more likely to form in the river valleys," he explained.

Fog that typically forms in river valleys is known as radiational fog, according to AccuWeather Senior Meteorologist Alex Sosnowski. This kind of fog can form at any time of year when winds are light and air near the ground cools to the saturation point.

"It is common for radiational fog to form in low-lying areas or in the river valleys first and then to increase in size and reach higher elevations as the night progresses," Sosnowski stated. "The longer the night, the more extensive the radiational fog is likely to become. The lower the sun angle is during the day, the longer the fog is likely to linger after sunrise."

Temperature data cited in the NTSB report indicated that the weather was optimal for fog formation. The temperature around 5:30 a.m. that morning was 38 degrees Fahrenheit, and it would later drop to the mid-30s around the time of the accident. Dense fog was first reported by a weather system at a nearby chemical plant around 1:30 a.m. on Dec. 11. Little wind was also reported.

Based on a 10-year average from 2007-2016, there are roughly 5.8 million vehicle crashes annually in the United States, according to the FHWA, and about 21% of those crashes, around 1.2 million, are linked to the weather. About 70% of weather-related vehicle accidents are due to wet pavement and 46% occur during rainfall. Only 3% happen amid foggy conditions, according to the FHWA.

|

Bill Dyer, 58, a captain with the Bradley County Sheriff's Office in Tennessee, has worked for the agency his entire career. (Photo/Bill Dyer) |

Three decades later, there's not a day that goes by that Dyer, now 58 and a captain with the same sheriff's office, doesn't reflect on the harrowing events of that December morning. He said he thinks about the day of the crash often and particularly when the calendar reaches mid-December. He said what he witnessed that Dec. 11 would qualify for an entire career's worth of tragedy. And to this day, Dyer has never seen a worse fog than what unfolded that day.

"Just a tragic day. A day that changed a lot of people's lives, including my own," Dyer said. "[It's] something I think about every time it's foggy and something I think about every time I pass that area."

For the latest weather news check back on AccuWeather.com. Watch the AccuWeather Network on DIRECTV, Frontier, Spectrum, fuboTV, Philo, and Verizon Fios. AccuWeather Now is now available on your preferred streaming platform.