What is the Oglethorpe Plan? A deep dive into Savannah's historic town design

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

For several months, a debate over the future of historic preservation and growth planning in Savannah's Landmark Historic District has hinged on one document — General James Oglethorpe's 1733 Plan.

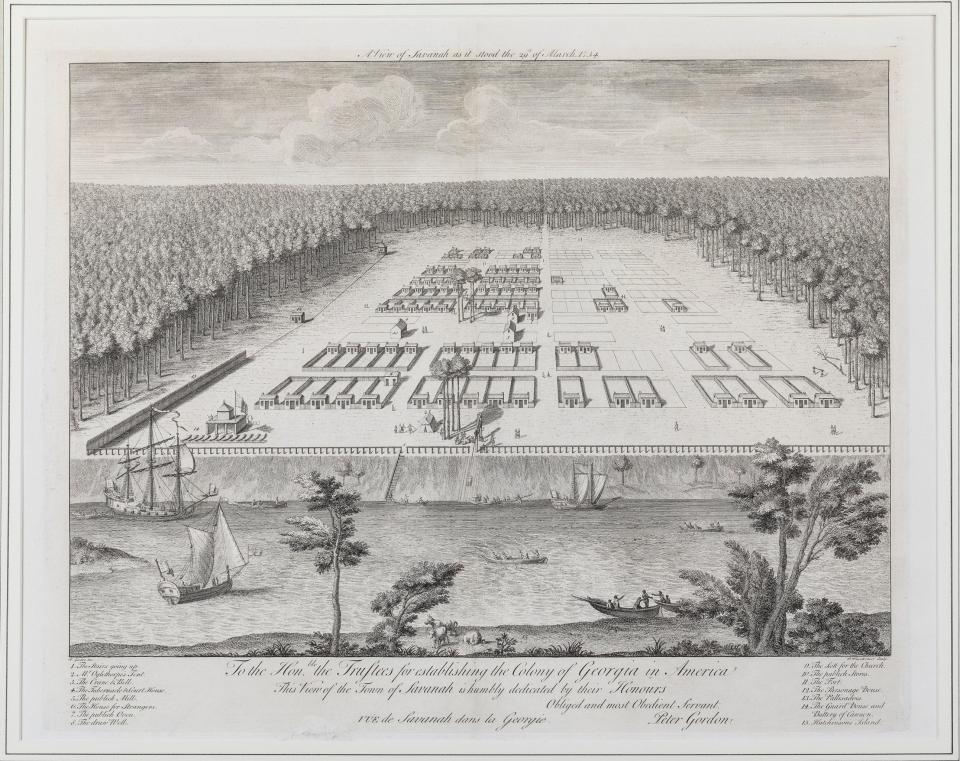

The Oglethorpe Plan, as it's called, was an outline of six wards — squares centering a collection of streets, lanes and lots — that traversed what was then the entirety of the colony. Today, there are 24 wards, and the Oglethorpe Plan serves as a crucial guide in how to preserve downtown's historic integrity.

But what exactly is the Oglethorpe Plan, and why was it created? Several readers have emailed me this question over the past several months. So, below is a deep dive into the Plan, and its future in Savannah.

What is the Oglethorpe Plan?

The Oglethorpe Plan was created by James Edward Oglethorpe, Savannah's founder, as a way to cultivate community and spur economic development.

According to a 2014 paper from Oglethorpe Scholar Thomas D. Wilson and local architect Patrick Shay, the Plan is "a design beloved by residents, adored by visitors, and extolled for its virtues by authorities on city planning and urban design. It is considered one of the world's great plans, comparable in its elegance to the L'Enfant Plan of Washington and the Haussmann Plan of Paris."

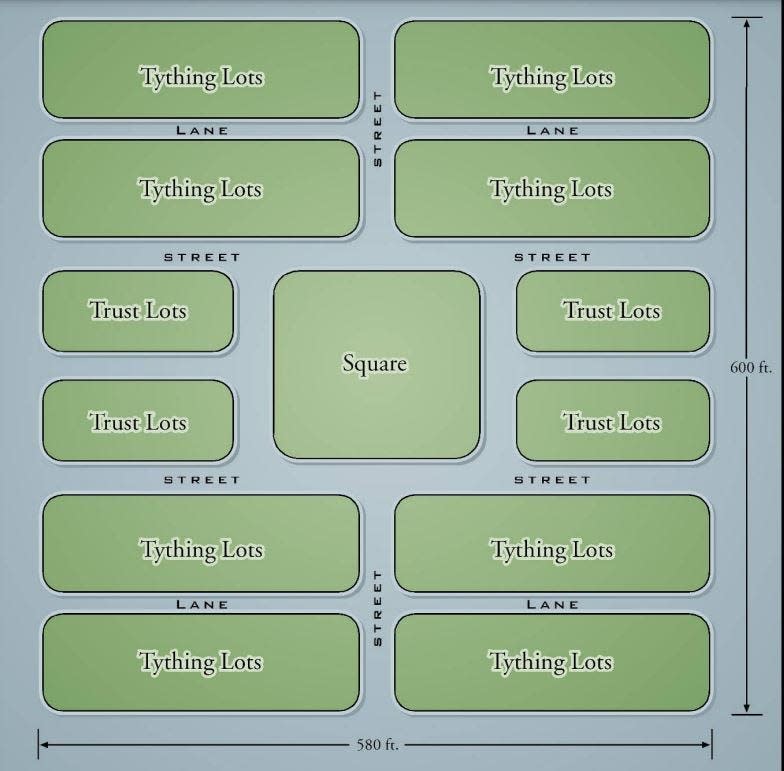

The plan centers on wards, a quad of eight city blocks anchored by a public square. To the east and west of each square sit trustee lots, while the north-south streets are populated with tything lots. Trustee lots were intended to be used for civic buildings — churches, government offices and courthouses, according to the Georgia Historical Society. Tything lots were rows of houses, each colonist who received a tything lot for housing also received farmland outside of the burgeoning colony.

The original plan comprised 60 acres, but the plan now encompasses one-square-mile of Savannah's downtown, according to Wilson and Shay's paper.

Square: A roughly 1-acre plot of land, landscaped and maintained by the city of Savannah, that anchors each ward.

Ward: A 12-acre quad of eight city blocks centered by a public square. Savannah originally had 24 wards, two of which have been lost to development.

Tything Lot: Originally, residential lots that take up the streets north and south of squares. Bisected by lanes. Take up four of the eight blocks in a ward.

Trustee Lot: Largely commercial or government- and civic-related buildings, the lots sit on east-west blocks of each ward.

According to Wilson and Shay, Oglethorpe came to Savannah with his plan already fleshed out. It was the third "utopian plan" to be implemented in the British Colonies, after the Ashley Cooper plan for the Carolinas and William Penn's plan for Philadelphia.

Further south, Darien and Brunswick adopted parts of this plan, which are still visible today.

"It appears likely that Oglethorpe synthesized design elements from a number of sources, including Roman colonial design, Renaissance concepts of the ideal city, and proposals for rebuilding London after the Great Fire of 1666," the 2014 paper states.

As the decades passed and the Historic District grew outward, commercial uses have been widely employed on tything and trustee lots.

Broad streets segregate wards — think of streets that do not bisect squares such as Broughton Street and Oglethorpe Avenue — but serve crucial roles in providing extra space for commercial, civic and residential uses.

Wilson and Shay wrote that the "hierarchy of streets" creates easy-to-navigate intersections that connect wards, and create street views from one ward to the next. "The effect is to make each ward a unique and separate neighborhood, but with a remarkable sense of openness to the larger community," the scholars wrote.

Adapting the plan for today & tomorrow

Today, the plan is a central guide in how the city and local preservationist community approach development and growth, particularly as the Landmark Historic District increasingly becomes a hub for tourism, hospitality and higher education.

"The community has wisely chosen to regulate this development in order to respect the original Oglethorpe Plan through a rigorous design review process and limitations on density that are both prescriptive and visual," Wilson and Shay's paper states. "One important side effect of these limitations is that Savannah remains one of the few cities in the U.S. where people come to leave their automobiles behind."

The walkability of downtown has not been extended throughout the entire city, though, leaving most locals without a built-out system of public transit, sidewalks and bike lanes that would allow anyone living within city limits to abandon a vehicle.

The relevancy of the Oglethorpe Plan in current zoning, design and development decisions made by the city and Metropolitan Planning Commission — the independent planning organization that handles writing the zoning ordinances for several municipalities in Chatham County, including Savannah — has come under scrutiny from preservationists and downtown residents in recent years.

The city's Historic Landmark status from the National Park System has been identified as "threatened," due to developments that degrade the Oglethorpe Plan's integrity, namely the Civic Center on Montgomery Street and Oglethorpe Avenue, which destroyed an entire square when it was constructed in the 1970s, thus destroying the ward.

Debate today hinges on whether the city should stick to a stringent, traditionalist interpretation of the Oglethorpe Plan as it was written in 1733, or if the plan should be adapted and allowed to grow along with the city's needs.

A series of recommendations from the Downtown Neighborhood Association — and supported by a number of entities, including the Historic Savannah Foundation and Tourism Leadership Council — has been submitted to the city and MPC, which will lead public input and ordinance changes as they see fit.

Zoe is the Savannah Morning News' Investigative Reporter. Find her at znicholson@gannett.com, @zoenicholson_ on Twitter, and @zoenicholsonreporter on Instagram.

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: Oglethorpe Plan might be Savannah's template for responsible growth