‘Oh, my God. He made it.’ Tennessee woman sends POW/MIA bracelet to Bradenton vet

By some accounts, as many as 5 million POW/MIA bracelets were produced during the Vietnam War. Each was inscribed with the name of a member of the armed forces who was a prisoner of war or missing in action.

The bracelets were a way for Americans to show support for POWs and MIAs, regardless of how they felt about the war.

Marion Stanford started wearing one in 1970.

Her half-inch metal bracelet was inscribed with the name of Lt. Bradley Smith.

“Even though so many of us hated the war, we had loved ones who served,” she said from her home in Tennessee during a phone interview with the Bradenton Herald.

Her boyfriend, Dan Smith, had been killed during the Tet Offensive of 1968. Now she was wearing a bracelet for another Smith.

She knew nothing about Brad Smith, not even whether he was alive or dead.

As it turned out, Brad Smith was very much alive, although living a miserable existence with other American POWs.

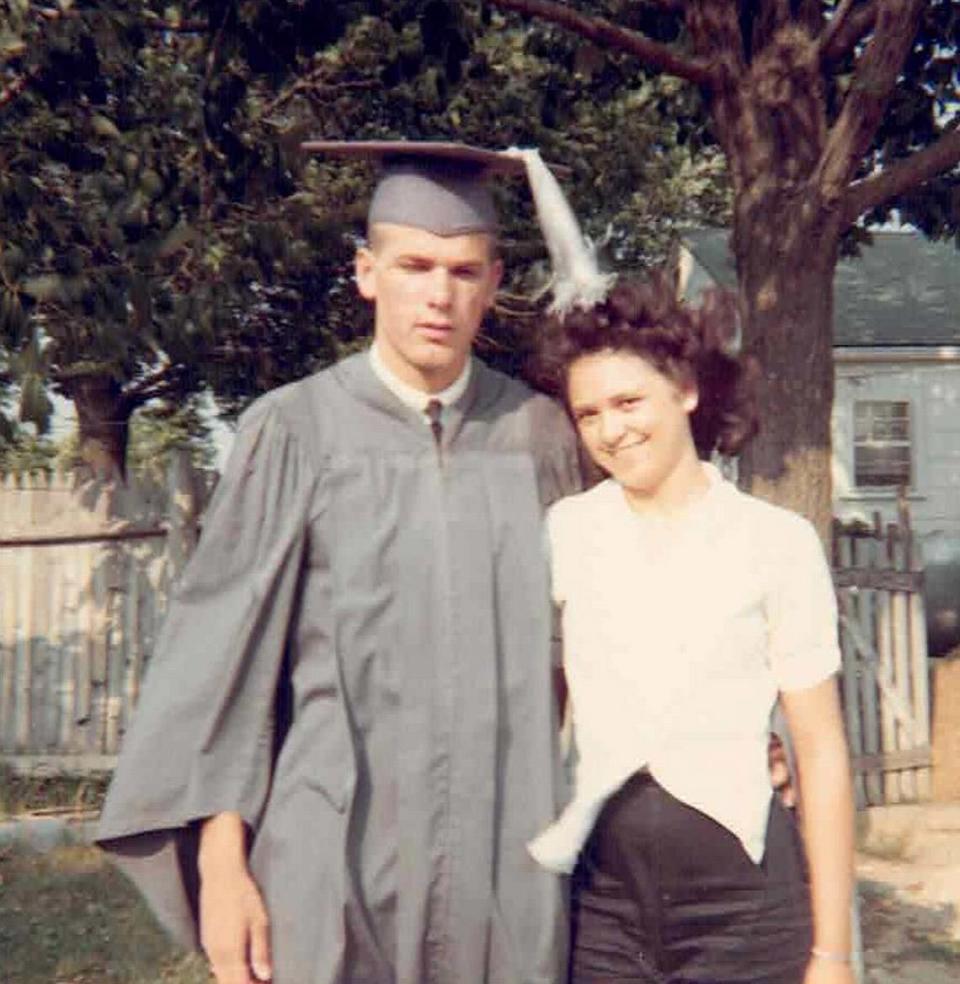

The Navy fighter pilot had been forced to eject over North Vietnam, after the tail on his A-4 Skyhawk was shot off March 25, 1966. He was flying his 77th combat mission over North Vietnam.

He was held prisoner in North Vietnam for 2,516 days, enduring frequent beatings and scavenging whatever he could eat.

When captured, Smith weighed 170 pounds. At the end of the first year, he estimates he had lost 60 pounds, he told a Bradenton crowd in March.

Smith, a Bradenton resident since his retirement from the Navy, made his remarks during a ceremony in Bradenton in March, marking the 50th anniversary of the Paris Peace Accords, which ended America’s combat role in the Vietnam War.

The Peace Accord allowed Smith and 590 other American POWs to be released and come home.

“How do you survive? All you have is the rags on your back and your brain. You are going to eat anything in front of you, no matter how disgusting. You exercise, even if you can only lift an arm or a leg, and you walk. You set goals. You get tougher than rawhide,” Smith said in March.

A revelation

Marion Stanford was one of those who read the Bradenton Herald’s story online about Brad Smith and the release of the prisoners of war.

“Oh, my God. He made it,” Stanford said.

“For years I’ve wondered what became of Lt. Bradley Smith. I was assigned his POW/MIA bracelet more than 50 years ago and wore it for many, many years — long after the war was over. I’ve had many opportunities to dispose of the bracelet — at memorials, etc. I just couldn’t. I wasn’t certain what had become of him and I felt responsible for keeping him alive. I often thought of trying to find out whether he made it home, but research wasn’t as easy then, as now. Recently, I ran across your article in one of my routine searches and I’m certain the commander is my POW,” she said.

She decided to send the bracelet to Smith, in part, to “let him know somebody loved him, whether he knew it or not.”

It’s something of a miracle that she had still had the bracelet after so many years.

Even after the American POWs came home from Vietnam, she continued to wear the bracelet.

“I took a little teasing for it. People would ask me, ‘Are you going to wear it forever?’” she said.

By the early 1980s, she was married and had three children. Eventually, the bracelet ended up in the children’s toy box and some of her babies teethed on it. It also spent time in her jewelry box.

“Those of us now in our 70s and 80s lived in a different time,” Stanford said of the Vietnam War and its effect on a generation.

Meaning to an ex-POW

Brad Smith was released during Operation Homecoming on Feb. 12, 1973. The first stop for the U.S. Air Force aircraft bringing him and other POWs from Hanoi was at Clark Air Force Base in the Philippines.

It was there that Smith received his first POW bracelet with his name inscribed on it. The bracelet was a gift from an airman who had been wearing it.

Smith promptly put the bracelet on his wrist and wore it home to Jacksonville, Fla.

He estimates that over the years, people have given him about 100 of the bracelets. He treasures each and every one of them. The most recent addition to his collection is the one from Marion Stanford.

“It means the American people supported the POWs and were trying to get us out of there. I thank them,” Smith said. “The American people were extremely supportive of us.”

For more information about the history of the POW/MIA bracelets, visit the National League of POW/MIA Families webpage.

National POW/MIA Recognition Day

National POW/MIA Recognition Day was established in 1979 through a proclamation signed by President Jimmy Carter. Since then, each subsequent president has issued an annual proclamation commemorating the third Friday in September as National POW/MIA Recognition Day.

This year, National POW/MIA Recognition Day falls on Friday, Sept. 15.