Ohio State health workers help immigrants detect and treat cancer before it’s too late

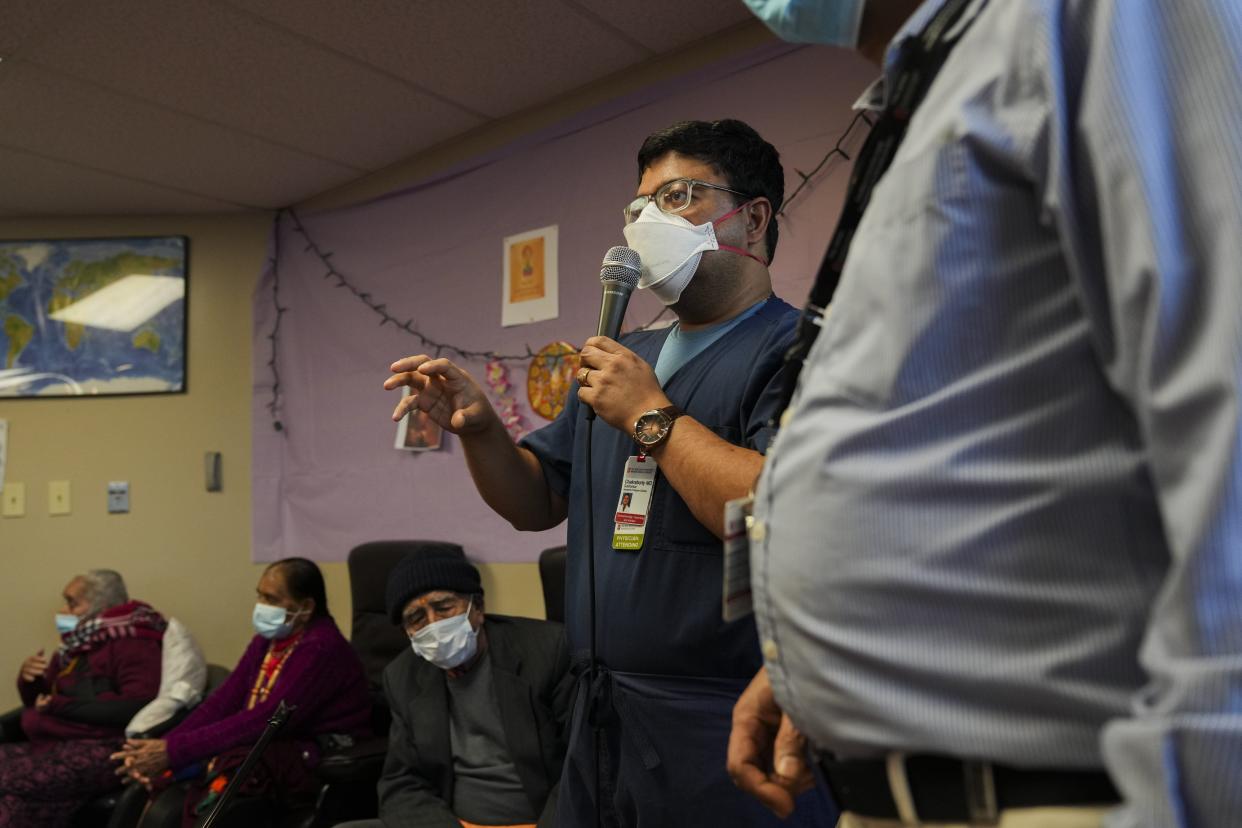

Dr. Subhankar Chakraborty, a physician working at the Ohio State University, stepped into an adult day care center on the East Side on Wednesday to talk to elderly immigrants about cancer.

This was his second time doing an educational session at Himalayan Day Care, which mostly serves older Bhutanese-Nepali residents who came to the United States as refugees. The topic of the day was early detection and treatment for colon cancer, but Chakraborty was there to answer any question that attendees had about cancer and health care.

“How many of you have done a test for breast, skin or colon cancer in the past year?” Chakraborty asked the group of approximately 30 participants. About a third of them raised their hands.

“My wife died from cancer three years back, so I know how having a cancer diagnosis affects every aspect of our lives and our family’s lives,” Chakraborty said to attendees. “This is why we want to detect it early so you and your loved ones don’t have to go through the same thing.”

Chakraborty is a part of a program organized by the university’s Center for Cancer Health Equity, which aims to increase cancer awareness in underserved communities including Hispanic, Somali, Bhutanese-Nepali and other immigrant groups. The team holds regular events at local community centers to educate area residents about when and how to seek help.

Language barriers, cultural concerns and the lack of health-care coverage for low-income residents have made it challenging for immigrants to receive cancer treatment before it is too late, Chakraborty said. Some are also less-familiar with preventive care and cancer screening due to different health-care systems in their home countries, he said.

“Many families we serve didn’t have preventive screening programs in their home countries so that’s not necessarily a part of their natural mindset,” Chakraborty said. “Some of them told me they would choose to wait until they get really sick to get treatment because that means they can spend their limited income on their family's basic necessities.”

Disparities in cancer screenings among immigrant communities

Compared with the general U.S. population, immigrants are less likely to receive screening tests for cervical, breast and colorectal cancer, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Such disparities often lead to worse disease outcomes, the agency found.

COVID-19 has further exacerbated the situation, as many put cancer screenings on hold to prioritize more-urgent health issues, research shows. Nationally, the total number of cancer tests given to women through the CDC’s National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program dropped by more than 80% since the pandemic started.

In central Ohio, limited English proficiency remains one of the biggest barriers preventing immigrant patients from seeking care, according to Hari Pyakurel, a community health worker at the Center for Cancer Health Equity. Even though many hospitals and clinics have access to interpretation services, key information could get lost in the translation process.

“Sometimes patients would give extensive answers, but the interpreter would just summarize everything in one sentence,” Pyakurel said. “There are also regional differences in the language, so the message might not get conveyed properly.”

Kashi Adhikari, who runs Himalayan Day Care, added that some of his clients are illiterate and have a hard time navigating through the health-care system in America.

“Back home, people used to live together collectively, and they could just ask their neighbors to figure out where things are,” Adhikari said. “But here, they can’t easily find someone who speaks their language. They are marginalized and don’t know how to get treatment in a timely manner.”

Read more: Community therapists help Nepali refugees from Bhutan peel back layers of trauma

Long-term outreach to encourage residents to seek preventive care

Hari Chamalagai, a 79-year-old woman living near the day care center, lost her husband to cancer about a decade ago while they were awaiting resettlement in a refugee camp in Nepal.

Back then, Chamalagai did not know much about cancer. Living in a refugee camp where people without financial resources had a hard time accessing health care, the couple had never sought preventive services, she said.

When her husband finally went to a specialty hospital hours away from the camp for the sharp pain in his throat, the doctor told him that he was at the final stage of throat cancer. He died one and a half months later.

“In Nepal, you only get treatment if you have money,” Chamalagai said in Nepali through an interpreter. “My husband would just press a hot towel against his neck to stop the pain. Finally, when we went to the hospital, the doctor said it’s too late and it couldn’t be cured.”

“We learned a lot from this program,” Chamalagai said after attending the Wednesday event. “I know I need to go to the doctor as soon as I feel any symptom and express the problem to them."

In addition to holding education sessions, the team at Center for Cancer Health Equity also helps clients arrange cancer screenings, doctor visits and telehealth meetings so that residents could understand their health conditions before they get really sick, organizers said.

Chakraborty said such outreach efforts require a long-term commitment.

“I came in with the idea that we are going to present them with information on colon cancer, but it turned out to be more of a conversation,” Chakraborty said. “They had a lot of questions about diet and lifestyle. We are just trying to get to know them and understand how to best help them.”

Read more: Here are 10 organizations serving immigrants and refugees in Columbus

Yilun Cheng is a Report for America corps member and covers immigration issues for the Dispatch. Your donation to match our RFA grant helps keep her writing stories like this one. Please consider making a tax-deductible donation at https://bit.ly/3fNsGaZ.

ycheng@dispatch.com

@ChengYilun

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: Health workers address disparities in cancer care among immigrants