Oil gushed into the Gulf and people got sick. A secret Florida warehouse may hold clues

The warehouse looks like countless others in South Florida. But what’s inside is anything but typical.

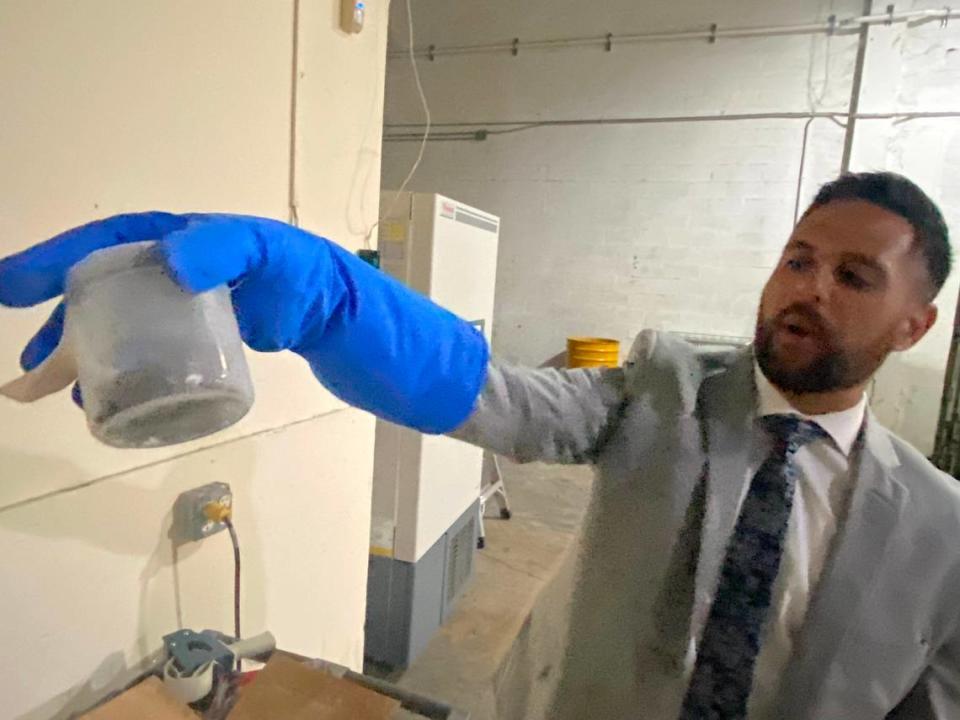

Steel barrels lined up wall to wall. Shelves of vials and jars stacked along the sides of refrigerated storage rooms.

Inside the containers, large and small, are samples from the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill in April 2010 — the largest oil spill in history.

The 127,000 samples — oil, clothing, protective equipment, cleaning chemicals — were collected by BP but are now in the hands of attorneys representing 150 active litigants in lawsuits against the oil giant — people who suffer from various ailments, including cancer.

They say their illnesses were caused either by the crude spewing from the Macondo Prospect in the Gulf of Mexico, or the chemical dispersants used to break up the oil and collect it from the water and soil.

The massive leak started a mile below the surface of the water, 50 miles off the coast of Louisiana, and the oil spread far and wide. The plaintiffs are from Louisiana to South Florida.

“I remember going to the docks and they were talking about an oil spill, and I didn’t think anything about it,” said charter fisherman David Mattiford of Destin, Florida. “I remember hearing about an explosion and how much oil was coming out.”

Over the next 87 days, 134 million gallons of oil gushed from the Macondo well.

Cleanup of the BP oil spill

In the weeks and months after the disaster, Mattiford, 59, said representatives from BP fanned out across the area handing out money and hiring people to work on cleanup crews. He took the opportunity to make some extra cash.

Between June and July 2010, Mattiford and his charter boat crew colleagues headed out into the Gulf and collected oil samples from the water.

Mattiford, represented by Coconut Grove’s Downs Law Group claims that during his time on the crew, he “received continuous exposure to BP’s toxic substances through his oil spill cleanup responsibilities,” according to a lawsuit filed January in federal court in North Florida.

The lawsuit also says Mattiford, other cleanup workers and residents were exposed to “highly noxious chemical dispersants” used in oil collection. Some of these chemicals, the lawyers say, attached to the oil and turned into tiny particles that spread through the air when waves sprayed water mist.

“It became airborne through a method called aerosolation. It was landing on equipment, signs. People were inhaling the oil,” said Dylan Boigris, a Downs attorney working on the cases against BP.

BP spokesman Paul Takahashi said the company “typically doesn’t comment on active litigation.”

“We have nothing to share beyond what is in the court documents,” he said.

The diagnosis

Seven years later, the night before Thanksgiving, Mattiford returned home from work and was watching TV.Something was wrong.

“I felt like I was having a heart attack. I had pain shooting down my left arm, and honestly, it took me about two hours to decide to drive myself to the hospital,” he said in a recent telephone interview with the Miami Herald.

Mattiford took a battery of tests that night, but it wasn’t until the next morning that a doctor gave him the news. He didn’t have a heart attack. He had cancer.

“”You have a tumor on top of your heart,” the doctor told him.

“It was hell. It was hell,” Mattiford said.

Specifically, he had diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. The next month, a biopsy of his bone marrow showed he also had underlying chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

According to the lawsuit, his work cleaning up the BP spill was a “substantial contributing cause” to his illness.

“At the end of the day, we would come in and we’d get decontaminated,” Mattiford said. “Honestly, and I don’t know this for sure, but I think that’s where I got the exposure. They were spraying some sort of chemical.”

‘I’ll never do it again’

Mattiford is in remission, but it was a long struggle to get there, and it wasn’t without lasting consequences.

“I went through hell with the chemo, and don’t think I’ll ever do it again. I think if I got diagnosed again, I just don’t think I could do it,” he said. “I had a port in my chest, and basically, they just kill all your cells.”

Mattiford endured seven rounds of chemotherapy for six hours each session.

“I mean, I lost every hair on my body. My arm hair, everything. My eyebrows, everything,” he said.

Most of his hair has come back, but not as thick as it was.

“But, I am 59 now,” he said.

The lingering effects are in the form of headaches, diminished sense of taste and smell, nerve pain, and cramps in his feet. For about two years, he had a handicap placard for his car so he could park closer, but he no longer uses it because the pain has become something he’s accepted.

“After a while, you just get used to living with something,” Mattiford said.

Acceptance of the pain also manifested itself into a hesitancy to ever go back to a medical professional.

“I gotta be honest, I don’t want to go back to the doctor for fear this is going to pop up again,” Mattiford said. “You know how men are. I gotta be dying before I go to the doctor. Honestly, I get flashbacks from the chemo. I could never do it again.”

The warehouse and the samples

The Downs Law Group took possession of the BP samples in 2019 and placed them in the warehouse, the location of which it does not want oil company to know, Boigris said.

BP tested the samples and used the results to fend off litigation from those believing they were harmed from the spill, Boigris said.

“”Yes, it looked ugly, and yes, we dropped the most oil in the history of oil spills on the Gulf Coast, but don’t worry about it, it wasn’t harmful, it wasn’t toxic,” he said about BP’s legal strategy with the samples.

In 2019, four years after it reached a $20.8 billion settlement with the five Gulf Coast states and the U.S. Justice Department, BP petitioned a judge for permission to destroy all 127,000 samples. Instead, the Downs Law Group took possession of them and had them transported to the South Florida warehouse.

“The only financial burden was taking possession with packing, transport and storage since 2019, which is substantial,” Boigris said. A spokesman for the firm said it has spent “nearly $1 million to preserve these samples and their evidentiary value.”

The law firm is having its own testing done on the samples, saying the testing BP conducted is outdated and was done with the intent of showing the exposure didn’t reach toxic levels.

“So, that’s what we’re here to prove right now. We’re able to take the same samples they tested, we’re going to find better analytical methods with independent laboratories, and we’re going to confirm, one, that the levels of exposure were higher than they’ll acknowledge, but, two, to prove that the data set that they published in somewhat of a summary Excel sheet is not as accurate or precise as they want the courts to believe,” Boigris said.

“That’s a really big issue for the litigation because that’s BP’s wall of defense.”

In addition to the 150 people with active cases against BP, Downs represents about 3,000 people with pending cases against the company. According to Boigris, all suffer from chronic health conditions including cancer and heart, eye, respiratory and skin ailments.

Boigris and his colleagues say the samples in the warehouse are key to proving in court that these conditions are linked to the 2010 oil blowout.

“They’re saying, ‘We did the most testing in the history of oil spills, and you should listen to our testing because it’s the largest one’, not necessarily the best investigation,” Boigris said. “So, we’re attacking the quality of their investigation at this point.”