OKC is closing in on the arena vote — and groups are ramping up their arguments for and against it

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Supporters and opponents of a new NBA arena in downtown OKC agree — the Dec. 12 special election will hone in on what residents truly value in their city's identity for the next few decades.

Where they disagree, however, has broadened over the last couple of months of campaigning before the vote.

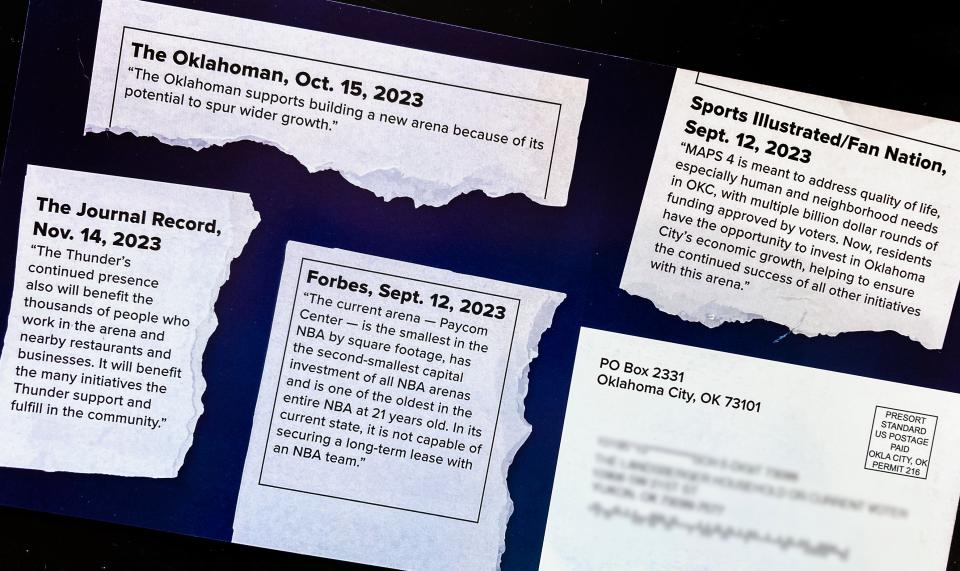

When the finalized proposal was first officially announced in September, proponents of a new arena were quick to argue that a six-year extension of the MAPS program’s one-cent sales tax to fund the arena’s construction was a low price to pay to keep the Oklahoma City Thunder NBA team in town.

“This is the greatest gift we could give the next generation: an assurance that we will be a ‘big league city’ beyond 2050,” said Oklahoma City Mayor David Holt, who has been calling for a new arena since 2022.

“The only alternative is a future without an NBA team, without concerts, without a modern arena, and without all the economic and quality-of-life benefits that we know come with those things,” the mayor said.

More than 60 organizations have voiced public support of the arena proposal, including chambers of commerce throughout the metro area and various business district associations and community advocacy groups. Many of them reiterate the Thunder's philanthropic support of the city's nonprofits and tout the current arena's support of the city's quality of life.

Critics of the proposal question the true economic impact the arena would have on Oklahoma City, as well as the amount put forward by the resident NBA team.

The Thunder ownership agreed to contribute $50 million — or an estimated 5.5% — of the potential venue's proposed minimum cost of $900 million, which critics say puts the overwhelming responsibility of the proposal's burden on taxpayers.

Lobbyist Nabilah Rawdah, executive director of the progressive advocacy group Oklahoma Progress Now, said the proposal amounted to “giving a blank check to seven of the wealthiest people in Oklahoma” at the unfair expense of Oklahoma City’s most vulnerable communities.

“This is overall the worst negotiated deal in NBA history,” she said. “No other NBA arena is paid for 95% by taxpayers. I agree (that) we do need a new arena. I’m pro-Thunder, I’m pro-arena. But it’s the cost, and the question of paying for it. It shouldn’t be us.”

Holt has defended the Thunder's pledged contribution and the broader arena proposal numerous times.

“I think that walking away from it over the issue of a team contribution, even though the deal is actually generally in line with markets our size, is cutting off our nose to spite our face, and we’ll regret it,” Holt said.

Campaign rhetoric shifts to highlighting arena as entertainment venue, not just for Thunder

In recent weeks, the Keep OKC Big League campaign has attempted to highlight additional ways a new arena could continue boosting the city, especially as a venue for music concerts and other attractions.

Christy Gillenwater, treasurer for the campaign and CEO of the Greater Oklahoma City Chamber, said the campaign intentionally emphasized the Thunder's association with the arena because of the team's unifying presence in the city, but that both the current arena and a potentially new venue had many other things to offer.

“That’s something we’ve heard more and more from people is that we’ve had a strong concert presence, too,” Gillenwater said.

“But concerts today don’t have the same standard as they did five years ago, let alone when this arena was built” two decades ago, she said. “It’s a constant change, so we have to be forward-leaning with what kind of set requirements they’ll have.”

Chris Semrau, general manager of Paycom Center, said the city needed to remain competitive with a cutting-edge facility that could continue to draw major concert acts and other types of entertainment.

“In 2022 we were ranked 48th in worldwide concert ticket sales," Semrau said of the current arena. “However, competition for the biggest artists continues to increase year after year, and there are more new venues competing for these events all of the time, which is going to make it difficult long-term to secure the same level of content in the future.”

If the proposal passes Dec. 12, Semrau also said a new arena could prove transformational for the community, "with events that will seek out coming to (the) new venue that you haven’t even thought of yet." He added that some sports organizations already are beginning to consider bids for events from 2028 through 2032.

“If your expectation and desire is to have a significant number of the largest tours in the country, different types of family shows, and elite sporting events, then we need a proper, modern facility to help us compete for those. Without supporting this measure on Dec. 12, you must reset your expectation if we don’t get that level of event activity in the future. We simply can’t have it both ways.”

More: How much is OKC's identity worth? NBA arena plans spark debate among local leaders

Economists voice concern over 'biases' in study on arena impact

More than 20 economists with Oklahoma ties have voiced opposition to the proposal, pointing to decades of peer-reviewed academic research on publicly financed sports stadiums and arenas, which overwhelmingly shows heavy skepticism of such subsidies generating net new spending and causing economic growth.

On Dec. 5, several of them gathered in a panel to voice their continuing concerns. The economists began organizing public discussions ahead of the vote after an arena impact study was released in November by Applied Economics, a consulting firm based in Arizona, which claimed that construction of a new OKC arena could generate up to $1.3 billion.

Cynthia Rogers, an economics professor at the University of Oklahoma, said she finds "the misinformation and misrepresentation" of the recent study "troubling," and Brandli Stitzel, a Texas-based sports economist who studied at OU, agrees.

More: OKC officials say a new Thunder arena is worth every penny. Economists aren't sold.

Stitzel said “several core problems” showed in the study’s methodology, including biases in categorizing the costs of labor and construction as benefits and the use of what he described as “an arbitrary number” in calculating the economic multiplier. He also pointed to previous research he had conducted in the years after the Thunder arrived in OKC, showing that NBA activity at the then newly revamped arena largely shifted spending to eateries in its downtown proximity at the expense of other entertainment options in the city.

“At the end of the day, you need to view a sports team or any other sort of major project like this as an amenity," Stitzel said. “What are you willing to trade off in terms of your tax burden, and would you rather have the Oklahoma City Thunder, or would you rather have this tax relief?"

More than just Thunder: Could a new NBA arena redefine the concert scene in OKC?

Campaigns on both sides in a battle of funds, fighting low turnout

To rouse civic engagement ahead of the vote, supportive and oppositional campaigns of the arena proposal have both devoted funding to various forms of outreach since September.

Nick Singer, spokesman for Oklahoma Progress Now and the Buy Your Own Arena campaign, said the opposing campaign has operated off of "a very, very modest budget," largely driven by grassroots donations, and told The Oklahoman he would share more information about the campaign's financing and spending after the election.

Spokespeople with the Greater Oklahoma City Chamber, which is running the Keep OKC Big League campaign, provided The Oklahoman with records showing at least $478,000 in advertising purchases since Nov. 20 on Oklahoma City's five major television stations. Gillenwater said that, after months of planning, the funding for advertising came from the chamber's budget, which is sourced from membership dues and donations but does not include any taxpayer allocations.

Tyler Moore, the Keep OKC Big League campaign manager, said internal polling indicated high enthusiasm in favor of the arena proposal. Campaign supporters are busy in the final week before the election distributing signs and promotional materials to local restaurants and bars, Moore said, but staffers are careful to not assume voters would approve the proposal overwhelmingly.

“You know, any special election, I don’t like to dream too much of blowouts. It’s a smaller electorate, smaller universe, smaller turnout — that’s just how it’s gonna be,” Moore told The Oklahoman. “People are making a lot of predictions, but I think we’re going to be healthily over the margin.”

Voter turnout for special elections in Oklahoma City is historically lower than primary and general elections centered around high-profile politicians, and residents have often not shown up in high numbers even for local initiatives meant to directly improve the city. The ambitious MAPS 4 project passed in December 2019 with only 7% of the city population casting a ballot.

“People also forget that ... the third MAPS (proposal) barely passed, and I imagine it polled well then, too," Moore said. "So, we can’t just trust that and put it all in the poll — we’ve got to do everything we can and act like we’re behind regardless, so that’s what we’re working to do.”

This article originally appeared on Oklahoman: OKC Thunder arena vote: Who is for and against a new arena?