Oklahoma City establishes human rights commission for first time since 1996

Oklahoma City established a human rights commission Tuesday for the first time in more than a quarter century.

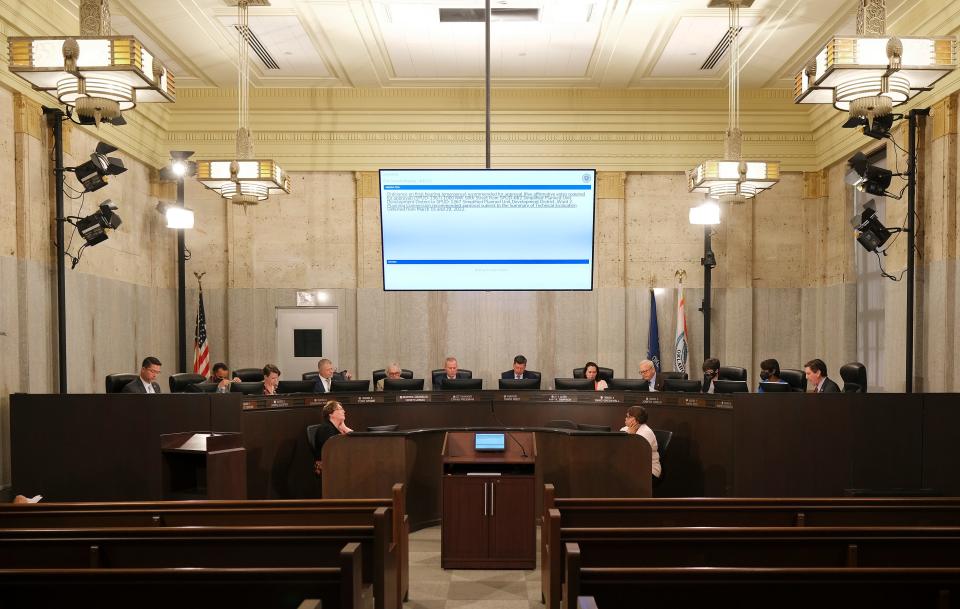

The new nine-member commission — whose members will be suggested by council members and appointed by the mayor — will be charged with investigating and addressing employment, housing and public accommodations discrimination complaints. During more than 90 minutes of public comments from 38 residents, proponents said the commission will ensure a clear route to managing discrimination in Oklahoma City, while critics said the commission represented government overreach at Tuesday's city council meeting.

The Oklahoma City Council approved forming the commission by 5-to-4 vote, with councilmembers Bradley Carter, Barbara Young, David Greenwell and Mark Stonecipher voting against.

More:Oklahoma City to begin implementing 39 police reforms following city council vote

Plans for the commission were formed with the help of a task force formed by Mayor David Holt in the summer of 2020, amid the social unrest and racial justice reckoning after the Minneapolis police killing of George Floyd.

The city's previous human rights commission was disbanded by the city council in 1996 after commissioners sought to extend protection to the city’s LGBTQ+ residents. Then-councilor Jerry Foshee, Ward 5, said the commission's goal was "to give rights to the gays, the lesbians, the people who have had sexual changes and things of that nature," and the commission needed to be disbanded to keep the issue from returning to council, according to The Oklahoman archives.

Holt said the vote to reestablish the commission was an example of compromise between a politically diverse city council, and "validated once again that all are welcome in Oklahoma City and all are loved."

Today, for the first time in a generation, the people of Oklahoma City live in a community with a Human Rights Commission. 🧵

— Mayor David Holt (@davidfholt) July 19, 2022

Ward 4 Councilor Todd Stone was a member of the task force and said he supported the commission as an educational opportunity. Though many of the residents who spoke Tuesday were critical of the commission, Stone said he had to vote in its favor.

"I hate to disappoint people, but I have to vote with my heart," Stone said, before using the common acronym for "What Would Jesus Do?"

Is the Human Rights Commission needed?

Many of the commission's opponents said it was more divisive than unifying. Linda Curtis, who lives in Ward 8, said it would create contrast between groups rather than solve issues.

"We have come a long way, and I'm old enough to see that we have made a lot of improvements in our country," Curtis said. "And I'd like to not bring up more problems ... more contention. And I feel that's what this commission would do."

Stonecipher, who represents Ward 8 and was a member of the mayor's task force, said after hours of meetings and research he felt the commission was unnecessary due to the state and federal avenues that exist to address discrimination.

"As always, I went into this process with an open mind. ... The more I researched the clearer it became to me that the proposed city commission would be duplicative," Stonecipher told The Oklahoman via text. "I think it is best for OKC to focus on our core responsibilities and leave these matters to other levels of government."

Residents currently can file a discrimination complaint through the city manager's office, and it would then be referred to the necessary agency. This process has been in place since the 1970s, though city attorney Paula Kelley said she could find no record of anyone filing a complaint.

"Zero people using it lets me know that no one knows about it," said Andrea Benjamin, task force co-chair and University of Oklahoma associate professor.

A SoonerPoll survey of Oklahoma City residents, funded by the Arnall Family Foundation for the task force's research, found that 70% of respondents felt they had experienced discrimination. Two-thirds of respondents said they felt discrimination or harassment was a problem in Oklahoma City.

The commission will serve not only as a form of reporting but also to bring more awareness to the issue of discrimination and what options victims have, Benjamin said.

Some commenters opposing reestablishing the commission said Oklahoma City was past discrimination based on someone's race, ethnicity, sex or gender. Ward 2 resident Nadine Smith said, addressing Ward 2 Councilor James Cooper, that God can "deliver" people from homosexuality. Cooper is the city council's first openly LGBTQ+ member.

The Rev. T. Sheri Dickerson, president of Oklahoma City's Black Lives Matter chapter and a member of the task force, said she was "shaken" by some of the comments that she said were "harmful" and "weaponizing Christianity."

"My God, please allow humanity to win today," Dickerson said in a plea for the city council to establish the commission.

How much money will commission cost the city?

Another objection to the commission from those who spoke Tuesday was the idea that the city was putting millions of dollars into the commission.

Jane Abraham, the city's community and government affairs manager, said the only financial investment in the task force was the time staff spent in meetings and research.

The financial impact of the commission will be "minimal," Stone pointed out.

Once the commission is formed, City Manager Craig Freeman will designate a compliance officer who will have the first look at complaints. This could require a new position but also may be filled by an existing staff member. The commission also will put on an annual educational event, which could cost the city $10,000 to $20,000, according to a financial impact report.

Commission members will volunteer their time, like all of the city's boards and commissions.

How will discrimination complaints be handled?

The compliance officer will review complaints with a city attorney and determine whether it should be referred to another agency or whether the complaint should be investigated by the commission.

An investigation can either lead to dismissal of the complaint or an attempt by the commission to conciliate between the complainant and the accused party. If an agreement cannot be reached, or if the Conciliation Order is broken, the compliance officer can choose to refer the case to an outside agency.

The commission cannot handle complaints involving a city official or employee acting in their employee capacity, including police officers. It also must adhere to current protections under state law, which does not include sexual orientation or gender identity as part of its definition of sex and gender.

The task force has recommended adding specific protections for LGBTQ+ residents and giving commissions the authority to provide restoration for discrimination victims to the city's state legislative priorities for 2023.

Oklahoma City joins Tulsa, Lawton and Norman as Oklahoma cities with human rights commissions.

This article originally appeared on Oklahoman: Oklahoma City council establishes nine-member human rights commission