Oklahoma Democrats, a once powerful party, look to rebuild

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Drew Edmondson has four pieces of advice for anyone wanting to run for statewide office as a Democrat in Oklahoma — become familiar with a firearm, figure out how to explain your positions to a voter who disagrees with you, raise a lot of money, and learn to play the guitar or “something else that makes you a little more folksy."

The advice comes from one of the last Democrats to hold statewide office in Oklahoma — attorney general from 1995 to 2011 — who also saw firsthand the challenge the party currently has in appealing to rural voters when he lost a 2018 bid for governor.

But despite Edmondson’s desire to see his party rebuild its rural roots, he isn’t sure it’s an achievable goal.

“If we ever start winning statewide races again, like the governor, I think it can only happen because the voter share in Oklahoma City and Tulsa outweighs everything else,” Edmondson said during a recent interview in his Midtown Oklahoma City office. “But I don’t know when that will be.”

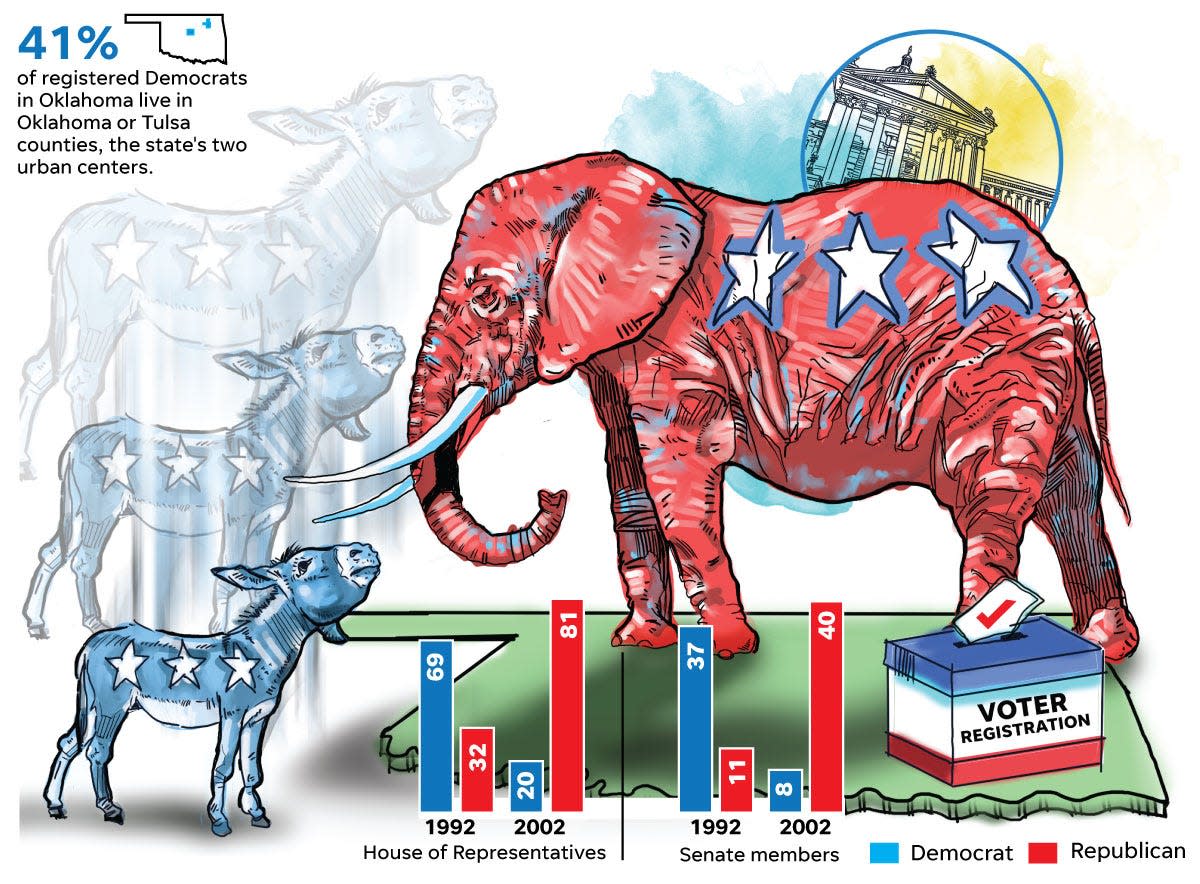

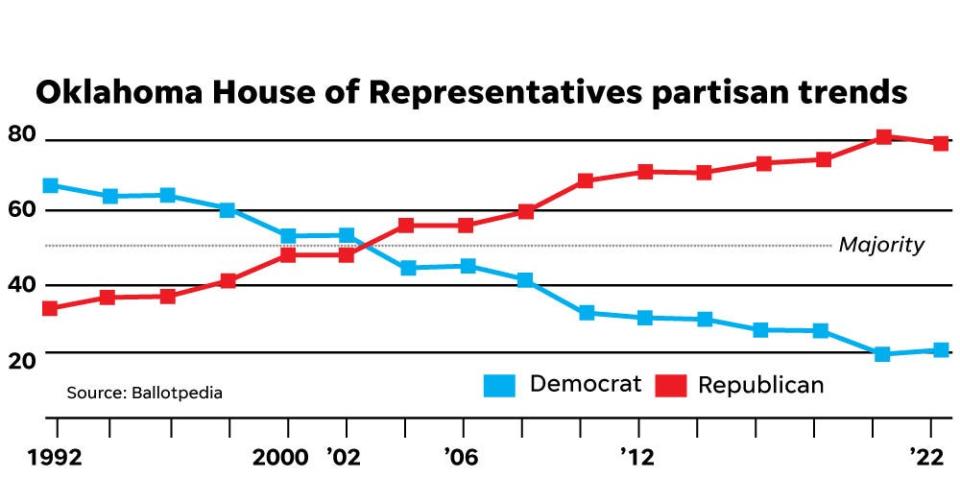

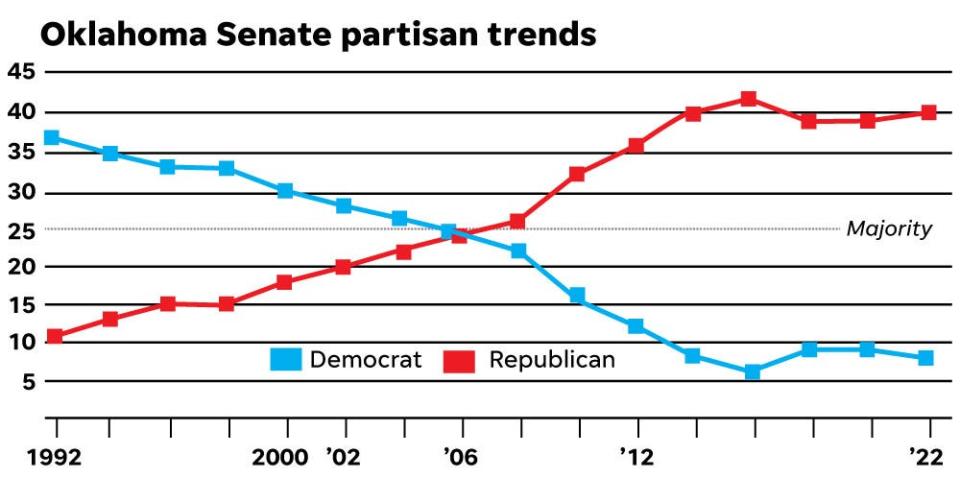

Democrats enjoyed nearly a century of local political dominance — four out of five state legislators in Oklahoma were Democrats from statehood to 1973 — largely because of its appeal to rural voters, especially in the southeast, a region dubbed "Little Dixie" because of political and cultural ties to the southern United States. The reverse is true today as Democrats have been relegated to a party primarily in urban communities.

Whether the party should try and rebuild its once great rural wall or exclusively focus on urban communities is one of the biggest internal debates among Oklahoma Democrats, according to interviews with more than two dozen current and former lawmakers, official party leaders, community-level activists and campaign strategists.

More: State Board of Education meetings have become theater of political conflict

Some believe the party has become too progressive to appeal to rural voters and that Democrats should focus on electing city councilors and school board members within the state’s largest cities.

Others said they had studied Republican states that have seen recent Demcoratic gains and believe there are examples to replicate in Oklahoma.

“Places like Kansas and Georgia inspire some hope,” said Emily Virgin, the House Democratic leader from 2018 to 2022.

Trying to understand the current state of the Democratic Party in Oklahoma can appear a frivolous task when you consider the party has so few seats in the state House and Senate its legislative efforts are often irrelevant — just 15 bills led by Democrats were passed out of the Legislature this year, according to an analysis by Oklahoma Watch.

A little more than 650,000 Oklahomans are registered to vote as Democrats, half the number from 20 years ago, and no Democrat represents any of the state’s five U.S. House districts or either of its two U.S. Senate seats.

However, the state’s largest urban neighborhoods and most significant commercial districts are largely represented by Democrats, making the party a relevant force within corporations, universities and media operations.

For Democrats in Oklahoma, not losing is winning

A generation ago, a Republican majority at the Oklahoma Capitol was nearly unthinkable. When Edmdonson won his Demcoratic primary for attorney general in 1994, the conventional wisdom was he would easily win the general.

“I thought it was basically over,” Edmondson recalled about his 1994 primary win. “But we ended up being damn lucky (to win the general).”

Republicans won the governor and lieutenant governor races that year, made gains in the state Legislature and won nearly all congressional seats.

Like many Southern states, Oklahoma had been red in presidential races since the 1960s — “We’ve lost the south for a generation,” former Democratic President Lyndon Johnson reportedly said after signing the Civil Rights Act in 1964. But Oklahoma Democrats continued to hold legislative majorities over the next 30 years.

In the early 1990s, Republicans began to make local gains by pushing conservative politics that appealed to the Christian right. Movements aligned with an anti-government and evangelical worldview took root in Oklahoma, including the "Republican Revolution" of the 1990s, the Tea Party of the 2000s, and the rise of Donald Trump over the last decade.

Oklahoma's political map essentially has reversed over the last few decades as Republicans became the party of rural and suburban counties, which continue to drive statewide races.

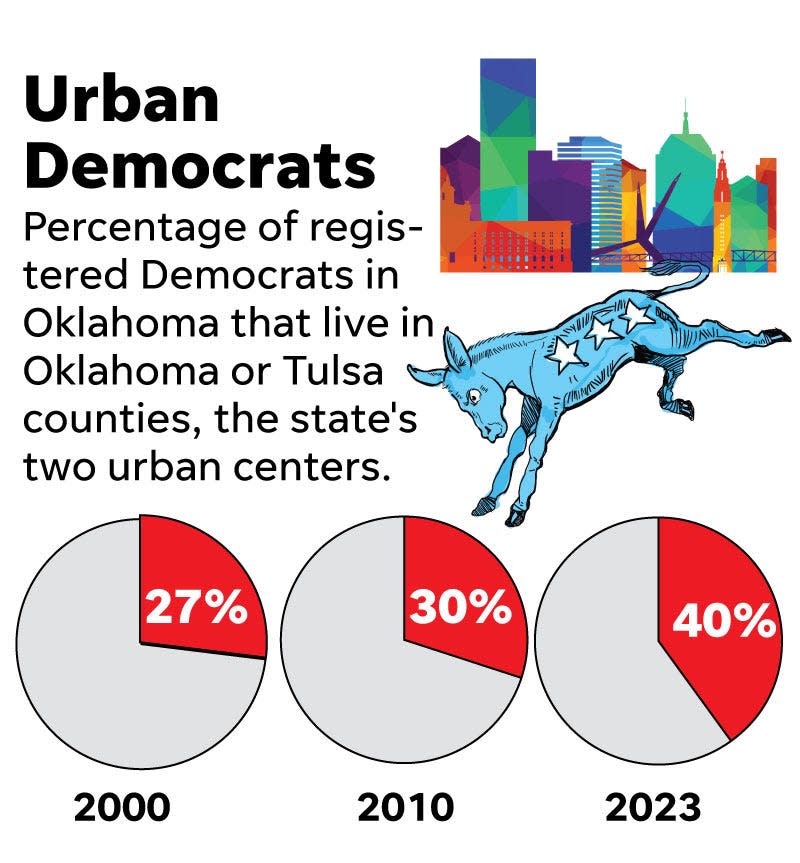

In 2000, only one out of every four registered Democrats lived in Oklahoma or Tulsa counties, home to the state’s two largest cities.

Today, 41% of all Democrats live in either Oklahoma or Tulsa counties, according to voter registration data.

In looking for hope, Democrats point to urban districts where the party has seen recent success.

More: Oklahoma's medical marijuana agency 'ready to really get going'

Alicia Andrews, the party’s state chairwoman, was excited to see Democrats successfully defend their state House and Senate seats last year.

“Just retaining seats was actually a gain when you consider how much we had been losing seats in recent years,” Andrews said. “But we also picked up a (House) seat (in Tulsa).”

Andrews doesn’t predict Democrats will return to majority status in the state Legislature like it was 20 years ago. But she hopes the 2022 elections are a base to build on.

Gaining six seats in the House and five in the Senate would allow the party to block the Republican supermajority on tax-increasing votes, something Andrews and other party leaders said is a top goal over the next decade.

“We have a plan to break the supermajority by 2030," Andrews said. “But if we want to flip four seats, we have to target way more than four seats, and we have to run statewide.”

Within the party, urban vs. rural becomes a defining line

Flipping seats is how Cyndi Munson became a state representative from Oklahoma City. Munson, who is now the leader of the Democratic House caucus, initially lost her challenge of a longtime Republican representative in 2014 before winning the seat when it became open the next year.

Munson’s win was followed by a mini-wave of Democratic success as the party picked up several more House and Senate seats in neighboring northwest Oklahoma City districts.

“I represent all of Nichols Hills, The Village and other parts of Oklahoma City that a Republican has historically held,” Munson said. “We’ve had a lot of success in this area, but I think there are still tons of opportunities in Oklahoma City and Tulsa, especially as demographics shift and Oklahoma City continues to grow.”

Like Andrews, Munson said breaking the Republican supermajority should be the party's next goal. To do that, Munson said the party plans to focus on Republican districts where Joy Hofmeister, last year’s Democratic candidate for governor, overperformed.

“I'm not living in some fantasy world where we're gonna get some kind of majority or anything like that,” Munson said. “But growing our party is not some farfetched idea.”

Some Democratic leaders and strategists told The Oklahoman they believe legislative seats in the Oklahoma City and Tulsa suburbs might be possible to flip. But many said rural seats are tougher because as the party has become more urban, it has also become more progressive.

A Democratic candidate running for a House or Senate seat in Oklahoma City might be more vocal about abortion rights, support for LGBTQ+ communities and limiting firearm access, which creates a challenge for statewide Democratic candidates who have often tried to present a more moderate campaign.

“I think there's a ton of pressure from moderate Democrats to grow the party's membership in rural areas or at least stop the bleeding, and I think that’s misguided,” said Jess Eddy, an activist in Oklahoma City and a former Democratic House candidate.

Eddy said the Democratic Party’s growth areas stem from young leaders driven by a commitment to racial justice and equal rights, a platform not always easy to sell to conservative voters.

“What I think would benefit the most Democrats is for the state party to invest their resources in urban races and municipal races,” Eddy said. “I mean, I just think that we've lost the rural vote for decades, and I don't think it's coming back anytime soon.”

While school board and municipal races aren’t technically partisan, Democratic candidates have gained some of those seats in Oklahoma City.

But Andrews, the party’s state chair, isn’t willing to concede rural Oklahoma.

“We don't grow our party if we are just the party of Oklahoma City, Tulsa and Norman,” Andrews said. “And frankly, I believe that we are the party that believes that we all do well, when we all do well. And that includes our rural neighbors.”

Andrews said she wants the party to shift to a more neighborhood-level organizing system, especially in rural communities currently grouped by counties. It's a model she said has worked in states like Nebraska.

"If you don't live in the county seat of some of these counties, you can be driving 45 minutes to where some of our county meetings happen," Andrews said. "But if you have a (neighborhood) setup, you can drive a mile or a couple of blocks and meet with a lot of Democrats near you."

In several interviews, local party members also mentioned Kansas as an example to follow. The Republican state currently has a Demcoratic governor and recently preserved abortion rights in a statewide election. Others pointed to Georgia, where voters supported President Joe Biden three years ago and elected two Demcoratic candidates to the U.S. Senate.

Those states have similarities, yet key differences.

Georgia has a larger Black population, and the metro area of Atlanta is bigger than the entire state of Oklahoma. While Kansas has similar demographics to Oklahoma, it also has fewer evangelical voters, a key demographic for Republicans.

But Oklahoma Democrats say the biggest lesson from other states is that success is years in the making.

“It’s easy to look at a state like Georgia and get excited, but the success there didn’t just happen in one election cycle,” said Virgin, the former House minority leader. “That was built over a decade or more, and I think that has to be the mindset here.”

This article originally appeared on Oklahoman: Oklahoma Democrats, once a powerful party, are looking to rebuild