How old is your dog? You can’t just multiply human years by 7, scientists say

Turns out the old “multiply by 7” rule to calculate a dog’s age in human years isn’t quite right.

Researchers from the University of California San Diego studied dog genomes to figure out just how old our canine pets are compared to human years, and it’s a little more complicated than simple multiplication.

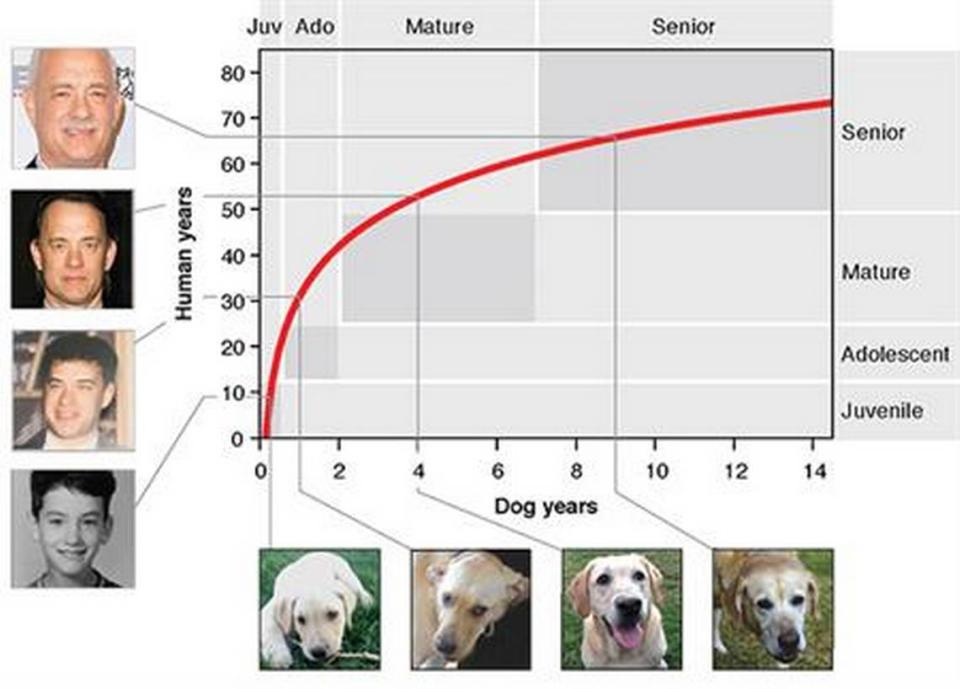

Under the well-known formula, a 1-year-old dog would be about 7 in human years. But now the researchers say a 1-year-old dog is more like a 30-year-old human.

A 4-year-old dog is closer to a 52-year-old person, the researchers found. But after seven years, aging slows down in dogs.

“This makes sense when you think about it — after all, a nine-month-old dog can have puppies, so we already knew that the 1:7 ratio wasn’t an accurate measure of age,” said lead researcher Trey Ideker, a professor at the UC San Diego School of Medicine and Moores Cancer Center.

The researchers studied the genes of 104 Labrador retrievers, with an age range of 16 years.

“I have a six-year-old dog — she still runs with me, but I’m now realizing that she’s not as ‘young’ as I thought she was,” Ideker said in a press release from the university.

The researchers published the new findings Thursday in the academic journal Cell Systems.

“All mammals, whether dog, human, or other creature, pass through similar life stages of embryogenesis, birth, infancy, youth, adolescence, maturity, and senescence,” the researchers wrote in the paper.

They decided to explore how dogs age to learn more about how genes change as people (and Labradors) get older.

“More than just a parlor trick, the researchers say it may provide a useful tool for veterinarians, and for evaluating anti-aging interventions,” the university said.

“There are a lot of anti-aging products out there these days — with wildly varying degrees of scientific support,” Ideker said.

“But how do you know if a product will truly extend your life without waiting 40 years or so? What if you could instead measure your age-associated methylation patterns before, during and after the intervention to see if it’s doing anything?” Ideker said.

Tina Wang, a former graduate student in Ideker’s lab at the time, is the lead author on the study. Wang, Ideker and the other researchers say they’ve developed a new “epigenetic clock,” which can help show the age of cells based on chemical changes in their genes.

The changes are “much like wrinkles on a person’s face provide clues to their age,” the university said.