Once Again, the History of Witch Trials Has Inspired the World’s Most Annoying Merch

This piece was adapted from a post on Eleanor Janega’s blog, Going Medieval.

The other day, I was minding my own business online, just trying to survive in a world of unrelenting horror, when suddenly I was served an ad. Maybe the algorithm has figured out that I am mates with a bunch of the people who appeared in the BBC’s Witch podcast, which was released earlier this year. It has certainly gleaned that I am a woman, I tend to read things about history, and I am interested in feminist theory more generally.

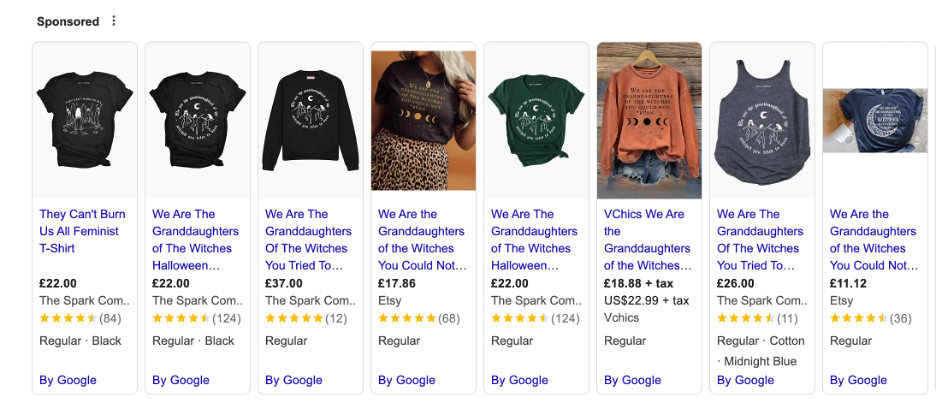

Hilariously, what that means is I am often served ads for this schlock:

This winds me up no end, and I want to explain why. After all, enough people seem to find this idea radical that you can buy variations of this twee-ass shit on shirts, notepads, wherever.

Yeah, OK, you might say. It’s a bit basic, but is it bad?

Yes, I would argue, yes it is. For a couple of reasons.

The first and most obvious one is that the women who were killed during the early-modern witch trials were not, in fact, witches. They were just people.

This is not to say that some of those accused of witchcraft didn’t confess to it on occasion, or maybe even think they were doing some witch-ass stuff. But that doesn’t mean they were actually doing it.

Medieval people were usually pretty clear on that, unlike the people making these stupid shirts. The 10th-century monk Regino of Prüm’s Canon Episcopi, for example, had this to say about the idea that witches flew off at night:

It must not be omitted that some wicked women, turned away after Satan and seduced by the illusions and phantasams of demons, believe and profess that, in the hours of the night, they ride upon certain beasts with Diana, the goddess of the pagans, and an innumerable multitude of women, and in the silence of the dead of night traverse great spaces of the earth and they obey her commands as of their mistress, and are summoned to her service on certain nights.

This is an important point. People might think they were doing some pagan stuff and hanging out with Diana, but in fact they were just delusional—and, this monk argued, if they thought this, they needed religious intervention because they had been deceived.

In the later medieval period, before we get into the modern witch panics, you occasionally got women who were found by inquisitorial boards to be guilty of witchcraft when they were being investigated for heresy. This is important, for reasons I will make clear later.

Anyway, this was the generalized approach put forward by the 13th-century Pope Alexander IV. In his 1258 papal bull Quod super nonnullis, he ordered inquisitors to generally avoid investigating sorcery unless what was happening “clearly savoured of manifest heresy.” This remained pretty much the approach for the rest of the medieval period. If people were messing around, doing stuff where they thought they were sacrificing to demons or something, you could get in trouble for that and excommunicated for heresy. However, it wasn’t the main thing that inquisitors were meant to be worrying about, because it was mostly just stupid.

I would argue that this is still bad, even if it’s not a death sentence per se, because it was still a way of cutting people off from their communities by exiling them from their churches, which isn’t great. Even if they think they are in a dialogue with a demon or whatever. But the point is, for a long time, the way people approached sorcery was: That’s weird. You’re being weird and not Christian.

In the early-modern period, things got a lot worse in this arena, as they did in several areas of life. (I wrote a book about it. Go read that.) Suddenly, you had a bunch of Protestants around the shop, and they were in a religious arms race with the church to prove who was the most holy. And a great way of proving you were holy was to go around yelling that women were witches. They still weren’t. Instead, they were women who had money that other people wanted. Or women who performed abortions. Or women who begged. Things of this nature.

And occasionally they still sorta thought they were witches? Or sometimes told people that to scare them. During the Pendle witch trials in 1612, for example, Alizon Device absolutely told a court that she had sold her soul to the devil and had lamed a certain John Law after he refused to sell her some pins. Anyway, she got killed. A lot of her family got killed. A bunch of people got killed. But they weren’t witches. Alizon just … had a lot going on. Because you cannot, in fact, sell your soul to the devil and get the powers to take out people’s legs in return. That is a fact.

It’s even more of a fact that the great majority of people who were killed for witchcraft did not think they were witches. In the majority of cases, if they confessed that they were witches, it was usually because they had been tortured repeatedly and at length in order to obtain a confession, as was the case in the Salem witch trials, for example. These were people who faced horrifying punishment for absolutely no reason, then were killed.

So, when you go around wearing a cute little shirt talking about “the witches they couldn’t burn,” you are calling all of these innocent people witches. And they weren’t. You are doing exactly the same thing as all those gross Puritans or inquisitors. You are being worse than the medieval Catholic Church because at least they would say, That witch stuff isn’t real.

Secondly—another thing about people who were falsely found guilty of being witches—they usually weren’t burned. They were more commonly hanged. The confusion here, I think, stems from the earlier medieval conflation of sorcery with heresy. ’Cause you know who was burned at the stake? Heretics. My boy Jan Hus? Burned at the stake. People who got prosecuted for witchcraft as a part of heresy trials in the medieval period? Sometimes burned! The people accused of being witches in the modern period? Not so much!

Occasionally, people who were accused of witchcraft were burned, but that was more typical in Catholic places, like southwestern Germany, that were still adhering to prosecuting witchcraft as heresy. Overall, if you were getting killed for witchcraft, odds were it was the less flashy hanging route for you.

This is not to excuse the burning at the stake of heretics, who, I think, should not in fact have been killed for not being the right kind of Christian. Nor is it to say that being hanged is somehow a better way to die than being burned and that, therefore, this excuses what happened. Instead, what I would argue is, if you are gonna produce merch that makes light of the estimated 30,000 to 60,000 people who were killed over the 300-some years of the witch panics, you could at least get the facts straight.

Also! These shirts with their pictures of women and their references to being a “granddaughter” of the women killed as witches obscure the fact that, of those thousands of people killed, many were men. This isn’t to say that women didn’t account for a greater number of those who were killed, because they did. However, in Europe, a good 10 percent of the total number of people killed as witches were men. This gender breakdown also varied from region to region. For example, in Iceland, of the 22 people who were killed in witch trials, 20 of them were men. This probably has to do with a local understanding of sorcery as a learned skill that required Latin. (Because, as we all know, the demons of hell speak Latin.) We see a similar pattern in the Baltic witch trials, in which about 60 percent of those killed were men. One of the most horrific of the Salem trial killings was that of Giles Corey, who was slowly crushed to death by having rocks piled on him after he refused to admit that he was a witch.

I say this not to “well, actually” the remembrance of the witch panics but to point out that the entire thing was a disgusting waste of human life and that everyone who was killed deserves to be recognized as a victim. These were horrible violent actions, and the men killed in Iceland, or Estonia, or the American colonies were just as innocent and valid as the women who suffered alongside them. If we’re doing commemoration, then let’s do it.

All of which brings me to my last point about why this is unacceptable: All those algorithms trying to sell me a factually incorrect T-shirt are directly profiting off selling a lie rooted in the pain and death of thousands. Gross! The innocent people who were killed in one of the darkest periods of human history deserve our respect and are not, in fact, a cute little way to make a quick buck. There’s no way to argue that this is a respectful commemoration, because they haven’t even bothered to get the basic facts straight. There’s no way to argue that it’s a feminist statement because it directly plays into misogynistic lies about marginalized women in order to try to make a point. It’s also not feminist because it occludes the men who were killed based on the same lies.

I am incredibly here to celebrate all the people who identify as witches now, and I think their spiritual and religious practices are very valid. However, whatever is happening with all this merch isn’t doing that. It’s trading in lies and profiting from pain. If we want to argue that our society is better now than it was in the early-modern period, then we need to start acting like it, and we need to stop repeating these falsehoods. Now.

Make a cutesy little shirt about that.