How the once-booming mine town of Picher, Oklahoma became America's most toxic ghost town

A once-thriving Oklahoma town is now known as one of America's "most toxic ghost towns."

The town structures that weren't demolished, destroyed by fire or a tornado, or collapsed are abandoned and dilapidated. A gorilla statue memorializing the town's 1994 football championship overlooks an empty parking lot.

But the population of Picher, Oklahoma, slowly dwindled over the last several decades to now empty.

So how did this happen?

Where is Picher, Oklahoma?

Picher is found in far northeast Oklahoma, on the border of Oklahoma and Kansas.

Part of Ottawa County, the nearest communities that aren't also ghost towns are Commerce, Quapaw and Miami.

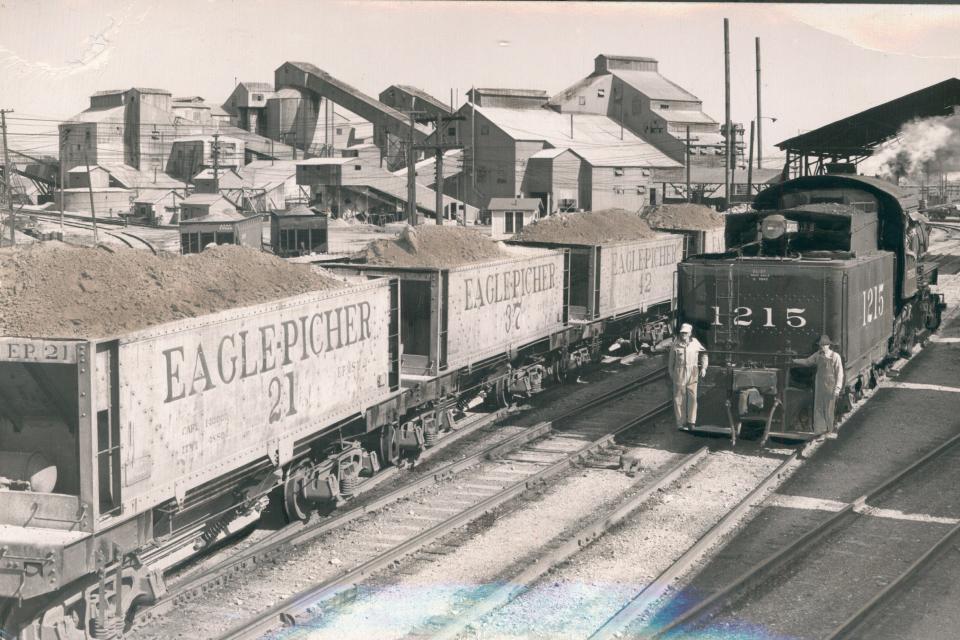

The town developed in late 1913 around the lead and zinc ore found in the area.

It was named for O. S. Picher, owner of the Picher Lead Company. Picher became incorporated in March 1918, and in 1920, there was a population of 9,726.

How did Picher, Oklahoma, become the "most toxic ghost town"?

Picher was part of the Tri-State Lead and Zinc District, which consisted of Oklahoma, Kansas and Missouri. It had the most productive mining field in the district, according to the Oklahoma Historical Society, producing more than $20 billion in ore from 1917 to 1947.

Over half of the lead and zinc used in World War I came from Picher.

The miners retrieving the lead and zinc ore — during the mining boom, more than 14,000 men worked in the mines of the Picher Field alone — were far more prone to silicosis, tuberculosis, lung cancer and liver failure than the average person, The Oklahoman reported.

Picher, Oklahoma deemed uninhabitable after decades of mining

But over time, as the lead and zinc mining byproduct piles of chat began to loom over the town, and even after the mining stopped in the 1960s, it was the younger generations who fell in the most danger.

Exposure to lead can cause children "damage to the brain and nervous system, slowed growth and development, learning and behavior problems, and hearing and speech problems," according to the CDC.

Not knowing the dangers of lead, families would let their children ride bikes over the chat piles, play in it and even use it in their sandboxes.

Picher is part of the Environmental Protection Agency's Tar Creek Superfund Site — named as such because the area came to the attention of the state government and the EPA in 1979 when water started flowing from underground mines and into Tar Creek.

Much of the downstream plant and animal life in Tar Creek were killed off as a result. The EPA became concerned about the acid water contaminating the area's groundwater and soil.

Millions was poured into trying to clean up the Tar Creek site, including the town of Picher. But it wasn't enough.

Mandatory evacuation of Picher, Oklahoma

A 2006 federal study showed 159 homes, businesses and public buildings in Picher were in danger of caving in due to significant undermining, according to The Oklahoman.

Thirty-five cave-ins had occurred in the area since a 1982 inventory by the Oklahoma Geological Survey, the report stated.

With this new evidence, US Sen. Jim Inhofe called for a buyout for all residents willing to move to get out of harm's way. More than 200 families relocated over the next two years thanks to money from the federal government.

Then, in 2008 an EF-4 tornado leveled the southern half of the town, leaving seven dead and many more injured. The disaster accelerated the exodus of the town's remaining residents, though The Oklahoman reported in 2008 that some residents felt their buyout price wasn't enough to start over somewhere new.

Picher, Oklahoma becomes a ghost town

The federal buyout process was completed and the town ceased municipal operations in 2009, but not all Picher residents agreed to leave. In 2010, there were 20 within the boundaries of the former town, the US Census counted.

Gary Linderman kept his Ole' Miners Pharmacy running for years, telling The Oklahoman in 2008 he wouldn't close until someone made him.

Linderman called himself "the last man standing," until his death in 2015 lead to the closing of his pharmacy and the town with no one left.

This article originally appeared on Oklahoman: How Picher, Oklahoma became America's most toxic ghost town