Milwaukee's rivers were once open sewers to Lake Michigan. Here's how they're being cleaned up.

Milwaukee’s rivers went downhill fast after the height of European and early American settlement in the 1830s. For years the rivers were treated as open sewers and dumping grounds, leaving scars that are visible to this day.

People had turned their backs on the waters that brought them here, said John Gurda, Milwaukee historian and author of "Milwaukee: A City Built on Water."

But while there is a long history of problems, there's also a long history of progress.

Here are some of the biggest strides Milwaukee made in cleaning up its waterways during the last century.

More: Milwaukee loves its rivers and Lake Michigan — and keeps abusing them, too

In the 1920s, a Polish fishing village becomes home to sewage treatment plant

Before the city had a method to collect and treat wastewater, Milwaukeeans dumped raw sewage into the three rivers, Gurda said. The sewage flowed out to Lake Michigan, where it was diluted and then pumped right back into people's homes and businesses.

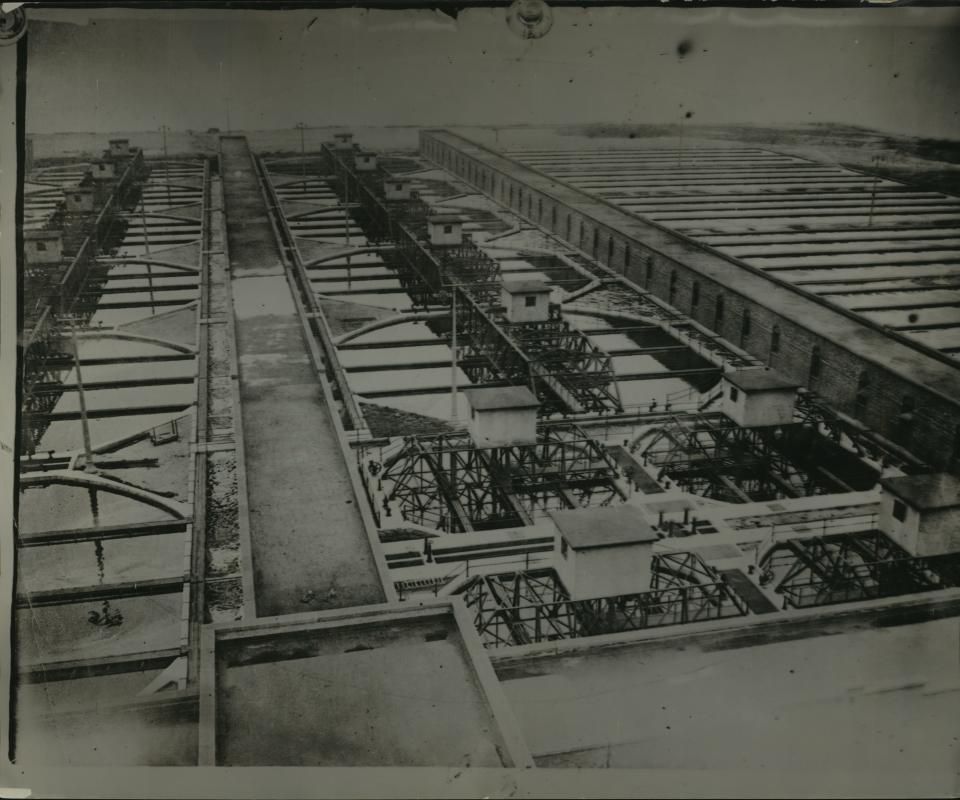

Jones Island, once home to a village of Kashubian fisherfolk, became home to the city’s sewage treatment plant in 1925. The plant used a new system to treat wastewater called the activated sludge method. The landmark system removed 95% of the bacteria from the city’s sewage and 90% of the solids.

At the time, the city had the largest activated sludge plant in the world. And the system helped bring money to the city when the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District started turning the collected biosolids into Milorganite, a fertilizer, one year later.

The city made another major stride after it opened the Linnwood Avenue water purification plant at 3000 N. Lincoln Ave., along the shores of Lake Michigan. Today the picturesque water plant is one of two water treatment plants that serve Milwaukee.

The sewage treatment and water purification plants became lakeside symbols of the city’s redefined relationship with water.

The Clean Water Act in 1972 made way for the deep tunnels

Across the country, people started waking up to the importance of freshwater after Lake Erie’s Cuyahoga River caught fire for a 13th time in 1969. A year later, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency was born, and Americans celebrated the first Earth Day thanks to Wisconsin’s own Gaylord Nelson. In 1972, the Clean Water Act was passed, regardless of former President Richard Nixon’s veto.

After the water act passed, people realized they had an obligation to clean up the city's waterways, Gurda said.

In the 1970s, lawsuits were filed under the Clean Water Act by Illinois, Michigan and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, arguing that sewage overflows were illegally polluting Lake Michigan. In response, the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District started work on the deep tunnels, an underground system designed to store raw sewage and storm runoff until treated.

Construction on the tunnels began in 1981 and the system was up and running in the fall of 1993, months after the city faced a cryptosporidium outbreak, the U.S.’s largest outbreak of waterborne illness to this day.

Before the deep tunnels, the Milwaukee region averaged 60 sewage overflows into Lake Michigan a year. Now, it averages about two, and the sewerage district collects and treats more than 98% of all wastewater.

A regional effort to clean up industrial pollution in the Great Lakes started in 1972

Once the city turned the corner on its sewage problems, it had new ones to face from industry.

In 1972, the U.S. and Canada signed the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement, which provided a framework for both countries to work together to restore and protect the Great Lakes. An update to the agreement in 1987 identified 43 areas of concern throughout the Great Lakes basin.

Areas of concern are former industrial sites stricken with problems from legacy pollution. The Milwaukee River Estuary, which includes the lower reaches of the Milwaukee, Kinnickinnic and Menomonee rivers, is one such place.

More: Milwaukee is turning around one of the most degraded sites in the Great Lakes. Here's how.

For generations, the rivers were dumping grounds for machine shops, tanneries, gas plants and breweries. These actions left behind pollutants like polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, which are a class of chemicals that are hazardous to humans, fish and wildlife at very low levels. PCBs settled into riverbeds and are still there, even though they were banned by the federal government nearly a half century ago.

Federal government funding has played a big role in cleaning up Milwaukee’s waterways, helping communities revitalize the waterfront with new businesses, real estate and recreational opportunities.

The Great Lakes Legacy Act, which was first authorized in 2002, directed funding to clean up the areas of concern. And in 2010, the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative, helped fast-track these cleanup efforts. The 2022 bipartisan infrastructure law gave a billion-dollar boost to the program to speed up the restoration of the remaining areas of concern in the U.S. by 2030. Of which, Milwaukee is receiving $450 million.

Projects have already started to dredge contaminated sediment, restore habitats and build fish passages so fish can swim freely through the rivers.

The sewerage district is leading a project to build a new facility on Jones Island to store the contaminated sediment. Construction of the facility is slated to begin next spring.

When it comes to these cleanup efforts, “there is a lot of hope and a lot of positive energy,” Gurda said.

The EPA estimates that the restoration and remediation projects in Milwaukee's area of concern will be completed between 2027 and 2030, once again charting a new course for the city's waterways.

More: A new fish passage around Kletzsch Dam will help restore Milwaukee's waterways. Here's how.

More: How restoration of a Menomonee Valley canal for kayaking will also preserve industrial use

Caitlin Looby is a Report for America corps member who writes about the environment and the Great Lakes. Reach her at clooby@gannett.com or follow her on X @caitlooby.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Three biggest strides Milwaukee made in cleaning its rivers