Once an outpost, Palm Desert celebrates 50 years as a city, with more growth on the way

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Marian Henderson was exploring the Coachella Valley long before the city of Palm Desert came to exist, visiting the desert with her brother to hunt rattlesnakes in the 1930s, with little idea of the impact she and her husband would later have on the area.

Soon after, Henderson — then still Marian Marsh — began acting in early Hollywood films such as “Svengali” and “Beauty and the Boss,” drawing praise in the film industry. Even with her rising star, she always chose the desert of Palm Springs for her three-week vacations granted by the studios.

Despite her frequent visits, Marian didn’t become a full-time valley resident until 1960, when she married Cliff Henderson, who developed the Palm Desert area with his brother Randall and others after World War II. Years later, she recalled her first time seeing the area — and not thinking much of it.

“It was really barren,” Henderson said in a 1980 interview with the Historical Society of Palm Desert. “Aside from the trees on El Paseo and the trees around Shadow Mountain and later at Firecliff, there wasn’t anything here.”

“It had a long way to go, I thought,” she added. “But it certainly did it in a hurry.”

Henderson, who became an outspoken conservationist and was known as “Mrs. Palm Desert” until her death in 2006, was among the many people who paved the way for the city that exists today, though her late husband, Cliff, is often credited as the key leader. While the area has long been home for the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians, Palm Desert’s development into a golf resort destination occurred in the last 75 years.

Now celebrating its 50th anniversary of incorporation, Palm Desert has largely developed into the city envisioned by its early promoters like the Hendersons — and it’s continuing to grow. With the city expected to add thousands of new residents in the coming years, local officials hope to maintain its reputation as a growing hub in the center of the Coachella Valley.

From an ‘acorn’ into a city

While the city is celebrating its 50th birthday, the land where Palm Desert sits today was long traversed by the Agua Caliente tribe, using a trail that would roughly become Highway 74 today to live seasonally in the mountains and on the desert floor.

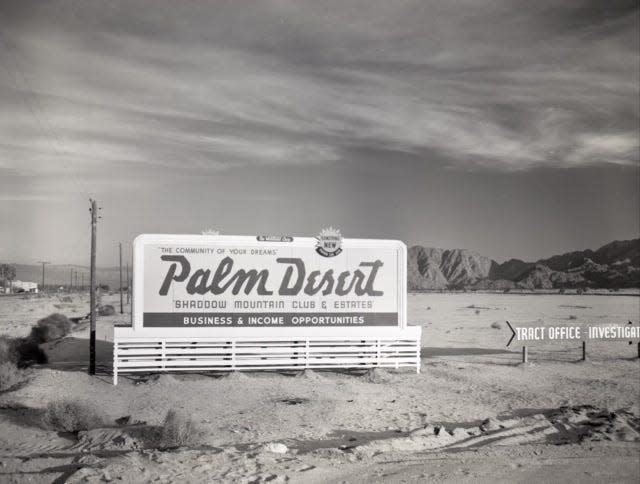

First identified as “Sand Hole” on maps, the land that would become Palm Desert gradually saw white settlers move into the valley, with the first homesteads established in the early 1900s.

An early outpost known as Palm Village got off the ground in the years after World War I, though it wouldn’t last long. The property was used as a military vehicle pool during World War II, while nearby land, including the Deep Canyon area, was used for the Army’s Desert Training Center. The camp extended south into the mountain cove of Deep Canyon, where tanks were given test runs in the rocky terrain.

The postwar years were when the Palm Desert community came into its own, in large part due to Cliff and Randall Henderson. Both were accomplished: Randall, the artist of the two, published the well-known “Desert Magazine," while Cliff, an aviation expert, had already started the National Air Races and developed the Pan-Pacific Auditorium in Los Angeles before coming to the valley.

After World War II, Cliff was interested in establishing a community somewhere new, with Randall suggesting the Coachella Valley as an ideal spot. Cliff bought several parcels of land south of Highway 111, slowly amassing over 1,600 acres for development.

Cliff formed the Palm Desert Corporation in 1945, with investors including radio personality Edgar Bergen, Leonard Firestone of Firestone Tires and movie-star Harold Lloyd. Along with Randall, he enlisted his other brothers Phil and Carl, along with their brother-in-law, landscape architect Tommy Tomson, to help carry out his vision.

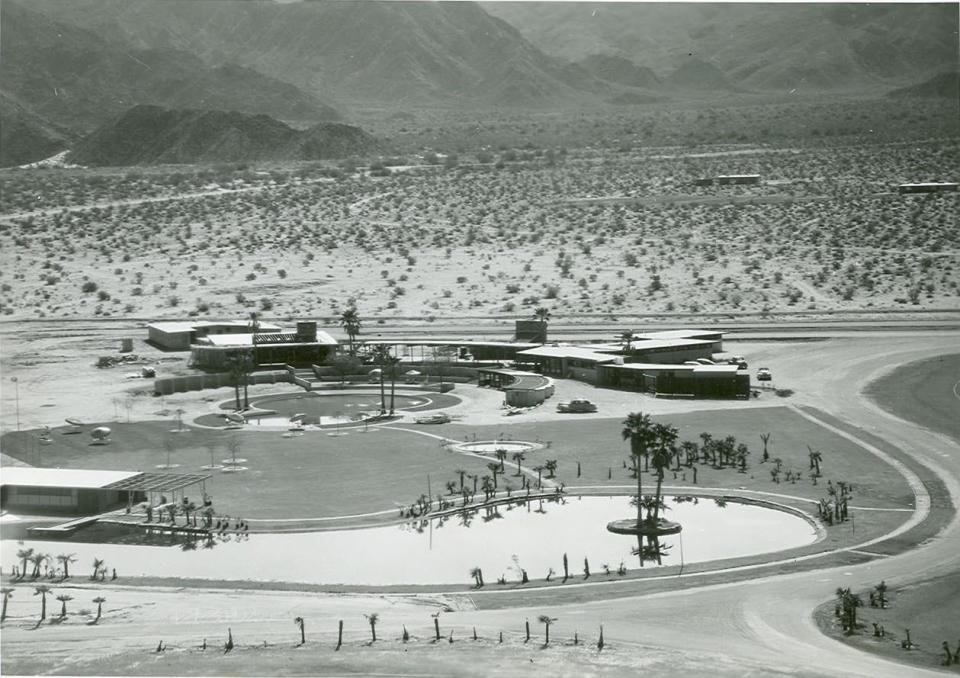

Their team then developed Shadow Mountain Club, a midcentury-modern clubhouse with a massive figure-eight swimming pool that opened in 1948. Rochelle McCune, an archivist with the Historical Society of Palm Desert, said the club offered “a built-in social world” for new families, allowing the surrounding neighborhood to take off.

“They had bands and these big dinner parties every Friday, and they had tons and tons of themed events,” McCune said.

The club was exclusive in its early years — “it was mostly you had to be rich and white,” McCune said — with celebrities such as Jimmy Stewart and Loretta Young among its frequent visitors.

The community paved the way for the city that would follow it: In an interview years later with the local historical society, Cliff Henderson said Shadow Mountain Club was the “acorn from which the whole community grew and developed.”

As the initial community grew, discussions within the local chamber of commerce and board of realtors about incorporating the community ebbed and flowed in the 1950s and 1960s, with opponents saying the move would lead to higher taxes.

But the push for local control eventually won out, in part due to ongoing tensions with Riverside County over new housing developments.

In 1972, a year before corporation, a group known as Concerned Citizens of Palm Desert was opposing seven developments approved by the county in court, contesting the projects’ density and heights. Some of the projects, such as a condominium complex on the west side of Highway 74 and a few mobile home parks, were ultimately built, leaving some residents upset.

Concerned Citizens of Palm Desert, the Palm Desert Property Owners Association and the chamber of commerce collaborated to form the city’s incorporation committee, gathering support from property owners after a few unsuccessful prior attempts. Roughly 76% of voters backed incorporation, and the city officially formed Nov. 26, 1973.

Early challenges, steady growth

In its early years as a city, Palm Desert’s population was small: Its first mayor, Hank Clark, said the city had an estimated 8,500 residents in 1973, while other estimates were higher. Regardless, its population climbed steadily over the next 25 years.

The city faced some challenges soon after its incorporation. In 1976, Tropical Storm Kathleen brought several inches of rain to the area, destroying many homes. Much of it was caused by a wall of water that swept across a large swath of the city when two dikes gave way, as “scores of homes were filled by several feet of mud,” according to past reporting by The Desert Sun.

How would the city respond after the calamitous storm? That answer was largely left to Carlos Ortega, who was hired as the assistant city manager a year the storm. In a recent interview, his widow, Rosemary Ortega, recalled her husband getting his first assignment: working on the flood channels that were overrun by the storm.

“The Army Corps of Engineers told the city that it would take 10 to 15 years to get this done, and the council at the time thought we can't wait that long. Who knows when it'll happen again?” Rosemary said. “So the city took it upon itself to start this project, and my husband was given the task.”

City officials collaborated with the Coachella Valley Water District and Indian Wells to build a 6-mile channel from the Santa Rosa Mountains to the Whitewater River channel within the next few years. The efforts have largely paid off, including during Tropical Storm Hilary earlier this year, though one local neighborhood near Interstate 10 still saw substantial flooding.

Soon after working on the channel, Carlos was made the executive director of the city’s redevelopment agency, essentially taking the reins on a wide range of new projects. Rosemary, who was raising their two daughters while teaching at College of the Desert, said her husband was “really big” on developing a wide range of affordable and senior housing.

The 1980s and 1990s were a period of considerable growth in Palm Desert. The city’s population more than tripled between 1980 and 2000, rising to 41,155 residents by the turn of the century.

The citywide number of homes also doubled, from 9,426 to 19,194, during that 20-year period. Rosemary recalled the city often converting land for apartment housing, such as The Regent and One Quail Place, during that timespan.

Carlos, who was promoted to city manager in 2000, was later honored for his focus on housing, following his death in 2009. Several years later, the city celebrated the completion of the Carlos Ortega Villas, an affordable senior housing complex that includes 72 apartments.

"He was a modest man. He probably would have said, 'No need to do that,'" Rosemary Ortega said of the complex being named after him. "We appreciate that the council chose to."

Environmental pioneer

The 1990s in particular saw the city pursue new initiatives focused on conservation and local transit. One morning, Carlos told Rosemary to “put on your tennis shoes” and join her for a stroll through what would soon become Desert Willow Golf Resort. As leader of the city’s redevelopment agency, Carlos led the charge to purchase the land, with Rosemary describing the project as “his baby.”

Desert Willow’s two courses, the first of which opened in 1997, helped spread the city’s conservation-focused reputation. The courses largely deployed desert landscaping, rather than thirstier plants and trees, and they also used recycled wastewater.

While other local courses, such as the Palm Desert Country Club, already used recycled water, the combination of initiatives landed Desert Willow on the cover of Smithsonian Magazine in 1997.

Mayor Kathleen Kelly, whose father Dick Kelly was a longtime councilmember until his death in 2010, said the city has been a leader in environmental stewardship “before it was tops on everyone’s priority list.” In 1993, the city gained state approval to allow golf carts for local travel to schools, parks, businesses and shopping centers, becoming the first in California to do so.

Kelly’s father also long represented Palm Desert on the Riverside County Transportation Commission, playing a key role in the 1988 passage of Measure A, a half-cent sales tax increase used to fund road and transit projects across the county.

Palm Desert’s efforts at the county and state level, as well as its active participation in the Coachella Valley Association of Governments, are part of what Kelly describes as the city’s collaborative nature in the mid-valley. The mayor also noted the 70-acre Civic Center Park, built in the 1980s, was made larger than needed to serve as a regional resource.

“Some of our sister cities have waxed and waned in their support of regionalism,” Kelly said. “Palm Desert has consistently recognized that you have to be reached at the regional table to get your share of resources, and has also realized that many of our issues — air quality, public safety, water conservation, mosquitoes — don't respect city boundaries.”

New housing, higher education among future keys

While the city saw substantial growth in the initial decades after its incorporation, its population has continued to tick up in recent years — and local officials expect a new wave of housing in north Palm Desert to soon bring thousands of additional residents into the city.

The growth is coming to an area where city officials have focused on two sites for developing the valley’s higher educational opportunities: the Cal State University-San Bernardino’s Palm Desert campus and the University of California-Riverside’s Palm Desert center.

Elected officials across the valley, particularly in Palm Desert, have long said a standalone campus, or “Cal State Palm Desert,” would give greater access to higher education to historically under-represented low-income and first-generation students.

There have been some recent signs of progress toward the city’s long-term goal of getting a four-year university in Palm Desert. For most of its existence, the infrastructure for CSUSB’s Palm Desert campus was funded solely by local government and philanthropy efforts — but that changed last year, when the state legislature committed $79 million for a new student center on campus.

Even with the new facility coming in the next few years, Kelly said it will be “immensely” challenging to get the four-year campus approved. However, she noted a recent study that found the Palm Desert campus would serve underrepresented and low-income students better than other proposed sites for CSUSB expansion.

“We have so many youth who can't or prefer not to leave the area ... But politics play a big part and, of course, the state of the state's finances,” Kelly said, adding: “We'll stick with it ‘til it gets accomplished.”

Meanwhile, plenty of new development is arriving in the area surrounding the two campuses, largely south of Interstate 10 and north of Frank Sinatra Drive. The number of homes in that area is set to more than triple in the area in the coming years, with more than 4,500 units either under construction or approved by the city.

More: Almost 5,000 new homes are coming to north Palm Desert. Can it handle them?

City officials estimate Palm Desert will add approximately 10,000 residents once the wide-ranging plans for new housing are completed. That would bring the city’s population over 60,000, nearly three times what it was as recently as 1990.

While residents have largely cheered the new developments, there are some lingering concerns. Watching the city grow, Rosemary Ortega said she worries about Palm Desert maintaining its present level of services and amenities with the new housing that’s been approved.

While some of the new housing will be specifically for people with low incomes, she also worried about the area’s affordability. A report from the Coachella Valley Economic Partnership found that 86% of the city’s workforce came from another city in the valley as of 2018.

“Because these homes are going at the prices that they are, that leaves a lot of people not being able to afford to live in the city where they work and provide services,” Ortega said.

Ortega also said the city’s main streets are “flooded” with traffic nowadays, adding: “We don’t want another Orange County.”

“A lot of people are moving here because we're a beautiful valley, and I'm proud of our valley,” Rosemary said. “But I would say controlled growth, responsible growth is what I would love to see.”

City officials are pursuing some initiatives aimed at improving local transit, with a particular focus on making Palm Desert the location of a mid-valley rail station amid regional plans to start regular passenger service between the Coachella Valley and the L.A. area.

“It's certainly my goal on council to retain the ease of living that attracted so many people to our desert, while still accommodating essential growth,” Kelly said.

Now with a population of roughly 51,500, the city has come a long way from the barren landscape that Marian Henderson encountered over a half-century ago.

Tom Coulter covers the cities of Palm Desert, La Quinta, Rancho Mirage and Indian Wells. Reach him at thomas.coulter@desertsun.com.

This article originally appeared on Palm Springs Desert Sun: Palm Desert still booming as it celebrates 50th anniversary as a city