What once were safe havens for those fleeing China now feel dangerous

ISTANBUL — A Uyghur Muslim rights activist who tried to escape oppression by fleeing his homeland with his family says the tentacles of the Chinese state followed him to Turkey and then Morocco, where today he sits in a solitary jail cell.

Idris Hasan recalls how he used to pretend to be a donkey, carrying his children around on his back. But since his incarceration two years ago, the web designer can only blow kisses through the phone screen, a guard always by his side, as his family watch from their small, third-floor Istanbul apartment crammed with books and toys.

“I have a picture of my family, but I cannot look at it,” Hasan, 35, said in one of his thrice-weekly calls to his wife and three children from prison. “If I look at this picture, I get very upset and cry, so I put this picture under the blanket and never look at it.”

China did not respond to questions about why it is pursuing Hasan, who is also known as Yidiresi Aishan, the Chinese version of his name.

Chinese authorities have accused Hasan of being a member of the East Turkestan Islamic Movement, a group the U.S. once classified as a terrorist organization during a period of increased U.S.-Chinese cooperation on counterterrorism after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, but which it now says has been defunct for more than a decade. China contends the ETIM remains active.

Hasan’s family and human rights groups say he has merely helped Uyghurs in Turkey by translating and doing graphic design and worked for a diaspora newspaper documenting alleged abuses against his community back in China.

According to Amnesty International, Hasan is at “high risk of being extradited to China where he will face a real risk of arbitrary detention and torture.” He is a victim of what Western governments and activists describe as a vast, global network of surveillance, intimidation and persecution by the Chinese government, one that stretches far beyond its own heavily repressive borders and onto the soil of friendly and hostile nations alike.

One of those countries is Turkey, which for years was seen as a safe haven for Uyghurs fleeing Chinese repression. It shares religious, cultural and linguistic ties with this Turkic ethnic group and hosts its largest diaspora community of 45,000. But according to a new report by Spain-based human rights group Safeguard Defenders and shared exclusively for this article before publication, in recent years Turkey has been “losing its reputation as a safe haven” for Uyghurs as it “closely aligns itself with Beijing economically and politically.”

Many experts say this shift is motivated by Turkey, currently mired in financial crises, courting a greater influx of Chinese cash.

“China’s transnational repression of Uyghurs overseas has created a pervasive climate of fear,” said the report by Safeguard Defenders, which is focused on the Uyghur situation and other alleged human rights abuses by China. “Those targeted are not just human rights activists and advocates but also ordinary Uyghurs, including students and members of the business community.”

Like most Uyghurs, Hasan is originally from Xinjiang, a vast region in western China. According to an array of witness testimony and documentary evidence over the past decade, Chinese authorities are involved in an increasingly brutal crackdown against the Uyghurs in Xinjiang.

Confirmed data is scarce, but estimates by human rights watchdogs and other groups say China sent upward of 1 million people to internment camps, where many are cut off from family and physically and psychologically tortured. Separate investigations by Amnesty International and a tribunal of independent human rights lawyers have detailed evidence of detainees being raped and forcibly sterilized.

The U.S., like other Western governments, says this “campaign of repression against ethnic minorities” amounts to genocide. The United Nations Human Rights Office says China may be guilty of crimes against humanity.

China says it has closed the camps, although NBC News’ British partner, Sky News, found that many of the detainees were still incarcerated in regular prisons, some of which have been significantly expanded, and the region remained under a blanket surveillance and law enforcement regime.

China denies all of this, saying it sends Uyghurs to “vocational training camps” because of terrorist and separatist attacks since the 1990s. According to a 24-point rebuttal published by the Chinese state news agency Xinhua in 2021, “ethnic separatists, religious extremists, and violent terrorists” in Xinjiang “plotted and conducted several thousand violent terrorist acts” between 1990 and 1996.

“Xinjiang-related issues are not about human rights, ethnicity or religion, but about fighting violence, terrorism and separatism,” Liu Pengyu, spokesperson for the Chinese Embassy in Washington, said in an email in response to questions about the treatment of the Uyghur community.

Asked about the Turkey-based Chinese diaspora, he dismissed them as “a few overseas people” who had “fabricated lies” that were “refuted by their relatives and friends.”

“Residents in Xinjiang live a peaceful and happy life,” he added. “We hope that the parties concerned can respect the facts and truths about Xinjiang, let go of their preconceived prejudices, stop groundless smears and view Xinjiang and China under the principles of truthfulness, objectivity and fairness.”

For Yalkun Uluyol, pursuing truth, objectivity and fairness leads him to a different conclusion.

Originally from Xinjiang, the social sciences scholar says some 30 members of his family — including his father, whom he has not seen since 2018 — have at some point been detained by Chinese authorities. That led him to author the report published this week by Safeguard Defenders.

Uluyol surveyed 93 members of the diaspora in Turkey, 80% of whom said they have been unable to contact some family members back home since at least 2017. More than one-third said they had been harassed by Chinese police or state agents while in Turkey.

Uluyol found a common tactic is for Chinese authorities to threaten Uyghurs in Turkey by using their families back in Xinjiang. China’s aim, he said, is to stop them engaging in activism, recruit them to spread Chinese propaganda and to spy on other Uyghurs.

“In one of the stories that I was told, police talked to one Uyghur activist here in Istanbul and told him, ‘Your grandma says hi,’” Uluyol said.

“He didn’t provide what the police asked him to do” so they asked him “do you even care about your family?” Uluyol said.

Another person interviewed, Jevlan Shirmemmet, 32, a lawyer from Xinjiang, has been campaigning to find his mother, Suriye Tursun, a bookseller detained since 2018. One day, he said, he received a call from his father, brother and uncle back home — whom he believes were under pressure from Chinese police — telling him to keep quiet.

“I said, ‘Where are you? Where’s my mom?’” he said. His father responded, “‘What are you doing?’” and “‘You have to stop,’” Shirmemmet recalled. “My answer was: I won’t stop until my mom gets released.”

Hasan, the prisoner in Morocco, also believes his detention has come at the behest of China.

He and his family arrived in Istanbul in 2012 but he fled again after less than a decade having been arrested there four times. Turkish authorities have provided little details about why he was detained — not responding to detailed requests for comment for this article — but his family and human rights groups have no doubt that it was linked to his work in support of Uyghur rights.

He tried to get to Western Europe but, not realizing Beijing had issued an Interpol “red notice” for his arrest, he was detained en route in Morocco. Interpol canceled this in 2021, telling NBC News in a statement this week that it had done so after “new and relevant information” had come to light, without giving further details about the reason for the initial notice or its withdrawal.

Two U.N. bodies have urged Morocco not to deport him back to China, saying he faces possible torture and death. The Moroccan government did not respond to detailed questions about his case.

It’s unclear what’s next for Hasan and thousands of other Uyghurs who have fled China.

Turkey in the past welcomed in tens of thousands of Uyghurs, often turning a blind eye when their travel documents were incomplete or forged, said Gareth Jenkins, a veteran Turkey analyst who has lived in Istanbul for 30 years.

In 2009, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan went as far as to call China’s treatment of the Uyghurs a “genocide.”

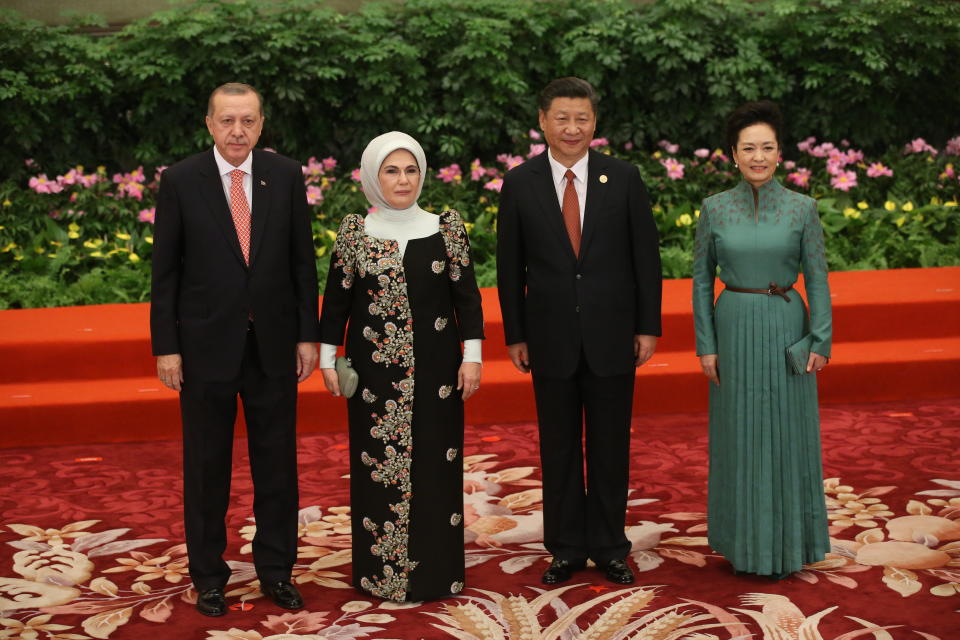

That began to change in 2016 when Turkey joined China’s Belt and Road Initiative, an unprecedented global infrastructure project that critics see as Beijing’s attempt to gain influence abroad and make smaller countries financially dependent on its investment.

The embodiment of this new Sino-Turkish era came in 2017 when they signed an extradition treaty that was ratified by China in 2020. While Turkey has not ratified the agreement, the fear of extradition is a constant worry “that hangs over” Turkey’s Uyghurs and puts them “in a very precarious situation,” said Lisel Hintz, an assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies in Washington.

“The Uyghurs began to come under pressure from the Turkish authorities,” which became far stricter on passports, residency permit renewals and other documentation, Jenkins said.

The human cost of this tightening can be found sprawled across the table of an Istanbul cafe; a few legal but ultimately worthless travel documents are all Gayret Erlibek has to his name. He was detained at Istanbul Airport after leaving Xinjiang via Kazakhstan in June, and still does not know his next move after being allowed to pass through.

“I thought: This is it, I’m going to die, they’re going to deport me to China,” he said.

There is one clear motive for Turkey’s apparent shift, according to Jenkins, Hintz and others: the promise of Chinese cash.

There have been plenty of investments so far: China’s partial construction of the world’s largest suspension bridge, the Canakkale Bridge, its majority ownership of the massive shipping container port at Kumport, and Chinese tech giant Alibaba buying the Turkish e-commerce firm Trendyol.

“There have been many investments promised, but not all of those have come through,” Hintz said. “And Turkey would like more.”

These geopolitical changes have very human consequences for people like Hasan. Morocco’s extradition treaty with China ratified in 2017 makes him especially vulnerable and dependent on international appeals to delay his extradition request.

While Turkey slowly becomes an uncertain haven for so many like him, Hasan’s fate now lies with Morocco.

From prison, he said that sometimes he cannot catch his breath.

“I am already two years in this prison, and nobody has said when I will get out,” he said.

“If they send me back to China, it is equal to death,” Hasan added. “I think my future is darkness; I don’t see any light.”

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com