How a one-armed former slave united Montgomery in the early 1900s

“I think that any man has a legal right to save anybody from drowning.”

These words from Bob Goodwyn ran in the Montgomery Advertiser in 1908, a time when few former slaves were quoted. His acts of heroism on Montgomery’s stretch of the Alabama River were recognized by whites and inspired Black people long before the Civil Rights Movement.

That wasn't always the case for Goodwyn. Before people called him a hero, many only saw him as an old, broken man. They knew Goodwyn as “Old Bob,” since he was likely in his late 50s or 60s. They also called him “One-armed Bob,” because years earlier his right arm had been ripped away and the skin flayed from his skull by gears at a gin shop.

He shouldn’t have survived the accident, at least not according to doctors at the time.

But Goodwyn found his way to a new path, working for Southern Railway official W.A. Henderson as a ferryman in Montgomery. Before the area's major bridges existed, Goodwyn was tasked with bringing people and vehicles safely across the Alabama River.

Though the stories of his life and death reached papers across the nation and were shared around the world, few remember Goodwyn today. That’s happened with stories of other heroic, groundbreaking Black people, something Montgomery historian Richard Bailey hopes will change.

“You have throughout Alabama history, pockets of incidents that went against the status quo,” Bailey said. “It’s just that they’ve not been elevated to the point that they are known by the general population.”

Goodwyn became a hero in Montgomery just under five years before the birth of Rosa Parks, and more than two decades before the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was born. Aside from mining operations that saw Blacks and whites working and striking together, Alabama's segregation was strong in 1908. Only 7 years earlier, the state outlawed interracial marriage, and made it mandatory for Black and white children to attend separate schools.

On Aug. 14-16, 1908, some 650 miles away from Montgomery, a mob of 5,000 whites in Springfield, Illinois, killed their Black neighbors, and burned Black-owned homes and businesses. It became known as the Springfield Massacre.

But 1908 and 1909 saw sparks of racial unity in Montgomery. Not acknowledgement of Black equality by whites, but at least a shared recognition of one Black man’s character, hard work and heroism — even if all of that came with a level of accepted racial separation. Goodwyn was often referred to as a “negro hero.” The word “negro” was inserted automatically next to anything to do with a person of color, especially in news published at the time by the Montgomery Advertiser.

A one-armed rescue in swift water

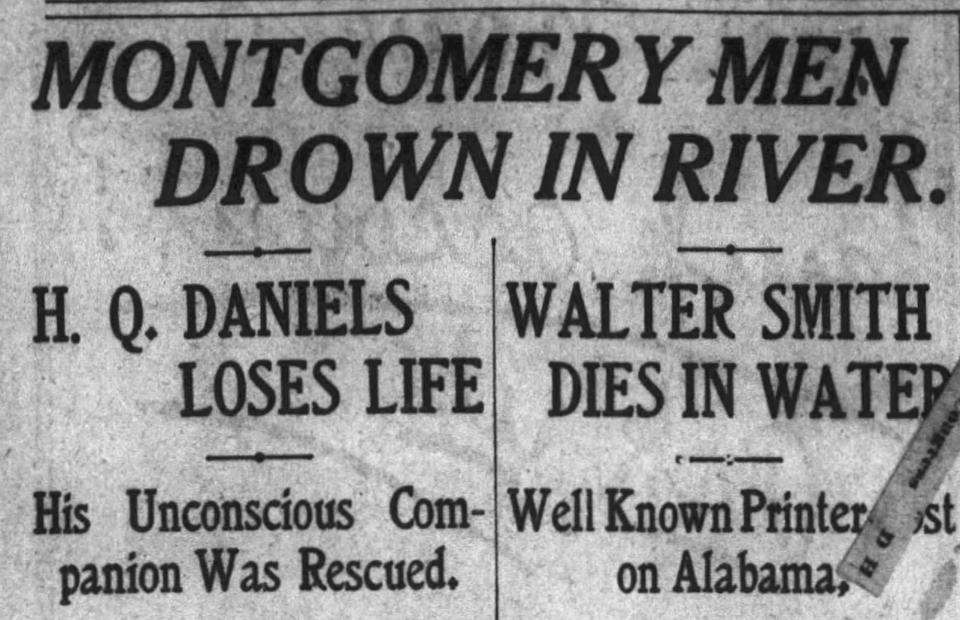

At around 6 p.m. on April 11, 1908, E.W. Bliss, a ticket purchase agent for L&N Railroad, and his friend and roommate H.Q. Daniels, a 16-year-old machinist for Western Railway, left work and decided to go for a boat ride on the Alabama River to get some exercise. By all accounts, they couldn’t have picked a worse day to get on the water. The river was swollen and swift.

The two white men had only just started paddling upriver in a small skiff when the ferry reached the Montgomery bank at the foot of Commerce Street. When Bliss and Daniels attempted to go around the ferry, their boat hit an eddy — a miniature whirlpool. It caused their small boat to spin and overturn in the fierce current, and the men were left clinging to their boat.

From atop the ferry, Goodwyn witnessed the accident and took his own small boat into the water to help them. Goodwyn was in the same swift waters, paddling as best he could with his left arm to attempt a rescue.

Before Goodwyn could help, Daniels was washed away and drowned. Bliss managed to stay above the surface just long enough for Goodwyn to grab him. He lifted the unconscious Bliss into his own boat and then one-arm paddled the two of them through the current to shore, where Bliss got medical treatment and survived.

A few days later, at the suggestion of a reader listed as Mrs. William Knox, the Advertiser began accepting donations for Goodwyn. People young and old donated, from students to former state treasurer George W. Ellis. The Advertiser wrote that funds “will be turned over to the gallant negro.”

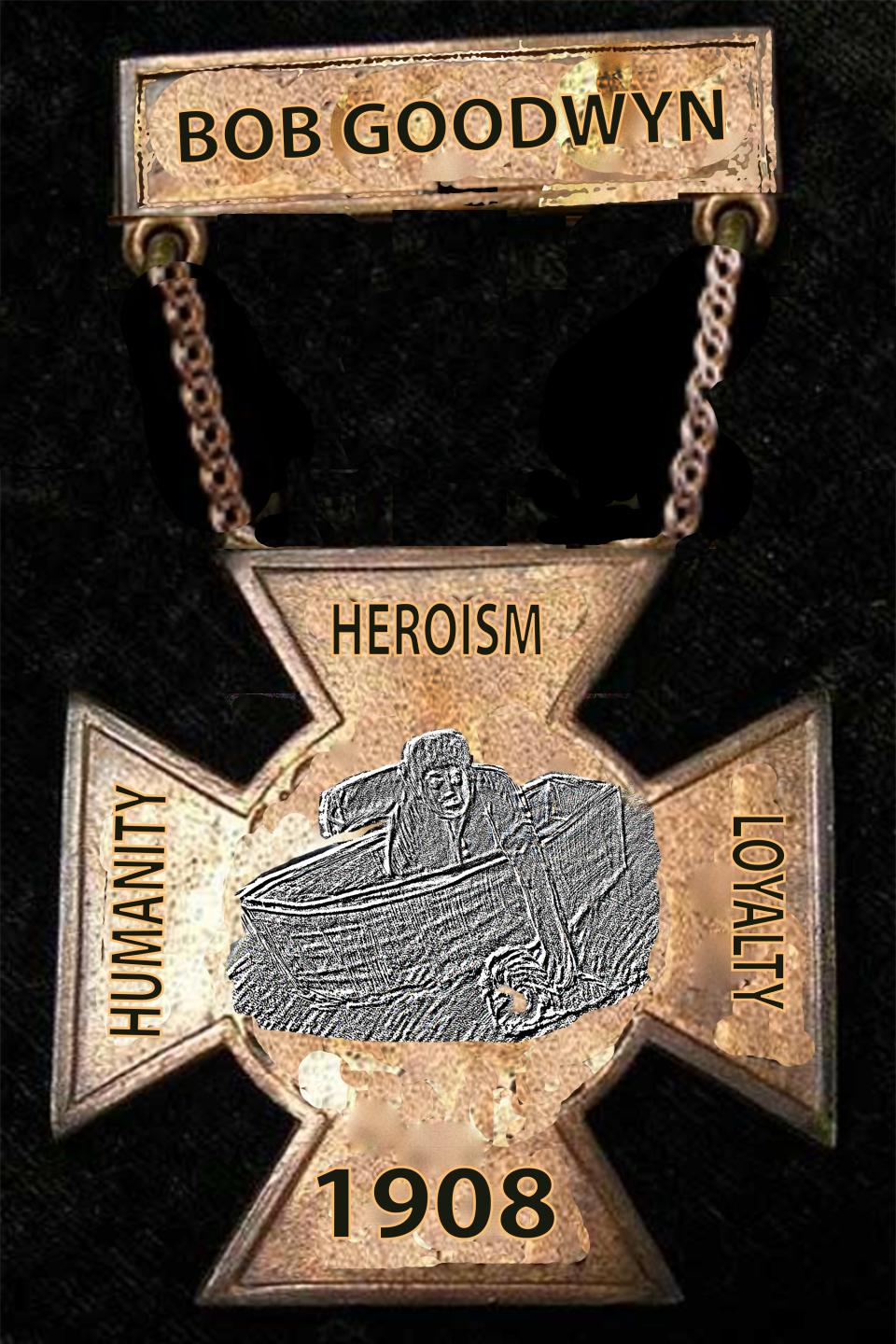

On May 30, 1908, Goodwyn was honored with a gold medal by Montgomery officials for his heroism. According to the Advertiser, local students raised funds for the medal. Mayor W.M. Teague pinned it to him in a ceremony held in the Montgomery City Council chamber. The mayor and Sheriff Horace Hood spoke to the crowd and called Goodwyn a worthy man. They spoke of the effort it took for a one-armed man to do such a rescue.

“What might he not have been able to do had he possessed two arms?” Teague said.

The sheriff, a former member of the state House of Representatives from 1898-1899, knew how to work a white Alabama crowd. Hood offered thanks on behalf of the entire community for Goodwyn’s bravery, though his wording left no doubt that even this new hero wasn’t accepted as an equal to whites.

“This medal is not only a reward for your individual act, but to assure all people of your race that they have the good will of the white people when they perform their duties, and show good will to the dominant race, and this good will, as you know, Bob, is not to be despised,” Sheriff Hood said. “Now, Bob, I hope that you will wear this badge ever remembering that wherever you may be it will be a protection and an honor to you.”

The medal had a gold bar into which Goodwyn’s name had been engraved. Two gold chains from it held a pendent that was a gold Maltese cross. On the arms of the cross were engraved “humanity," "heroism" and "loyalty.” On the bottom was engraved “1908.” In the center of the cross was an engraving that showed a one-armed man bending over the side of a boat in the act of rescuing a drowning man, whose head was just above the water.

Whether or not it was done on purpose, the medal’s description is very close to the Southern Cross of Honor, a commemorative medal that the United Daughters of the Confederacy established less than a decade earlier in 1899, used to honor Confederate veterans.

Speaking to everyone at the ceremony, Goodwyn said, “I have not done anything that I was not worthy to do. I think that any man has a legal right to save anybody from drowning. I want to thank you for what you have done for me. I hope you will all live a long and happy life as long as you live.”

The Alabama River claims Goodwyn

Sadly, Goodwyn’s life ended just under a year later, claimed by the same swollen and rushing waters from which he rescued Bliss.

Goodwyn, a Black man named Dick Johnson, a white man named Willie Dillard, 20, a white boy named Tom Harper who was Dillard’s cousin, and an unidentified white boy drowned in the Alabama River on March 9, 1909.

The five of them were crossing the river on a batteau, a flat-bottomed boat. Goodwyn and Johnson were trying to get to the ferry, which had been parked on the opposite bank from Montgomery. Dillard and the boys were going to look after another boat that was on the other side of the river.

As they approached the other bank, they ran over the ferry cable. The heavy wire rope had sagged and was below the surface of the swollen river. It caused the boat to capsize.

Witnesses watched helplessly from the Montgomery bank as Johnson, Dillard and Harper went under, and didn’t resurface. Goodwyn managed to get to the capsized boat and fought against the current to get to the other white boy, but the boy went under and disappeared.

Goodwyn clung to the overturned boat, which carried him downriver. A boat in Elmore County was put out to meet him, and a rope was thrown to Goodwyn. It was reported that to grab it, Goodwyn had to let go of his one-armed grip on the boat. The rope didn’t reach Goodwyn’s left hand, and he fell into the water. Witnesses said Goodwyn sank into a whirlpool and didn’t rise again.

Goodwyn’s body was recovered two weeks later when flooding subsided, some seven miles away from Montgomery. Though Goodwyn was in almost unrecognizable condition, his missing arm made for a quick identification.

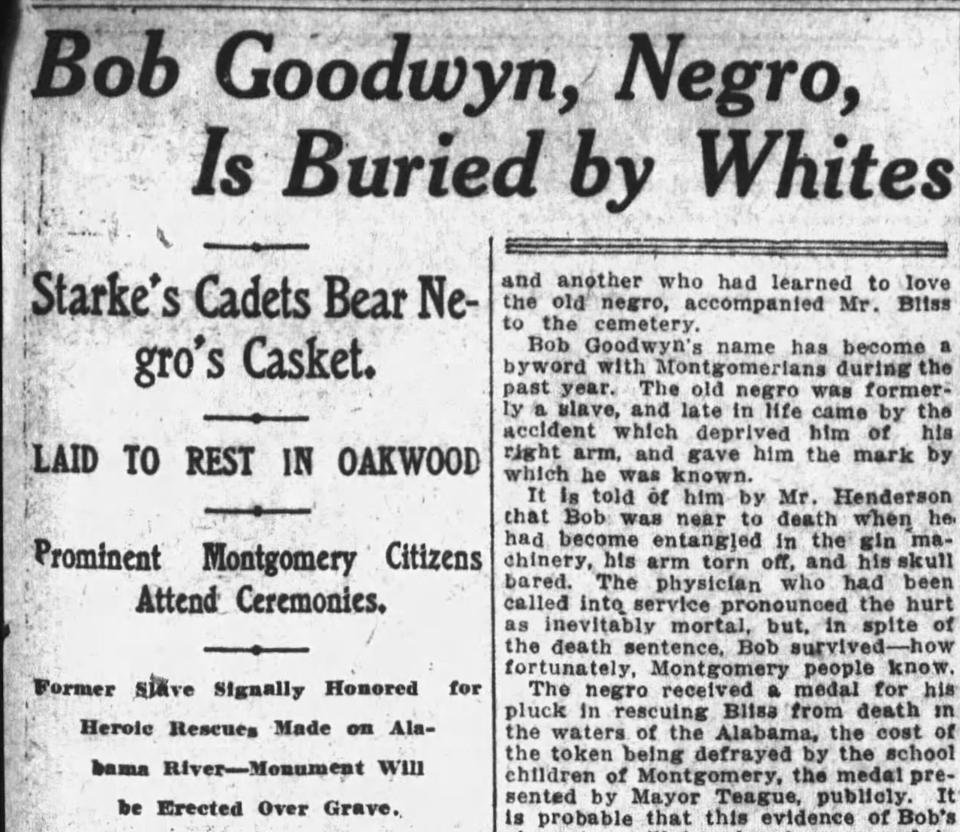

An integrated 1909 funeral in Montgomery

At first, Goodwyn was to be buried in Lincoln Park Cemetery, Montgomery’s negro burial ground. Bliss changed this by securing and paying for a lot in Oakwood Cemetery. The move also meant a change of funeral homes handling the body, from the Loveless’ establishment to Tice’s.

The 3 p.m. graveside funeral was held on March 28, 1909. The headline for the Advertiser’s story covering Goodwyn’s funeral read “Bob Goodwyn, Negro, is Buried by Whites.” Hundreds of Black and white residents attended.

The Advertiser wrote: “In his death, one-armed Bob Goodwyn, the negro ferryman, achieved a something as few of his race have done — for at his grave in Oakwood Cemetery yesterday, whites and blacks mingled with little distinction; the two people mingled their voices in the ‘Nearer My God to Thee’; both bowed to tender, revertant homage to one whom they hailed as a hero.”

More: 100-year-old fought in WWII then fought for civil rights in Montgomery

Eight young white boys from Starke’s School wore military uniforms as they carried Goodwyn’s casket. Services were conducted by R.C. Judkins, pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church.

Goodwyn’s grave was in a lot in front of the cemetery on the main drive “near which white men have been buried since Montgomery was a city,” the Advertiser wrote. His body was held in a plain vault. Plans began almost immediately to raise funds for a monument at the grave.

While there were no floral arrangements, many individuals came with flower bouquets. At least one girl picked flowers from a nearby bush and dropped them on the grave. Soon others were dropping their flowers in as well.

Goodwyn had no family present. His only known living relative was an elderly mother, believed to be in her 80s, who couldn’t leave home. According to Bailey, she lived in Madison Park, and it is likely that Goodwyn lived with her.

The location of Goodwyn's remains today is somewhere among a thousand or so graves, and efforts are underway at Oakwood to locate it. The exact spot isn't noted in the cemetery's records.

As for what happened to Goodwyn’s medal, that remains a mystery. Because he wasn’t buried with it, and accounts from 1909 said that his mother didn’t want it, the medal was presented to the Alabama Department of Archives and History. At the time, the department had only been open for eight years, and was housed in the state Capitol building.

While notations of its acceptance by the Archives exist, officials there said the medal couldn’t be found after a recent extensive search.

Montgomery Advertiser reporter Shannon Heupel can be reached at at sheupel@gannett.com

This article originally appeared on Montgomery Advertiser: In life and death, a one-armed Black hero united Montgomery in 1900s