One civil rights icon has been overlooked in history books. His family is trying to change that.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

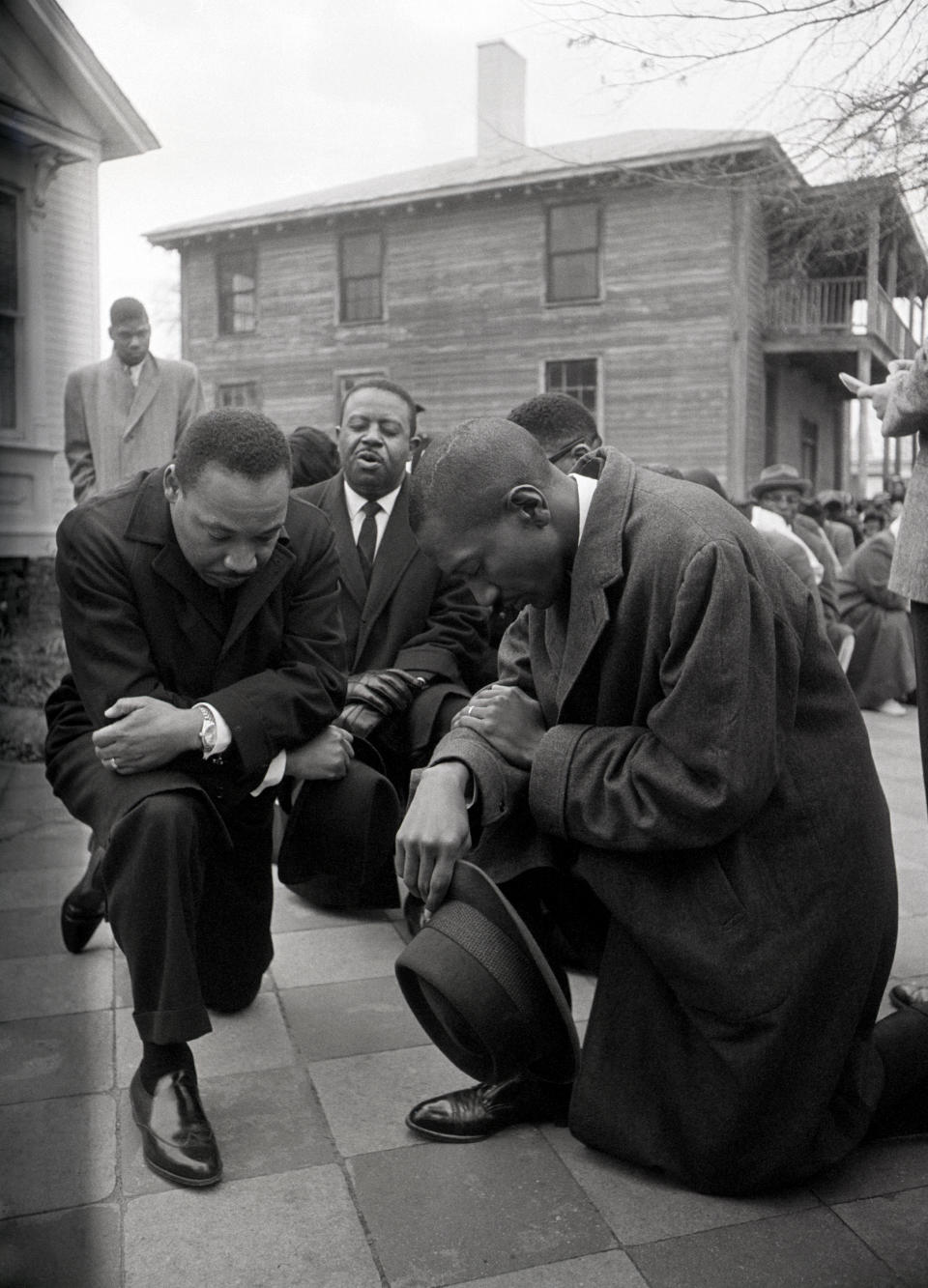

Alan Reese’s passion for protecting his grandfather’s place in history started when he was a fifth grader. Reese came across a picture of the Rev. Frederick Douglas Reese standing next to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in one of his history books. The only problem was that none of his classmates believed the man standing next to one of the most formidable figures in American history was his grandfather.

Little did the other students at Cedar Grove Elementary School in Ellenwood, Georgia, know that Reese’s grandfather, as an activist and a member of the clergy, was a key figure in the fight for civil rights, and had urged King to come to his hometown, Selma, Alabama, to march for the voting rights of Black people in 1965.

That’s why Alan said he needed to set the record straight. After he told his grandfather what had happened at school, Frederick Reese called Alan’s teacher to confirm the story, which turned into a surprise classroom visit.

“He walked in, and they went bananas, because his face was still the same,” recalled Alan Reese, now 37 and living in Atlanta. That moment, he said, “put a burn in me at a young age.”

Decades later, Alan Reese and his brother, Marvin are working to keep their grandfather’s name alive by organizing tours all over Selma, detailing who their grandfather was, his significance to the area and how his work helped create change for Black people in Selma and elsewhere in the country.

The brothers run the tours “every other weekend right now,” said Marvin Reese, 39. “When we first started it wasn’t as often but now it’s building up momentum.”

The F.D. Reese Historical Tour, named for their grandfather who died in 2018 at the age of 88, takes tourists and local residents of all ages and races to historic sites throughout Selma that played a significant role in Reese’s life — starting with his home. After taking groups through their grandfather’s home, the Reeses move on to R.B. Hudson High School, a former segregated school where Reese planned the Teacher’s March in 1965.

Frederick Reese, who was a graduate of Alabama State University and an educator for more than 50 years, said in a 2004 interview that Black teachers in Selma “did not really understand the influence they had in the community as an organization” he said. This was why he believed they made such perfect activists in the civil rights movement.

The next destination is Clark Elementary School, where Reese led more than 100 teachers to the Dallas County Courthouse. There, Reese and other teachers peacefully protested for the right of Black citizens to vote.

“There were deputies across the door with their billy clubs, with their guns,” Reese said. “And the vicious sheriff, Jim Clark — who at that time was a symbol of resistance in the South — and he gave the orders for us to get off of those steps, that we were making a mockery of his courthouse. And we reminded him that that courthouse also belonged to us.”

Reese was president of the Dallas County Voters League, a “particularly instrumental” organization in seeking to register Black voters in Selma before the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965, said Adam Green, an associate professor of American history at the University of Chicago.

“It’s important that we find ways to raise up the story of Dr. Reese and others and convey a sense that their personal stories are the stories of the history of the civil rights movement, and what they risked,” Green said. “And what they put on the line is something that needs to be commemorated in the same sort of way that we commemorate members of the military and first responders today within the United States, because they built and defended the country, as surely as anybody who took up arms does.”

After visiting the courthouse, the Reeses’ tour continues to the Brown Chapel AME. Church, where marchers prepared for what became known as Bloody Sunday in which police officers attacked and beat more than 600 protesters marching across the Edmund Pettus Bridge. The bridge, named after a state Ku Klux Klan leader and where the Reeses conclude their tour, became one of the most important landmarks of the civil rights movement. While the tour is designed to last an hour and a half, the Reeses said it often goes longer — up to three hours — because participants have so many questions.

“They always say, ‘Wow,’” Alan Reese said, “Like, ‘why haven’t I heard of this man?’”

Leaders like King or politician and civil rights activist John Lewis, who served in the U.S. House for 33 years, have become symbols of the movement, “rather than thinking about people that were organizers, and people who exemplified things that moved members of the community,” Green said. Over time, Green said, contributions from people like Reese have simply faded from memory.

To counter that, the Reeses strive to get their grandfather’s name widely known and honored. Alan Reese said he encouraged his grandfather to write his autobiography, “Selma’s Self Sacrifice,” which was published one year after his death. The Reeses have also visited schools in Selma and across the nation to teach students about Reese and his work. They also hold weekly discussions on a program called “The Lineage Podcast,” where they “fill in certain holes of the civil rights movement.”

Reminders of Reese are sprinkled throughout Selma, including the Frederick D. Reese Parkway and F.D. Reese Street. The city also commemorates Reese every March during F.D. Reese Day. Now, Alan and Marvin Reese hope to get a school named in his honor and are working on a documentary about their grandfather.

And with all the work that they’re doing, the Reeses say they know their grandfather would be proud.

“I always say that I feel honored to even be connected to a part of history that a lot of people are yearning for,” Marvin Reese said. “And they have an appetite for it.”

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com