What one company's ventilator work says about our chances to outpace coronavirus

EATON, Ohio – At a family-owned manufacturing company on the western edge of the state, the indoor pickleball courts, normally a staff favorite during breaks, are empty because of social distancing, and everyone has their temperature taken when they arrive for their shifts.

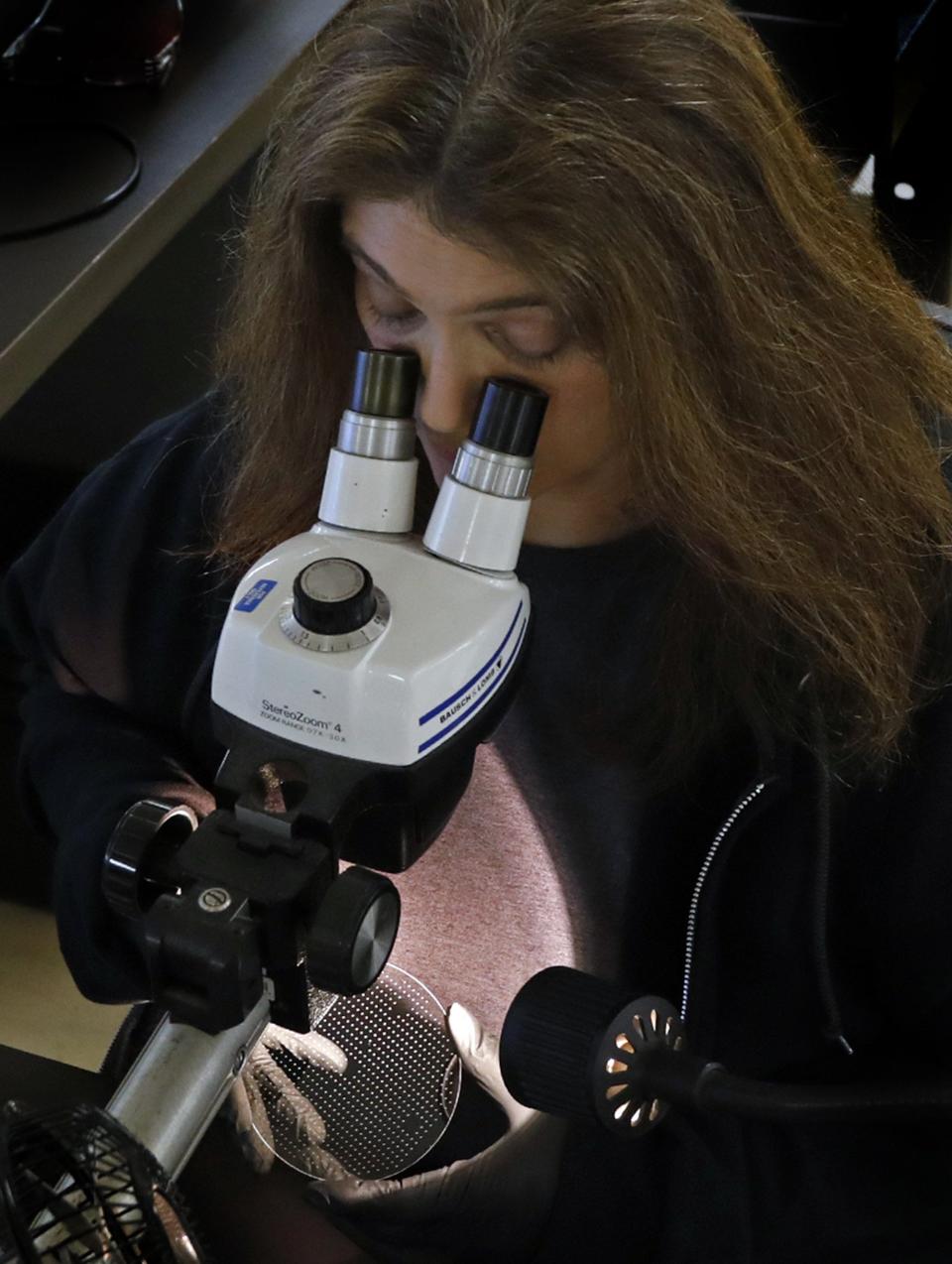

Bullen Ultrasonics, a 140-employee machining business, is running full-steam. The company is essential to the nation's effort to build more ventilators, even if what it does is drill holes in small pieces of glass.

The manufacturer offers a look into the lengthy supply chain to produce ventilators that help COVID-19 patients breathe when their lungs struggle to do so on their own.

The lifesaving devices made at one ventilator company, Medtronics, require the coordination of more than 100 suppliers. The suppliers are in 14 different countries – including places struggling to respond to coronavirus themselves.

Bullen plans to cut down the time it takes to make its next batch of glass constraint wafers from eight weeks to less than two weeks to meet demand from two unnamed customers that make pressure sensors, a key part of ventilators.

Bullen has to make its own tools. The workers then use the tools to cut tiny holes in special glass with sound waves. That’s all before shipping out the product for future steps in the ventilator-manufacturing process.

“We’re hoping to be able to start machining these parts April 2 and start sending them to our first critical customer,” Bullen President Tim Beatty said.

That’s about two weeks before New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo anticipates a peak in coronavirus cases in that state and a month before public health officials expect a peak in Ohio. New York called for 30,000 ventilators to meet a surge in coronavirus patients.

Ventilators have computer-like monitors situated on top of them. They have buttons and dials to customize the settings for each patient. They require plastic tubes of different sizes to hook up to the patient. Each machine needs electrical parts to plug into the wall. Some machines have handles. The devices are usually on four wheels, so medical providers can move them around like carts.

From Utah to Sweden, at least nine ventilator manufacturers – including GE Medical, Philips Respironics and Medtronic – said they are ramping up production to respond to the crisis. Government officials talked of bringing Ford, Tesla, and General Motors into the production effort.

“Medtronic recognizes the demand for ventilators in this environment has far outstripped supply,” Bob White, a vice president for Medtronic, said in a statement. “No single company will be able to fill the current demands of global health care systems.”

A spokesman for Medtronic described a fivefold increase in production of ventilators in a matter of months. In a normal week, the company can make 100 ventilators. The company increased to 225 per week and intends to make more than 500 per week in the weeks to come. That will require a fivefold increase in supplies.

Nicholas Petruzzi, a professor of supply chain management at Penn State University, said most manufacturers have eliminated any excess capacity in their plants as part of a decade of trying to control their costs. That means a backlog is inevitable when demand spikes.

Beatty said Bullen is fortunate. He saw a potential shortage of glass coming a few months ago and built up an inventory. Without it, he said, the glass he sources from Germany and Japan could take months to acquire.

“The U.S. government has come to our customers and said, ‘We need you to ramp up production. Anything you have we’ll take,’ ” Beatty said. “In order to do that, they need to come to somebody like us."

In New York, Cuomo criticized the government’s production-based approach because he said the car companies won’t be able to make ventilators fast enough for his state, which is the hardest-hit in the nation.

He wants the federal government to step in and send ventilators to his region, then move the supplies and medical personnel elsewhere when demand weakens in New York. He described the approach in a news conference Tuesday.

“If we get past the apex, we get over that curve. That curve starts to come down, we get to a level where we can handle it, I’ll send ventilators,” Cuomo said. “I’ll send health care workers. I’ll send our professionals, who dealt with it and who know, all around the country. And that’s how this should be done.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Factory scrambles to supply ventilator makers for coronavirus victims