One exhibition, 62 Picassos: Visit the museum for 'Picasso on Paper' this winter

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This winter, visitors have a special opportunity to visit the museum and see an exciting exhibition, “Picasso on Paper: The Artist as Printmaker, 1923–72,” right here in Hagerstown. The exhibition continues through March 3.

The first exhibition at the museum to focus on Spanish artist Pablo Picasso’s work since 1972, “Picasso on Paper” features 62 etchings, engravings, lithographs and linocuts created by this renowned modern master.

Although Picasso is best known as a painter, he also was a prolific and diligent printmaker, producing more than 2,400 prints during his career.

“We are not merely the executors of our work," he once remarked, "we live our work.”

This exhibition, which coincides with the 50th anniversary of Picasso’s death in 1973, takes us on a journey through the artist’s graphic work, allowing us to see his innovative techniques and enjoy a range of fascinating subjects.

A painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramist and theater designer, Picasso did not employ just one style. Instead, he enjoyed shifting between and combining abstraction and classicism. As you make your way through the show, you will see how eclectic he was in this regard.

Picasso was immersed in representing his inner personal world, one that is filled with depictions of the women in his life, bullfights, scenes inspired by the ancient Greco-Roman world, his studio, and dialogues with Old Master artists who preceded him.

Over the decades, Picasso worked in many print studios, collaborating closely with their owners and workshop assistants. Among those printers were Roger Lacourière, Fernand Mourlot, Hidalgo Arnéra, and Aldo and Peter Crommelynck, with whom he mastered techniques such as etching, lithography and linocut. In fact, Mourlot recalled Picasso’s passion for the printmaking process itself. “He loved the printing works, the noise of the machines, the smell of the ink, the contact with the workers,” Mourlot said.

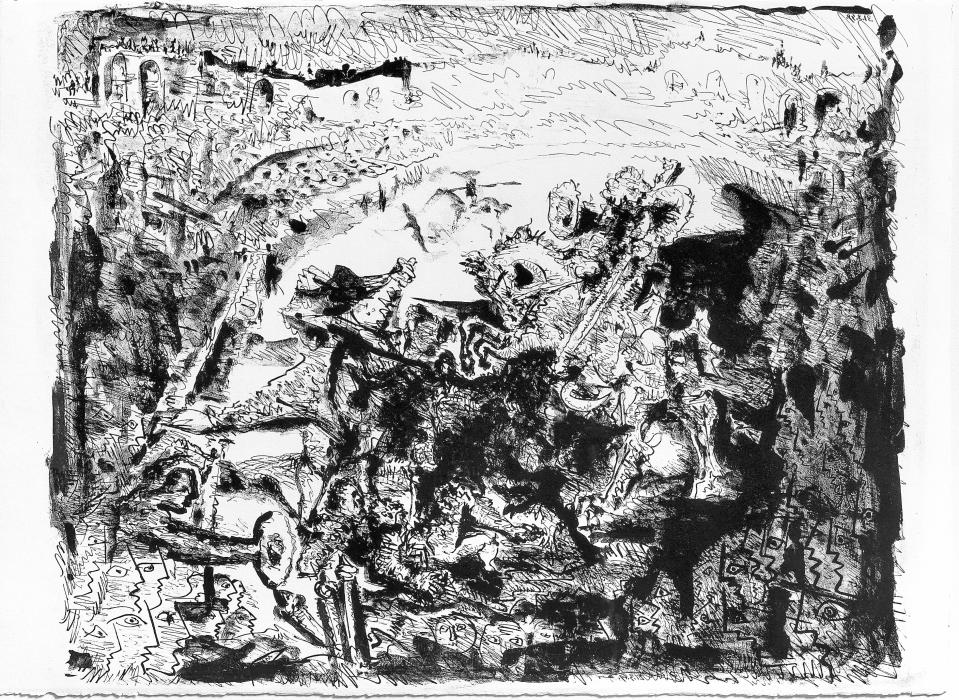

As part of his Spanish heritage, Picasso held a lifelong fascination for bullfights, which began in his childhood when he attended the spectacles with his father. His interest in bullfights accelerated during the 1930s and '40s with lithographs such as “La Grande Corrida III (The Large Bullfight)” from 1949, which shows entangled figures and animals in an arena (note the arches on the upper left and right).

Stylistically, the work borders on near complete abstraction through Picasso’s use of frenzied, highly gestural etched and brushed lines. His innovative technique establishes an atmosphere of tremendous energy, excitement, and violence that one would experience at a bullfight.

In the center of this print, we observe a bull, its head turned downward, charging toward a picador (bullfighter riding on horseback) thrusting his lance at the animal. On the ground behind him is a matador carrying a cape, who chases the animal to the right. Around the edges of the print are spectators, tightly packed together in the stands, who eagerly watch; including one figure preparing to throw a hat into the bullring. Here, controlled and ragged lines are strongly juxtaposed and chiaroscuro (contrast between light and dark areas) abounds.

In a much calmer subject, 1957's “Buste de Profil (Profile Bust)," Picasso portrayed his second wife, Jacqueline Roque, the only partner he allowed to watch him work in his studio. Shown looking to her right in contemplation, Roque’s face appears to be illuminated by a beam of light while her hair and the background are cast in shadow. Her large right eye draws us into the composition with her intense gaze, immediately capturing our attention.

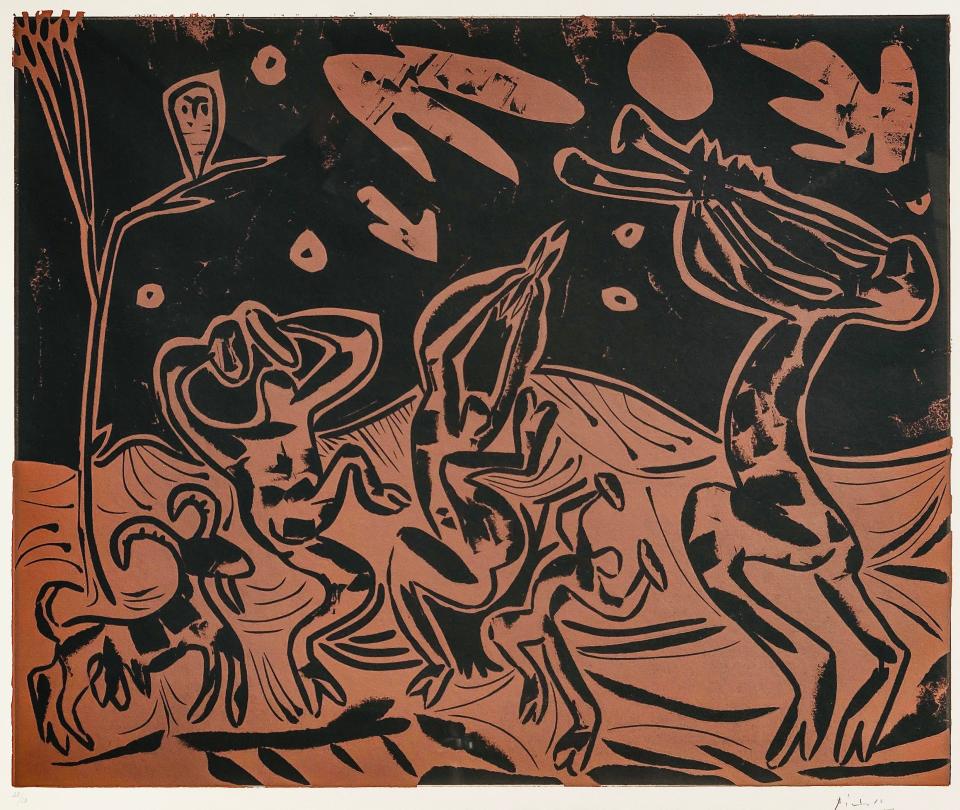

Among the outstanding linocuts in the exhibition is “Nocturnal Dance with an Owl” (1959). In the 1940s and ‘50s, ancient themes reemerged in Picasso’s linocuts. “It is strange, in Paris I never draw fauns, centaurs, or mythical heroes … they always seem to live in these parts,” Picasso once recalled, referring to southern France, where he lived at the time.

Indeed, these creatures emerge in his lively, joyful scene, which represents a bacchanale (a Greco-Roman celebration in honor of Bacchus, god of wine). Perched on a branch on the left side of the image, an owl looks down at reveling fauns — one playing the pipes, others dancing. Using black and brown ink, Picasso heightened the drama and excitement of the scene while accentuating the silhouettes of the characters.

While “Picasso on Paper” is on view, be sure not to miss the museum’s very own Picasso prints that are also on display — “Large Female Nude” (1962) and “Alex Maguy” (1962) — along with other works by his colleagues, including Cézanne, Matisse, Braque, and Fernand Léger. Since these are works on paper, subject to damage from light exposure, they are only displayed for a limited time.

Daniel Fulco, Ph.D., is the Agnita M. Stine Schreiber Curator at the Washington County Museum of Fine Arts. The museum is open Tuesday through Friday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.; Saturday, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. and Sunday, 1 to 5 p.m., closed Mondays and most holidays, including New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day. Go to www.wcmfa.org or call 301-739-5727. Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and LinkedIn.

We're getting to the end of the year — a good time to reflect on what museums are for

This article originally appeared on The Herald-Mail: 'Picasso on Paper' exhibition on view until March