One family's desperate act to escape overcrowded housing in L.A.

At first, Ruby Gordillo thought she was lucky.

After six months of sleeping on friends’ and relatives' couches with her husband and three children, Gordillo in 2014 found a place for her family in Westlake, a neighborhood on the western border of downtown.

Her elation didn't last long.

Immediately, Gordillo was confronted with the reality of five people stuffed into a 350-square-foot studio in one of the most overcrowded neighborhoods in the United States.

Gordillo and her husband set up a queen mattress for themselves and a triple-decker bunk bed, an arm’s length away, for the children. The two-story, century-old Period Revival building housed 20 families squeezed so close together that Gordillo could hear whenever her neighbors used the bathroom.

The apartment was rife with roaches and bed bugs. Gordillo’s youngest daughter became covered in welts from insect bites. They threw out mattresses and furniture.

The stress of living this way only mounted when Gordillo heard what sounded like a sexual assault in the alley and prohibited her children from playing outside.

“Those are the things that people don’t think of when they think of Los Angeles,” said Gordillo, 35. “They think of shopping and whatever. But for the people that live here, it’s our lives. It’s survival of the fittest.”

In Westlake, 36% of homes are overcrowded, meeting the federal definition of having more than one person per room, according to a Times analysis. It’s the second-most-crowded community in L.A. County, behind neighboring Pico-Union, and nearly 11 times the national rate.

Gordillo’s family was paying $800 a month for the studio. Her husband earned little as a cashier, so the family saw no way out. But that only made Gordillo's determination to improve their situation grow.

“We were shoulder to shoulder, losing our minds every day,” she said.

Gordillo joined a group that advocates for low-income renters. In spring 2020, on the eve of the COVID-19 pandemic hitting Los Angeles, she took the only step she could think of to escape her overcrowded apartment.

Gordillo's family and a dozen others seized empty, state-owned homes in El Sereno that had been left abandoned for an aborted freeway project. Preparing for the desperate act terrified her. Because her husband is living in the country without legal permission, Gordillo signed paperwork for her brother to take guardianship of her children in case she got arrested and lost custody.

During Gordillo’s first few nights occupying a house in El Sereno, California Highway Patrol officers used megaphones on their squad cars to call on the families to come out. Private security guards shined flashlights through the windows.

But after weeks of protests and appeals to the governor and other elected officials, Gordillo’s family was allowed to stay in the Eastside neighborhood.

Instead of apartment buildings overflowing with people, El Sereno is filled with bungalows. The neighborhood's overcrowding rate is half that of Westlake.

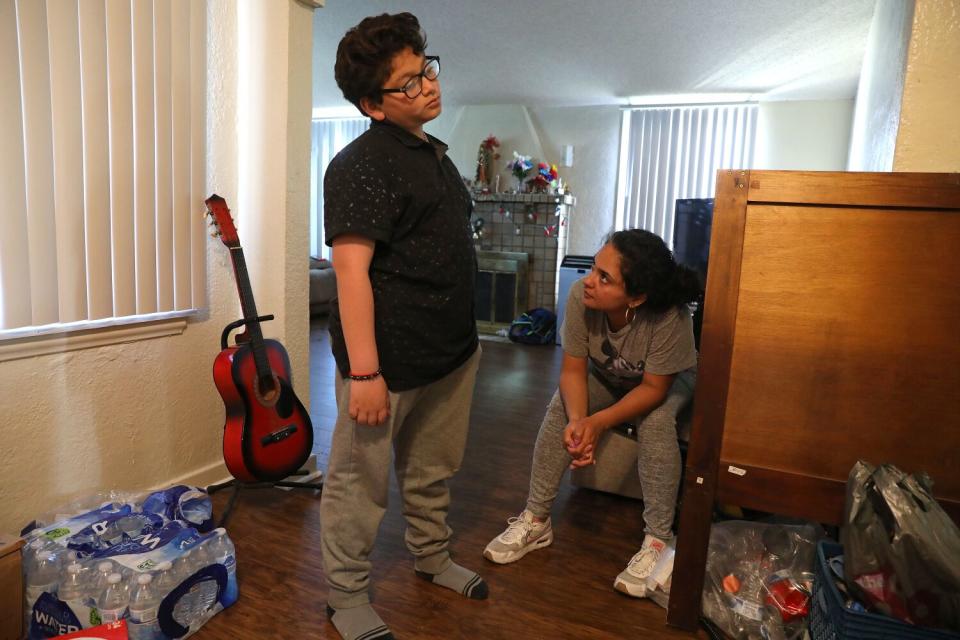

Gordillo's family lives in a publicly owned, three-bedroom, beige, stucco home on a quiet street, for which they pay $200 a month. She and her husband have a bedroom. Her daughters, 16 and 14, share another. Her 11-year-old son has his own.

In the pandemic’s first year, when classes were held remotely, her children were able to take their school-district-issued Chromebooks and spread out in the home. Finding somewhere to eat no longer conflicted with finding somewhere to do homework.

She’s certain her children have received a better education because they have been able to study without distraction. They've all enrolled in neighborhood schools.

In Westlake, Gordillo never lit candles, because she feared her whole apartment complex would catch fire. The El Sereno home has enough space to set up two altars with votive candles for the Virgen de Guadalupe.

Sometimes, Gordillo sunbathes in the backyard by the tangerine tree and listens to the mockingbirds.

This summer, she signed up for adult school to complete the few classes she needed for her high school diploma.

"That's something that I wanted and tried to do so many times and had to keep putting on the back burner," Gordillo said. "I'm excited that me and my kid would be graduating together."

But Gordillo's time in El Sereno may be coming to an end.

Next month, the family is supposed to leave their home, because the state allowed them to sign only a short-term lease.

Gordillo doesn't know where they're going to live next.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.