He’s one of Granite City’s most well-known residents. Now his name is on a street.

Granite City has more than 27,000 residents, but only one came to mind when Mayor Mike Parkinson found out that he had the opportunity to name a street after someone.

It was Babe Champion.

The 90-year-old is a community activist and volunteer, a retired teacher, coach and referee, and a self-described “smart aleck” who loves to tell stories and make people laugh.

“He’s one of the kindest and most sincere human beings you could ever meet, and he loves Granite City more than anything,” said resident Theresa Werner.

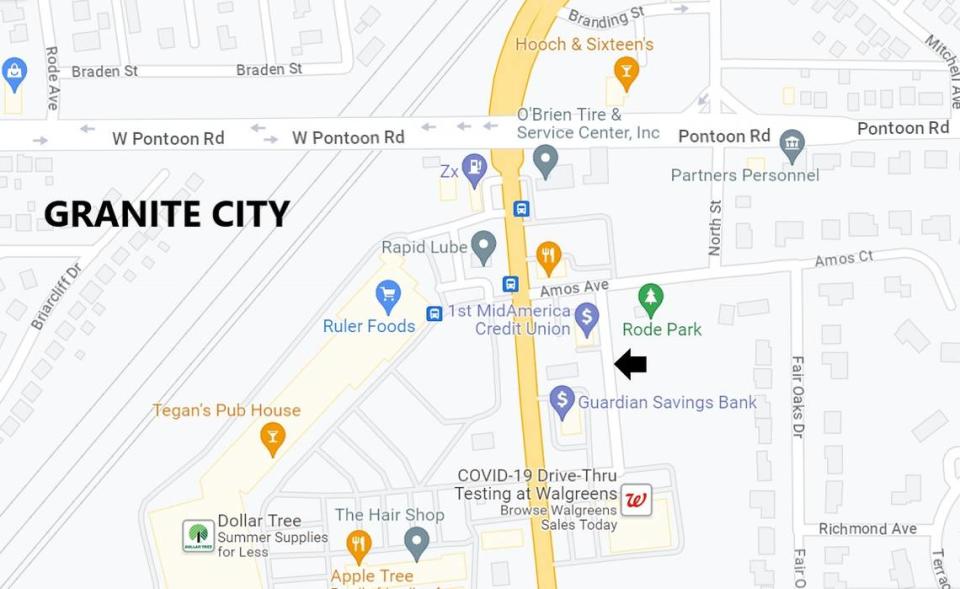

Werner was one of about 150 people who showed up at Rode Park for the dedication of Babe Champion Parkway on Friday. She held a sign that read, “Granite City loves Babe Champion.”

Retired teacher Teresa Johnson recalled some of Champion’s many causes, including a fundraising campaign to get lights installed on the Granite City High School football field 23 years ago.

“He’s just done so much,” she said.

Also on Friday, Parkinson proclaimed June 9 as Babe Champion Day in Granite City and gave Champion a key to the city.

Street along Rode Park

Babe Champion Parkway is about two blocks long. It runs along Rode Park, between Manley Avenue and Amos Court, behind First MidAmerica Credit Union and Guardian Savings Bank.

The Granite City engineering department recently brought it to the mayor’s attention that the street had never been named.

Parkinson told the crowd at the dedication ceremony that Champion’s door was one of the first he knocked on when running for mayor in 2021 because he knew his support was key.

“Everywhere he goes, he brings smiles to people’s faces,” Parkinson said. “Every athlete who has come up in this community, he’s been there sitting in the stands, rooting them on.

“He’s raised his family here. He’s a pillar of the community. He’s a bright spot even on the darkest day. Any time you see Babe, he’s got a smile on his face, and he has something good to say about something. His stories are legendary. He’s just the face of Granite City. He’s the ambassador of Granite City.”

Madison County Coroner Steve Nonn also spoke at the dedication ceremony, and Madison County Sheriff Jeff Connor was one of several law-enforcement officers in attendance.

“I’m from Granite City, and I’ve known Babe for many years,” Connor said. “He’s a great man. His last name fits his personality. He’s a champion.”

Named after Babe Ruth

Champion has been known as “Babe” so long, many people don’t realize that his real name is Conrad. He thinks his father, a baseball enthusiast, nicknamed him after New York Yankees slugger Babe Ruth.

Champion was a sophomore on the Granite City High School varsity baseball team that won the state championship in 1948.

“We played New Athens and won 4-1, and Whitey Herzog was on the (New Athens) team, and he went on to play pro baseball, and he coached the Cardinals,” Champion said.

Champion nearly died twice before graduating from high school. He spent 26 days in the hospital with pneumonia at age 15 and missed his entire senior year due to tuberculosis.

Champion considered his nine months at the Madison County Tuberculosis Sanitarium a stroke of luck because he graduated a year late and met his future wife, Odessa “Sue” Weston, at his commencement in 1951.

Champion went on to play baseball at Shurtleff College in Alton.

“I said, ‘Coach, I can’t make the Friday night game. I’m getting married. But I’ll be there Saturday for the double-header.’ That was our honeymoon,” he told the crowd at the dedication ceremony.

Champion spent nearly 35 years teaching physical education and health and coaching baseball, including 27 years at Granite City High School, before retiring in 1989. He also refereed college football and basketball games.

Champion has been inducted in the Granite City Sports Hall of Fame, the Illinois Basketball Coaches Association Hall of Fame and the Greater St. Louis Amateur Baseball Hall of Fame.

Champion names as his mentor the late Lawrence “Mr. Mac” McCauley, a teacher, coach and Granite City High School principal, who gave him his first coaching opportunity.

“I always talk about three things that are important to live by: Say thank you, be accountable and create opportunities,” he said.

Inaugural Hall of Famer

Champion was one of the inaugural inductees in the Granite City Sports Hall of Fame in 1987. He credits founders Al Barnes, Frank Kraus and Bill Schooley for inspiring much of his community activism.

In 2010, Champion was instrumental in reviving the Hall of Fame after 10 years of dormancy with help from Gus Lignoul and Bobby Galvan.

Champion has long promoted the idea that a movie should be made about the Eastern European immigrants on the Granite City High School boys basketball team who overcame big challenges to win the state championship in 1940.

Also on Champion’s bucket list is placing an electronic sign in front of the high school to let residents know about game schedules and other activities; a Wilson Park stadium for college women’s fast-pitch softball and youth programs; and a new football and soccer field house.

“The old one was built in 1959, and it needs to be torn down,” he said.

Champion and his wife had four children. Their daughter, Robin, died at 41 from complications of foot surgery.

Son Keith is a scout for the San Francisco Giants. Son Kirk recently retired after coaching college baseball for 10 years and working in player development for the Chicago White Sox for 34 years. Son Brett is a retired executive for a nonprofit association.

Sue Champion died in 2019 after 66 years of marriage. The family assumes it was due to a heart attack, according to Babe Champion.

“She died at 9:52 in the evening, and her last words were, ‘Don’t quit,’ and since that time, I’ve been going a mile a minute,” he said.