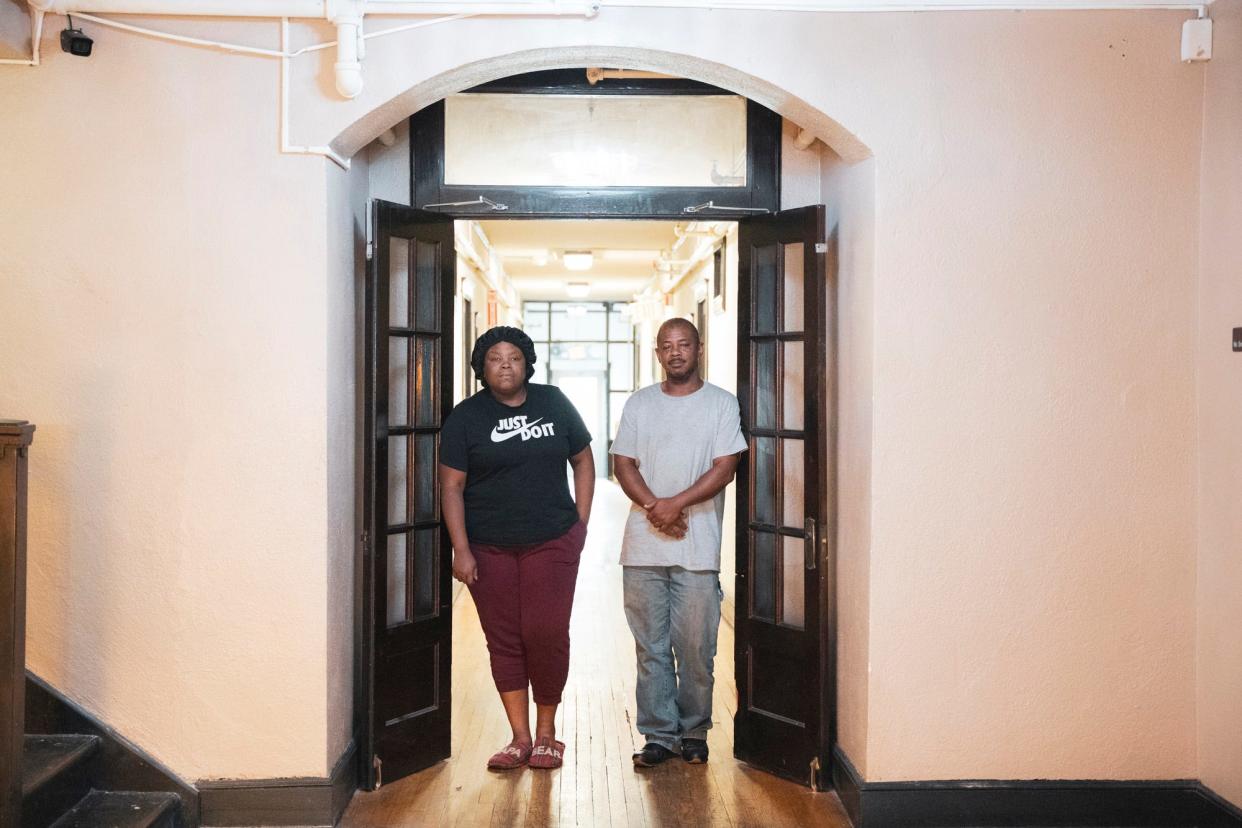

One Memphis couple's journey: Stuck between a home and homelessness

Walking from her SUV to her hotel room after treatments, Katherine Harris could barely put one foot in front of the other.

Though she’d raised three kids, she’d never felt so tired. The chemotherapy that was crushing her cancer was also shattering her.

She yearned for rest, but it was often elusive. She heard folks hollering and children running in the rooms and hallways around her. And the worries inside her head were even louder. Would one of these strangers pass a virus to her already feeble body?

“I really just want to get in an (apartment),” the 43-year-old said. “I can’t be compromised right now.”

While receiving treatment for breast cancer in the summer and fall of 2022, Harris and her husband, Fred Scott, bounced back and forth between a pair of southeast Memphis hotels. Apartment managers had refused to rent to them since she filed for bankruptcy in 2020.

The couple’s journey is an increasingly common one in Memphis and the rest of the U.S. The country’s housing shortage is pushing a growing number of renters to dwell in hotels, despite the fact that few would choose to. And in Shelby County, bankruptcies play a major role in who ends up living at properties built for travelers.

Once there, renters are subject to the whims of the hotel’s management. They have little protection against immediate evictions or drastic rate hikes.

In Memphis, a room at an extended-stay hotel — which includes a kitchenette — rented for an average of $93 per night in 2022, 23% higher than in 2017, according to research from The Highland Group. For most of last year, Harris and Scott spent between $1,300 and $2,100 per month in a city where the average one-bedroom apartment still rents for about $950 per month.

Even before these recent price jumps, long-term residents spent far more on their stays than they would have on apartments. According to a 2019 study, about 85% of extended-stay hotel residents in Georgia used more than the recommended 30% of their income for housing, and 25% used more than 80% of their income.

These costs make it extremely difficult for people such as Harris and Scott to save up for a deposit on an apartment.

“These people … don’t have any chance to get a decent place to live,” said Alejandra Cadiz, a nonprofit worker who helps longtime hotel residents in Georgia find apartments. “They are paying a higher rate, and they are not building credit. … It’s a circle that’s very hard to get out of.”

Harris was more direct.

“(It’s) a trap.”

A scarlet 'B'

In 2020, when health officials around the globe were asking residents to stay at home, Harris was having major issues with hers.

At her rental home in Westwood, the pipes were leaking, creating mold, she said. And the floorboards were rising, allowing bugs to crawl in.

Never afraid to advocate for herself, Harris filed a complaint with code enforcement. And then she made what housing experts say is a big mistake: She stopped paying rent. When tenants don’t pay rent because of poor maintenance, landlords can easily file for eviction. And that’s just what Harris’ landlord did in July 2020.Through research, Harris learned her landlord wouldn’t be able to boot her out if she entered bankruptcy. Plus, it would let her wipe away thousands of dollars of medical debt accumulated during the years she had little to no insurance and reset a credit history marred when a relative opened accounts in her name.

Attracted by the promise of a fresh start, Harris filed for bankruptcy in September.

While this saved the couple from immediate eviction, Harris didn’t realize most local property management firms have policies against renting to people who’ve filed for bankruptcy. (Eight of the 10 leasing agents contacted by MLK50: Justice Through Journalism said applicants must have had their bankruptcies discharged at least two years before applying.)

Since the pandemic began, bankruptcies have become less common across the country, thanks to a growing economy and increased federal assistance to needy families. Still, Shelby County leads the nation in personal bankruptcy filings per person, with a rate five times higher than the national average. And because of housing shortages across the country, fewer and fewer apartment complexes are willing to look past prior bankruptcies or evictions, Cadiz said. When property managers have no issue renting empty rooms, they have no reason to take risks on tenants such as Harris.

“They can choose someone with no evictions and a great credit score,” Cadiz said. “These people that don’t have that are out of the picture.”

Right after Harris filed for bankruptcy, she and Scott began looking for another home. But in the seven months between when Harris filed for bankruptcy and their lease ended, they’d spent about $900 in application fees at more than 15 rentals and still hadn’t found anything.

Finally forced out of their home, the pair moved into Extended Stay America in East Memphis in May 2021.

“Why is it that someone filing a bankruptcy (means) you can’t live nowhere?” Harris said. “(When I filed), I didn’t know I was just supposed to be homeless because I got a bankruptcy.”

Forming a community

While living in the extended stay, Harris and Scott continued to look for a home, but also formed a community.

Harris made friends with the housekeeper, the front desk workers and fellow residents. She cooked healthy meals for Mr. Williams, who was used to a diet of McDonald’s but was fighting diabetes, and for Mr. John, who taught at LeMoyne-Owen College.

“She’s an amazing person … (and) she always paid her weekly balance on time,” said Samantha Cowan, a former front desk worker.

Though Scott had landed a relatively high-paying job setting up power equipment for events and Harris was working part-time, the couple had difficulty keeping up with their other bills while paying the hotel $500 per week. A few months after moving in, Scott filed his own bankruptcy to lower his debt payments.

But throughout the second half of 2021, they were still hopeful they’d find an apartment soon.Those hopes faded the week of Christmas. Water started seeping through the floorboards in their room, so Harris demanded a different one. The hotel manager showed her another, smaller room that smelled awful. Standing up for herself, as always, Harris said she needed something better, and the manager walked to her office.

A little while later, Harris said she was summoned to the office and given a choice: Accept the new room or get out by 3 p.m. Harris agreed to move and picked up her husband from work, so he could move their things. But she also called the corporate office to complain. She then left to pick up some Instacart orders.

While driving in Cordova, she received a call from her husband. Police had arrived at the hotel and told him they had to leave. It didn’t matter that they had already paid for the rest of the week. It didn’t matter that they had lived there seven months or had nowhere else to go. The cops told Scott – falsely, as it turns out – that the hotel was legally allowed to throw them out for any reason.

Under Tennessee law, hotel residents must be treated as tenants once they’ve lived there for 30 days, according to West Tennessee Legal Services managing attorney Vanessa Bullock. That means hotel managers must get an eviction from a judge before showing someone the door.

Neither the Memphis Police Department nor Extended Stay America responded to repeated requests for comment about Harris’ removal.

Malik Watkins, a public service associate at the University of Georgia and one of the authors of the 2019 study, said hotel residents rarely receive the same rights as renters, partially because they’re largely ignored by both academics and politicians. His was one of just a few studies MLK50 found while researching this article.

“There’s a chasm when we look at housing policy (for hotel residents),” he said. “It’s a severe blind spot. … A lot of folks in local governments don’t even know it’s a problem. It’s not even on their radar.”

With little data available, it’s difficult to say how many Memphians are living in hotels. According to The Highland Group, there are about 2,200 occupied extended-stay hotel rooms in the Memphis area. Of those, about half are likely rented to long-term residents, according to Highland Group partner Mark Skinner. However, far more Memphians are living in cheap hotels and motels across the city that don’t include the kitchenettes required to count as extended-stay properties — including one of the hotels Harris and Scott lived in last year.

Even if politicians start paying attention, cops follow the law, and residents learn their rights, Watkins said, it will be tough for tenants to stand up for themselves when a hotel manager tells them they have to leave.

“There’s a difference between knowing your rights and being able to enforce them,” he said. “Are they supposed to leave their stuff sitting outside the unit and go call legal aid? … The practicality is they need to go find a place to stay.”

Harris and Scott couldn’t find a place the night they were kicked out. Having just spent $200 on groceries for Christmas dinner, they couldn’t afford most of the hotels they looked at. When they arrived at a cheap hotel in Cordova, it was full.

Life 'on the run'

In April 2022, while Harris and Scott were still staying in hotel rooms across the county, her doctor diagnosed her with triple-negative breast cancer.

By summer, Harris’ hair was falling out, her fingernails were curling up, and her toes were turning black from the chemotherapy.

Despite the extreme pain and exhaustion, Harris said seeing her reflection in the hotel room mirror was the hardest.

“All my hair is gone. … It’s horrible,” she said. “I’ve been wearing my hair long all my life — nice and long and thick.”

This mental battle compounded the stress from living in hotels, worrying about the viruses other guests might carry and never knowing when another manager may uproot her life.

Anxiety is the norm for long-term hotel residents, according to a 2010 study published in the Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare.

“(Residents) experienced an unrelenting emotional struggle with their inability to get out of this temporary housing solution,” the study says. “They feel trapped, boxed-in, and unable to escape the realities of their financial situations.”

These financial struggles often occur despite steady employment. Almost 70% of households living in hotels have at least one member with a full-time job, according to Watkins’ study. Scott, for instance, worked full-time throughout the couple’s hotel stays. Though he left his power equipment job when Harris was diagnosed so he wouldn’t have to travel as much, he quickly found work at a local railyard.

Many of these families could easily be paying rent at apartment complexes — if they weren’t constrained by an eviction, bankruptcy or apartments’ requirements to pay first and last month’s rent when moving in, Watkins and his colleagues found. If given a chance at an apartment, his study found, almost 80% said they wouldn’t need long-term financial support to keep it.

To give more families that chance, Watkins said cities and nonprofits should focus on “the root issue” of building more affordable housing.

The City of Memphis recently included $5 million in its budget for affordable housing, but the city has about 35,000 fewer affordable housing units than it needs, given its number of low-income residents, according to a 2023 analysis by the National Low Income Housing Coalition. Faced with this reality, national experts say Shelby County elected officials must make it easier to build rentals. Currently, housing developers here run up against some of the most exclusionary zoning rules in the country, which don’t allow apartments to be built in most parts of town.

Occupancy in affordable extended-stay hotels is intertwined with the price of apartments nearby, Skinner said. If more apartments are built, causing local rental rates to fall, fewer people would live in cheap hotels.

While not every apartment is better than every hotel room, Harris said having a decent apartment of her own during chemotherapy would have made a huge difference.

“(In hotels), you always feel like you’re on the run. You don’t feel settled,” Harris said. “I don’t think I’ll ever be comfortable staying at a hotel.”

The one time Harris was truly able to relax in 2022 came in late September. In between “red devil” treatments, she and Scott visited Gatlinburg with her cousin from Atlanta and friends from Chicago. On the porch of their cabin, she and her cousin sat on rocking chairs facing the woods for hours upon hours.

It was the opposite of hotel life.

“It was just comfy and cozy,” Harris said. “There was a warm feeling. And I got to rest.”

A crushing blow

In December, the same month she completed chemotherapy, Harris finally found a place willing to take a chance on her and Scott — the Almadura Apartments.

The Almadura is located in a low-crime part of Midtown and costs much less than the hotel they were living in. It seemed like a great deal.

So the couple signed a lease, not having seen the recent TV news story about the building’s falling bricks and other safety risks.

It didn’t take long for the Almadura to take its toll on them. Cockroaches became frequent guests. And black mold began to abound beneath their sink, causing Harris to have severe coughing attacks. Her doctor prescribed antibiotics but urged her to move somewhere safer while she received her immunotherapy treatments. Gynecologist Sanjeev Kumar, who owns the building, did not respond to requests for comment for this article.

The couple kept searching for a better home — until the afternoon of June 15.

Scott had stopped at the liquor store to pick something up for Father’s Day. Since he knew it’d be a quick stop, and their car wouldn’t start without being jumped, he decided to leave it running.

Someone stole it while he was on his way into the store.

Since that day, Scott hasn’t been able to get to work. He’s searching for employment within walking distance but hasn’t found anything. Even if he finds a job, he doubts it will pay nearly what the railyard did — which already wasn’t enough to cover their rent, his debt payments and Harris’ medical bills.

Harris started a GoFundMe, but it’s only raised $75.

If this had happened two years ago — before the hotel payments or cancer treatments — the couple probably would’ve been alright. Now, it’s a crushing blow.

Less than two weeks after the theft, the couple received notice that their landlord had filed an eviction. They had fallen behind on rent long ago but had hoped to stay in the Almadura until they found a viable alternative.

Because of their recent bankruptcies, they can’t use that system to save them this time.

At their first eviction hearing, they were granted a two-week delay, but they’ll likely be forced out of the Almadura by the end of July. They’re desperately searching for a way to avoid homelessness.

But they haven’t found one.

Jacob Steimer is a corps member with Report for America, a national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms. Email him at Jacob.Steimer@mlk50.com. MLK50: Justice Through Journalism is a nonprofit newsroom focused on poverty, power and policy in Memphis.

This article originally appeared on Memphis Commercial Appeal: How one Memphis couple is stuck between a home and homelessness